The world in 2026: ten issues that will shape the international agenda

Text finalised on December 15, 2025. This Nota Internacional is the result of collective reflection on the part of the CIDOB research team. Coordinated and edited by Carme Colomina, with contributions from Inés Arco, Samuele C. Abrami, Mariano Aguirre, Anna Ayuso, Jordi Bacaria, Pol Bargués, Javier Borràs, Moussa Bourekba, Víctor Burguete, Anna Busquets, Carmen Claudín, Lola Cutillas, Francesc Fàbregues, Oriol Farrés, Victoria Frois, Marta Galceran, Blanca Garcés, Patrícia Garcia-Duran, Seán Golden, Rafael Grasa, Francesca Lupi, Josep M. Lloveras, Bet Mañé, Ricardo Martinez, Esther Masclans, Oscar Mateos, Matthew McLaughlan, Pol Morillas, Francesco Pasetti, Lucía Pradel, Roberto Ortiz de Zárate, Héctor Sánchez, Antoni Segura, Laia Tarragona.

2026 will be a year of global readjustment. Trumpism has marked the beginning of a new era in the instrumentalization of economic and technological coercion.

The new year will test the ability to adapt in order to deal with the brutality in geopolitics: who comes out on top; who is capable of finding their place or even circumstances to impact on a seemingly chaotic order; who resists; and who feels overwhelmed, lacking the tools or leadership to cope with the changes.

In a world driven by transactionalism and interests, peace has become an asset with economic returns. The impunity of military interventionism is growing, as is the privatization of the benefits of a “crony diplomacy” that seeks to monetize peace processes.

In 2026, technological and military rearmament will intensify. But so will the sense of fatigue in the face of growing economic disparity and the disconnect between the priorities of the geopolitical agenda and the discontent of citizens.

2026 will be a year of global readjustment, of adapting for the sake of survival. The world is realigning. The new rules of the game are clear. Trumpism has ushered in a new era in the use of economic and technological coercion, and now we shall see who is better adapted in a year that looks set to embody the aphorism that might makes right. In the midst of the tariff aftermath, of expansionist interventionism and transactionalism, we will see an acceleration of the global reconfiguration of trade, financial and geopolitical connections.

2026 will test the guardrails and tools for dealing with the brutality in geopolitics. Competition for resources is heating up. That is why, beyond the long line of countries waiting to sign their own bilateral trade deals with Trump, there is an urgent need to seek alternative trade relations to the United States. From China’s efforts to project stability and expand markets, to European Union (EU) vassalage to Trump, or the new geopolitical spaces taking shape in the Global South, international relations are shifting. It is not only about winners and losers. There are also the opportunists, who have hit on a way to turn the reinstatement of imperialist agendas and doctrines to their advantage, and those acting from an unapologetic pragmatism, enabling them to secure a place—or even seize openings to exert influence—within a seemingly chaotic order; and then there are the resistant, who are driving protest movements or creating spaces that go against the tide; or the overwhelmed, feeling lost in transition, floundering in the wake of changes they lack the tools or the leadership to cope with. For some countries, 2026 could also be a year of “polytunity”. And not just China, which is clinging to the reinforcement of its export market to try to maintain economic growth, but also the Gulf states, with their amplified diplomatic and technological prominence, or India, as demonstrated by its transactional approach to Beijing or Moscow. For other actors, like the EU, this volatility has prompted them to cling to the goal of defence as a key vector of their policies, though with limited tangible outcomes.

But how to build an order without trust? As the technology of conflicts changes, and the big powers tear down the frameworks of governance and international law, the risk of opportunistic attacks, or even miscalculations, only increases. Strategic restraint—designed to limit uses and stockpiles to prevent military escalation—has collapsed. Political violence exceeded 550 daily incidents in 2025, and air and drone attacks reached an all-time high, as did defence spending to sustain them. 2026 will begin with a ‘new normal’ defined by high levels of violence.

The winners

1. Interventionism with impunity

As 2025 comes to a close there is a military build-up in the Caribbean unparalleled in recent decades. The world’s biggest aircraft carrier, a nuclear submarine, F-35 fighter jets and more warships form part of the US deployment in the region. The Trump administration has launched extrajudicial military attacks against alleged drug-trafficking boats in the Caribbean and the Pacific; it has threatened to intervene militarily in Mexico and Colombia, as well as seize control of the Panama Canal; and it has put a price on the head of the Venezuelan leader, Nicolás Maduro. Its threats have reached as far as Nigeria, a country it accuses of religious violence.

It is not just another episode of “gunboat diplomacy”. Trump epitomises the rising tide of states that are operating outside the law. With the breakdown of multilateralism, impunity is taking root. And, in violation of international law, spheres of influence are being restored through the barrel of a gun, as in Ukraine, Gaza or the West Bank. Early in the year, The New York Post coined the concept of the “Donroe Doctrine”, Trump’s version of a 19th century policy with which in 1823 the then president, James Monroe, strived to prevent other powers from encroaching on the American hemisphere. Now it’s official: the Donroe Doctrine, dubbed a “‘Trump Corollary’ to the Monroe Doctrine”, has been enshrined in the National Security Strategy 2025, which will define the next three years of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Two conflicts could deepen this legal black hole in 2026: one is the potential US attack on Venezuela; the other, the possible resumption of last summer’s inconclusive war between Israel and Iran, along with a renewed Israeli offensive against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Impunity has turned military interventionism into just another tool available to governments or international actors ready to make use of an increasingly deregulated violence. It is not a means that is exclusive to the major powers. Ever more countries are tempted to make gains by force. 2025 left us a series of sudden outbreaks of conflict, limited in time and territory, and with uncertain goals, but which led to a brief military escalation and a hasty and fragile ceasefire. The offensive by the Rwanda-backed M23 militias against the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in January; the escalation between India and Pakistan following the Pahalgam attack in the region of Kashmir in April; the week-long round of tit-for-tat strikes by Pakistan and Afghanistan in October; or the border conflict between Cambodia and Thailand that reignited in December are multiple examples of these border clashes that flare up and then die down over a short period of time. These tensions do not disappear altogether, however. Not even with the mediationof Donald Trump.

In 2026, similar episodes could be replicated across the globe. In Africa, the increasingly belligerent war of words between Ethiopia and Eritrea – over the former’s demand for an outlet to the Red Sea and accusations of interference and occupation against the latter – has reignited concerns of a fresh conflict between the two countries. Addis Abeba, moreover, is also locked in escalating tension with Cairo following the opening of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a tussle that is capable of upsetting dynamics even in other countries such as Somalia. In Asia, the deteriorating conditions of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh – who face an increasingly difficult situation owing to international neglect of the crisis – has boosted the recruitment of refugees into Rohingya armed groups eager to face off with the Arakan Army in Rakhine State (Myanmar), which is capable of destabilising the border region. In 2026, armed actors around the world will be even more willing to use force and openly disregard the consequences.

2. Privatisation of peace

2026 will start with the future of Ukraine on the negotiating table and a peace proposal cooked up initially between the personal envoys of the White House and the Kremlin. A Trump peace is built through business. It is not about settling historic grievances, but about applying a business mindset to incentivise a ceasefire that pays immediate dividends. His rhetoric of “peacemaker in chief” has yet to secure him his coveted Nobel Peace Prize, but it has stuffed the pockets of his inner circle.

With multilateralism in crisis, figures such as Trump, Erdogan or Xi Jinping, and countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates have claimed the role of new power brokers. The temptation to reduce peace negotiations to a mere conflict of interest exercise is clear, and it often not about the interests of the warring parties, rather those of the negotiator. Traditional diplomacy has been replaced by deals between magnates. It is “crony diplomacy” in the service of private gain. An early indication came with the recently elected Trump’s bizarre idea of buying Greenland, a proposal that revealed his take on foreign policy that sees diplomacy as a transaction and sovereignty as a negotiable property. In a world of transactionalism and interests, peace has become an asset with economic returns.

From the “peace dividend” popularised by the West at the end of the Cold War to support a military drawdown which offered gains in economic growth and resources for social welfare, we are now treading the opposite path, and quickly. Not only because of the rearmament we are seeing, but also because the transactionalism that pervades the recently negotiated agreements first and foremost benefits private interests and autocratic regimes. But who is making money from peace?

Following the fragile agreement signed in June between Rwanda and the DRC in Washington, the United States announced that it had obtained “a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo.” Since then, a series of companies in the orbit of Donald Trump – or the tech circle that has backed him – have signed contracts in the region, including: KoBold Metals, a company financed by Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates that engages in data collection and research into critical minerals using artificial intelligence (AI); Ballard Partners, a consultancy firm linked to the Trump family; or Apple (while the company strongly disputes that its supply chain has anything to do with the conflict in the DRC, in January 2025 an investigation was opened in Belgium into the tech giant’s subsidiaries over the alleged use of “conflict minerals” in their supply chain). At the same time, Qatar – which also facilitated the framework deal in Doha – has promised $21bn in investment for the region in sectors such as agriculture, mining or hydrocarbons.

Another rapprochement, confirmed between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the White House on August 8, also translated into a trade deal. The agreement provides for the entry of US firms with a 99-year lease to oversee the creation and operation of a rail corridor, considered potentially lucrative, which will cross Armenian territory along its entire border with Iran. It will be called the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). Meanwhile, Azerbaijan and ExxonMobil also signed a memorandum of understanding that cements the US oil company’s position as a key player in the region’s economic future. The final peace agreement, however, remains pending and is set to be signed in 2026.

In Gaza, multiple actors are gearing up for a reconstruction that will require approximately $70bn, according to the United Nations. The adoption of Resolution 2803 (2025) by the Security Council – which legitimises Trump’s plan – solidifies the future of a Gaza without Palestinians, who will face risks of partition and expulsion. In 2026, barring a flare-up of the conflict, we will see the emergence of an apparent contest among the various reconstruction plans, though it is the White House’s leaked proposal that has every chance of winning. According to Trump, this plan envisages generating some $185bn profit in a decade for US firms – including Elon Musk’s Tesla, Amazon Web Services, or Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – but also for businesses from Europe, the Gulf states, Argentina or Turkey. There have been initiatives from the Palestinians themselves, the Arab countries or Israel too.

It is, in fact, the great fortunes of the Persian Gulf who are carving out a niche for themselves as the new mediators in the search for a strategic peace and with regional and global interests. In 2025, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had a hand in negotiations between Ukraine and Russia, Pakistan and Afghanistan, Azerbaijan and Armenia, the DRC and M23, and Russia and the United States, as well as in Gaza, in some cases facilitating US efforts. In 2026, the quartet formed by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and the United States will try to add Sudan to the list of territories brought to peace by Trump, bearing mind that the three Arab countries have backed different factions, with Abu Dhabi benefiting from the gold mining operations controlled by the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces.

While these new players deploy their mediation skills, bridging the necessity of halting the violence and the obscenity of the economic returns from their actions, the machinery of international diplomacy, from the United Nations to foreign aid, is increasingly impacted by funding cuts. Although the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund celebrated hitting the $1bn milestone in November 2025, its activity next year will be blunted by a $500m shortfall that limits its ability to meet growing international demand. The budget for peacekeeping missions also continues to shrink.

3. More weapons, troops and military AI

While cooperation is being scaled back, the defence sector is booming. Technological rearmament and troop numbers will be stepped up in 2026.

According to the latest SIPRI report, the revenue from arms sales hit a total of $679bn in 2024, the highest figure since 1989. The main beneficiaries were arms-producing companies in the United States (49.19% of global earnings) and Europe (22.24% of total revenue). Yet these figures do not include the emergence of new military industries, like investment in the development of AI applications for decision-making and target recognition, processes that do not always have a human in the loop. According to EuroDev projections, military spending on AI could exceed $30bn by 2028, with the United States and China leading the way .

Then there is investment in autonomous systems such as drones, capable of launching an attack independently. In fact, in 2025 there was a boom in the use of drones in conflict situations beyond Ukraine and Gaza: from episodes of criminal violence in Haiti or Colombia to instances of hybrid destabilisation in Europe. In Asia, for example, they are redefining the military escalation between Pakistan and India; drones are a constant presence in the South China Sea; and they are crucial to the course of the civil war in Myanmar. The automation of remote-controlled violence is changing the nature of warfare, fostering a new drone race. According to figures from the Atlantic Council, China controls around 80% of the global drone market, both in terms of final production and the manufacture of components. In addition, according to the initial recommendations for the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030), the “low-altitude economy”, linked to the application and marketing of drones in different sectors, will be a priority in the coming years.

The United States too, with its Replicator programme (2023–2025), is investing in aerial, maritime and land drones; they must be low-cost and replicable, and operate as single-use, autonomous apparatus completely controlled by AI. In December 2025, the Pentagon unveiled the Drone Dominance Program, which provides for the development and purchase of 200,000 units by 2027. Norway and Ukraine, meanwhile, will begin joint drone production as of 2026. And the recently announced European Drone Defence Initiative (EDDI), aimed at developing an interoperable system for countering and deploying drones, hopes to reach initial operational capacity by the end of 2026 and be fully functional in 2027. All this is happening in a race against the clock, following the Pentagon’s new deadline for its European partners to take over most of NATO’s conventional defence capabilities by 2027.

Defence will be key for the EU in 2026. With the launch of its defence readiness plan, the first six months of year will see the kick-off of two of the four flagship projects: the aforementioned European Drone Defence Initiative (EDDI) and the establishment of the Eastern Flank Watch. It also plans to unlock joint funding from the European Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) or to conduct a review of the industrial capacity required to ensure that 40% of European defence contracts occur between member states by 2027.

But this race also means an increase in forces, with the controversial expansion of military service in the EU. National service is already mandatory in Austria, Sweden, the Baltic countries, Finland, Cyprus, Greece and Denmark (which in 2026 will expand the voluntary service for women). As of January 2026, Croatia will reintroduce compulsory military service, 18 years after scrapping it. Germany, meanwhile, will opt for a voluntary system, but the law passed by the Bundestag has already triggered protests. Belgium and Romania too are introducing voluntary military service, while in the summer of 2026 France will bring in its own form of paid voluntary military training lasting ten months, aimed at 18- to 19-year-olds. The same trend can be seen outside Europe: Cambodia will start compulsory military conscription for the first time; Jordan will reinstate it after 34 years; and in Latin America, Argentina will offer a voluntary scheme and Mexico will extend its duration.

All this process of militarisation also involves a profound change in the relationship between the market and the armed forces. Today, major defence tech companies retain exclusive control over the data-based systems that are crucial for military operations. Their technologies are not simply transferred to the state, rather it is the companies that integrate into the war decision-making architecture. Tech players like the US company Palantir, for example, are embedded in Ukraine’s war economy. And it is not the only one. Under the banner of “patriotic tech”, a series of companies and investors are “privatising the sovereignty” of the United States, whether it is through donations to the Department of Defense to maintain the salaries of military personnel during the federal government shutdown; via the promotion of the public acquisition of stakes in defence companies; or the announcement of over $10bn investment in defence by JP Morgan Chase. The symbiosis between capital, the state and the armed forces will continue to take root in the United States in 2026.

And all this is happening in a context characterised by the absence of new arms control treaties – for example, to mitigate the risks associated with the militarisation of outer space or the growing automation of weapons systems. Meanwhile, existing treaties, such as those covering nuclear weapons or landmines, are crumbling, with countries withdrawing and failure to agree on new terms. It remains to be seen whether Vladimir Putin maintains his proposal of a one-year extension to the New START treaty as of February 5, 2026. Although the latest data fuel the fear of a new nuclear arms race led by Washington and Moscow, it is Beijing that it is increasing its capabilities quicker than everyone else. In this new arms and tech showdown, the absence of international rules, regulations and standards paves the way for increasingly unchecked competition and proliferation.

The opportunists

4. A global race to diversify alliances

The cards are on the table now in 2026. Trump has signalled the dawn of a new era in the instrumentalisation of economic and technological coercion. Trade and political uncertainty are the new normal. But the impact of the US new economic order, with a slowdown of global trade, will start to show in the coming months. The World Trade Organization (WTO) reckons the percentage of global trade that respects its rules has shrunk to 74%. What’s more, according to its calculations, global trade volume will grow by just 0.5% in 2026, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is anticipating global economic growth of 3.1%. The system held up in 2025 thanks to massive imports of products ahead of Trump’s tariffs, the restraint shown by countries when responding to these measures, increased demand for AI-related products, and a growth in trade among the rest of the world. But this buffer effect is wearing off and the impact of the tariffs will be visible in prices, investment and consumption, coinciding with the first full year of this surge in protectionism.

In 2026, we shall see whether the new trade deals with countries and regional blocs, as well as the truce struck in Busan in October 2025 between the US president and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, hold up or collapse with a fresh round of tariffs. For the moment, Trump has secured the resumption of China’s purchases of US soybeans and a pause on some rare earth export controls imposed by Beijing – restrictions that could have a major impact on Europe in 2026. Although Trump, on the face of it, will prioritise stability until his trip to China scheduled for April this year, his trade policy is pending a United States Supreme Court decision on the legality of the “reciprocal” tariffs and their potential inflationary impact on US families. And all in an election year.

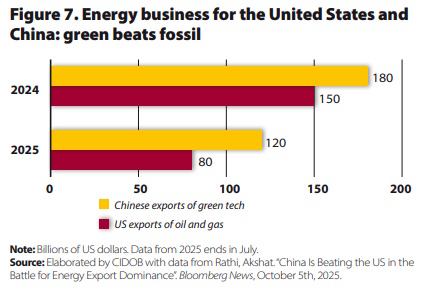

Paradoxically, China will end 2025 with a record trade surplus thanks to exports of vehicles and clean energy technology. While the United States is closing its doors, the rest of the world – especially the Global South – is the major recipient of Chinese exports, despite the introduction of some trade restrictions on the Asian giant. Yet uncertainties await it in 2026. Beijing fears the impact of lower external demand and the possibility of new protectionist measures in other parts of the world, which could try to limit the effects of the rerouting of Chinese goods and safeguard the future of local industries in those markets. Consequently, China must contend with a slowdown of its main growth engine at present – trade – while it faces considerable challenges at home: domestic consumption is not quite taking off, youth unemployment is close to 20% and the phenomenon of “involution” (内卷neijuan) – overinvestment and cut-throat competition among domestic businesses, sending prices and companies’ profits into free fall – will ramp up deflationary pressure. Even so, the prospects of a change of tack in the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030) to be adopted in March 2026, are close to zero: the priority will continue to be technological self-sufficiency, industrial modernisation and that elusive increase in domestic consumption.

The rest of the world, faced with Trump’s unpredictability and Chinese competition, will seek alternative trade relations. It is not just a matter of diversifying. Rather, a genuine scramble to secure stable and lasting agreements is underway. Moreover, the US administration’s policy of maintaining a weak dollar and low oil prices are driving growth in emerging countries. But who are the main players in this new hyperactivity?

India is currently engaged in trade negotiations with more than 50 countries. Its news websites are filled with optimism over new deals with Canada, New Zealand or Oman in 2026. The jewel in the crown, however, would be the signing of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between India and the EU during the bilateral summit in January 2026. While sticking points remain over key issues such as agriculture or the protection of pharmaceutical patents, in the final weeks of 2025 the conclusion of these negotiations could also be one of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s first victories of her second term. She has found a new ally of convenience in President Narendra Modi, despite the latter’s theatrical entente with Vladimir Putin. At the same time, Indian diplomats continue to negotiate a deal with the Trump administration to reduce the tariffs of around 50% in force between the two countries – the highest in the world in November 2025 – and renegotiate the respective agreements with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

ASEAN, for its part, is in the final stages of the negotiation of a Digital Economy Framework Agreement among its members, which will be the first regional pact focusing exclusively on the digital economy. It is expected to take effect in 2026 to boost integration in the face of external threats. But as well as negotiations as an organisation with India or Canada, the member states are also taking positions individually. The Philippines hopes to close four agreements in 2026: with Canada, the United Arab Emirates, Chile and the EU. While, Malaysia and Thailand are negotiating separately with Brussels to seal agreements in 2026 and Indonesia is pending ratification. In addition, the staging this year of the summits of the BRICS+ group (Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and South Africa, plus Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ethiopia and Iran) in India and of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in Vietnam will cement the sense of Asia’s centrality in this support of free trade.

Nor is Brussels standing still. It is expected to reach a decision on the final signing of the deal with Mercosur in December 2025, even though opposition from Poland and France is putting it at risk. The outcome will be crucial for its credibility vis-à-vis the parallel negotiations with India and ASEAN, as it adopts a harder trade stance on China and debates whether to tighten regulation of investment from that country.

Trust – or the lack of it – will also play a fundamental role in the review of the first six years of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 2020. During the consultations and negotiations, the three parties must assess its operability, whether any update is necessary and whether to agree to extend it for another 16 years. While United States tariffs on Canada and Mexico have increased suspicion in sectors such as the automotive industry, negotiations are expected to focus on US concessions on non-trade issues like migration or updating chapters related to value chain resilience and rare earths.

Moscow, too, is taking part in this dash to diversify trade alliances. The Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), which includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan as well as Russia, could seal its first free trade agreement with a third country, if the deal reached with Mongolia in June 2025 is ratified. And it is not the only one. November 2025 saw the end of the first round of negotiations with India, a country that, despite being targeted for additional sanctions over its energy business with Russia, has no plans to shut the door on its longstanding ally.

5. Tech bubble slowdown?

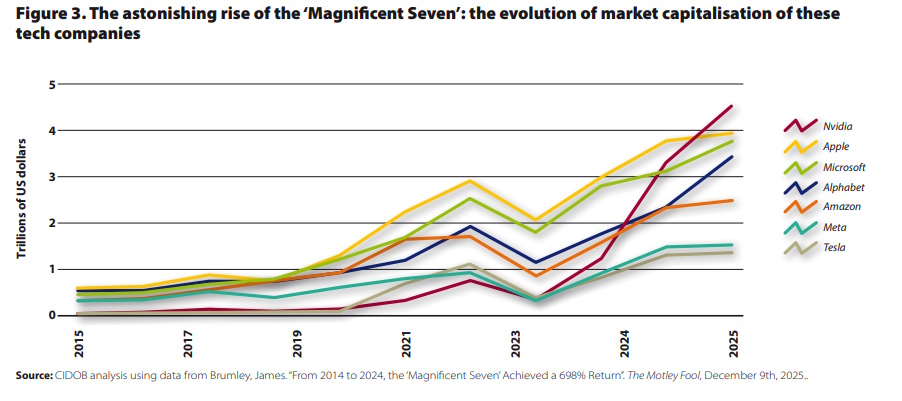

The value of AI tech firms has soared in recent months. The “Magnificent Seven” (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla) account for one-third of the S&P 500, the index that gathers the 500 biggest companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. The market capitalisation of the big four alone (Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple and Alphabet/Google) is equivalent to 50% of US GDP in 2025; some have increased their market value sixfold since 2014. This means that the growth of the American economy depends dangerously on investment in AI infrastructure: from the construction, for example, of costly datacentres to chip manufacture and energy generation. The engine driving the economy, however, should be more versatile, as US capital is highly concentrated around Silicon Valley. Accordingly, the perception that the US economy is for the most part in the hands of just seven companies has begun to create a certain nervousness.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development(OECD), the huge investment in AI has helped maintain a certain economic resilience to tariff pressure. But concerns are now centred on potential market corrections in the face of unfulfilled expectations. Where are the limits of the race to build AI infrastructure?

The question is also whether this sector can generate enough profit to warrant the massive investment it is administering. What’s more, capital flows in a loop around the tech companies, which is fuelling the idea of a bubble. They are all investing in one another, particularly around Nvidia, the maker of the chips that all these companies need. Nvidia grows in step with the contracts it signs with these tech giants, and in turn it invests in those same companies, its main customers. It is a self-perpetuating cycle, a house of cards that depends on the resistance of every one of its components. For all these fears, Nvidia’s numbers remain spectacular. The question is whether this level of euphoria is sustainable and what will happen if it stops. For the moment, in December 2025, Trump authorised Nvidia to export AI chips to China with a tariff of 25%. Faced with the dilemma of blocking the sale of technology to its rivals in the race between the two powers or not restricting Nvidia’s market or resources, which it needs to continue developing latest-generation chips, Washington has opted for the latter.

The idea is gaining traction that big tech’s hegemony has fuelled a “capitalism on steroids”. It is a major problem. If these billion-dollar investments slow down, the US economy and, therefore, the global economy will feel the impact in their growth. In addition, the mirror of the Chinese model, which is getting very good results with limited access to advanced chips, reveals the Achilles heel of tech development in the United States. Rather than pursue the invention of cutting-edge tech over the last few decades, the Asian giant has opted to scale up and bring existing technologies to the market efficiently. It is a direction it is also taking in the field of AI.

In this context, however, Silicon Valley is flexing it muscles worldwide. Concerted pressure from the big tech platforms alongside the Trump administration has put a dent in the EU’s regulatory framework. So much so that it is considering delaying the implementation of its rules on high-risk AI systems, scheduled for August 2026, to late 2027. It is one of the measures of the “digital omnibus” package proposed by the European Commission to lighten the regulatory load and increase competitiveness within the European economy, which has direct implications for the protection of users’ fundamental rights. Similarly, in December 2025 the EU’s executive branch presented a new economic security strategy in response to growing tech protectionism and to reduce dependencies on critical raw materials. It did so after a year marked by pressure from, among others, China, which imposed rare earth export controls and temporarily blocked shipments of automotive chips from the Dutch company Nexperia, a strategic link in the EU’s supply chain.

The Gulf states, meanwhile, continue to bank on AI as a means of safeguarding their wealth and global influence in a post-oil world. Countries such as Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates have sunk billions of dollars into positioning themselves as global AI infrastructure hubs, in many cases in partnership with firms from Silicon Valley. In doing so, they too are adding to the eye-watering investments inflating the bubble. In May 2025, the United Arab Emirates signed a deal worth billions with OpenAI to build one the world’s largest AI campuses. And in November, Microsoft became the first company under the Trump administration to be granted licences to export advanced Nvidia processors to the United Arab Emirates.

One of the greatest challenges for the Global South, however, is to generate its own data, which requires being able to digitalise them and ensure their quality. These processes take decades, though there are already some interesting attempts. In Latin America, for example, Latam-GPT includes not only web crawl data, but also new data obtained through the institutional alliances it has established with Chile’s National Centre for AI (CENIA). These initiatives are fundamental for strengthening digital sovereignty and developing technology that reflects global diversity.

All this tech development also means that the tension between profit concentration and the social costs has rocketed. In the United States, the tech sector accounts for over 10% of the energy consumption in several regions. AI has a direct impact on electricity prices. US households’ electricity bills are higher than ever, after 2025 saw the biggest price jump in nearly two years. And energy costs are expected to rise even higher in 2026.

Finally, digital opportunism is also fuelling the cryptocurrency industry, including companies linked to Donald Trump. In the broader crypto‑asset ecosystem, stablecoins are set to play a prominent role in 2026 following the legislative changes introduced by the new U.S. administration. The Trump administration aims to secure the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency through the expansion of this digital asset backed by U.S. deposits and debt. Riding this momentum, Europe will promote euro‑denominated stablecoins while inching forward with the digital euro. In the Global South, the BRICS countries will lead resistance to dollarization efforts by developing digital payment systems and alternative platforms.

The resistance

6. Gen Z, between expectations and reality

A tide of generational discontent is sweeping the globe, led by those born between the mid-1990s and 2010, approximately, at the turn of a millennium marked by a succession of crises. Gen Z has staged demonstration in several countries and continents to demand tangible changes in imperfect, corrupt and unequal political systems. In 2025, the discontent hit the streets of Nepal, Madagascar, Morocco or Peru, among others; and, more incipiently, in Indonesia and the Philippines. In Kenya or Serbia, the protests had begun in 2024. In Bangladesh too, where there were major waves of violence. And in Sri Lanka in 2022. These movements are scattered across space and time. The spark has been different in each country, but they all share a deep dissatisfaction and the sensation of living in a climate of violence: social violence, on account of injustices and corruption; environmental violence, because of resource deprivation and climate impacts; human violence, in the shape of rights violations and inequalities.

In Mexico, Gen Z rallied in November to vent its anger at corruption and narco violence that claims thousands of lives a year. In Peru in September, young people also protested against graft, the might of organised crime and the fragility of the institutions in a country that has had as many as seven presidents in ten years.

In Morocco, where one in three young people is unemployed, the cause of the common discontent is a development model that disregards social welfare in favour of huge investments in infrastructure. Calls for a reform of the education system and better public health care will also ring out in the upcoming legislative elections scheduled for summer 2026.

All these protests are a sign of the population’s growing impatience at the ever-widening gap between expectations and reality. The question is, then, whether 2026 will bring fresh sudden outbreaks, as already occurred in December in Bulgaria, where tens of thousands of people took to the streets to expose the government’s widespread corruption and its mafia-style connections, ultimately forcing the resignation of Prime Minister Rosen Zhelyazkov. While the trigger for the demonstrations was a controversial budget plan, which the government already withdrew, the unrest channeled indignation at state capture and the breakdown of public services such as health care, just weeks before Bulgaria’s official entry into the euro on January 1, 2026.

In some cases, the protests have already brought about political change. In Nepal, for instance, a young population frustrated by precarious economic conditions turned the ostentatious image of the children of Nepal’s political elites on social media into the spark that forced the prime minister’s resignation in September. An interim government has promised elections in March 2026. In Madagascar too, one of the poorest countries in the world where 50% of the population belongs to Gen Z and eight out of ten young people cannot make a decent living, the protests led to the downfall of the government and the army taking power for the next two years.

Bangladesh, meanwhile, will hold elections in February 2026, followed by Nepal, Morocco and Peru. The results of the votes will invite reflection on the prospects for change and the true impact of these protests in their capacity to formulate alternative policies. In cases like Serbia or Bangladesh, young people are creating their own political movements, though not always with the idea of taking part in elections in mind. In Nepal, on the other hand, Gen Z is favouring political outsiders like the mayor of Kathmandu, Balendra Shah, a controversial politician with an authoritarian tone.

We are receiving a global warning from a digital generation who has grown up in times of accelerating change and uncertainty about the future. Growing socioeconomic disparity and the idea of relative deprivation, hyperconnectivity and the sense of vertigo caused by globalisation and technological transformation are part of young people’s collective experience. As is detachment from traditional political parties. Social media, on the other hand, has allowed them to share solidarity, tactics and cultural references.

In 2026, then, we shall see whether these spaces of resistance or contestation make the leap to the ballot box, as already occurred in 2025 with the new mayor of New York, Zohran Mamdani, a young Muslim representing the far left of the Democratic Party. He has become the symbol of an unexpected counteroffensive on the part the Democrats, who had lost all sense of direction in the United States.

In Europe, the parliamentary elections in Hungary, scheduled for April 2026, promise to be the most significant in decades. After 15 straight years of government by the ultraconservative Viktor Orbán and dominance of his Fidesz-KDNP coalition, the political landscape is shifting. Against a backdrop of a decline in living standards, widespread corruption and poor public services, Orban’s grip on power is slipping. The latest polls show the opposition party TISZA, led by the conservative MEP Péter Magyar, who broke away from Fidesz, is in the lead with 42.8% of the vote, ahead of Fidesz-KDNP on 36.9%.

Lastly, Istanbul is also a city of resistance to the autocratic power of Recep Tayyip Erdogan. While Turkey prepares for a diplomatically intense 2026, with the organisation of the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP31), the NATO meeting, and the summit of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS), the judicial persecution of the current mayor of Istanbul, the social democrat Ekrem Imamoglu, has redoubled. Erdogan’s main rival faces a prosecutor’s office request of 2,352 years in prison for an alleged corruption scheme. His arrest in March 2025 unleashed a wave of anti-government protests. It remains to be seen whether Turkish young people, who have repeatedly been the drivers of resistance to Erdogan, will take to the streets again in the coming months.

7. The socioeconomics of fear

Global economic growth showed signs of remarkable resilience in 2025, despite the Trump whirlwind. However, projections point to stagnation, and fear and pessimism will shape economic and social agendas. Against this backdrop, 2026 will test the resistance of societies under the weight of uncertainty and the erosion of well-being.

In the European Union, the weekly shop costs 34% more than it did in 2019, according to European Central Bank (ECB) calculations, plus the fact that food prices have an outsize influence on the perception of inflation. On average, Europeans devote 20% of their budget to food, more than double what they spend on other items such as energy.

Public debt is also climbing ever higher, and it affects the biggest and richest countries. Fiscal problems in France and the United Kingdom will remain a cause of concern in 2026, especially given the pressure to continue hiking defence spending. In Germany too, Friedrich Merz’s government has lamented the ballooning cost of the country’s social welfare system and how it squeezes the state coffers, along with the billions of euros it will take to rearm the Bundeswehr. The priorities marked by the geopolitical agenda (like defence, the war in Ukraine or trade deals) do not speak to people’s everyday lives, and discontent is reflected at the ballot box.

Housing, transformed into a black hole that swallows income improvements, had an impact on elections in the Netherlands, Canada or Australia in 2025, generally fuelling the results of the far right, but also sweeping Zohran Mamdani to victory in the New York mayoral race. The Democrat candidate mobilised new voters with a programme that spoke directly to their concerns. According to a recent poll carried out in American cities, most mayors believe that housing affordability in their cities will only get worse in 2026. The housing crisis also sparked protests in Mexico against gentrification and rising prices, which have tripled in the last decade.

In the United States, the national debt hit $38tn in 2025, reporting the fastest growth to date outside of the COVID-19 pandemic. The fear that the debt will also fuel higher inflation and erode Americans’ purchasing power is beginning to take hold, as social and economic gloom sets in. The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index today is lower than in the period immediately after the financial crisis of 2008; lower even than in 1980, when unemployment in the United States topped 7% and inflation reached 14%. Today, joblessness has grown to 4.4%, while inflation has increased to 3%. But the figures fail to reflect the social malaise aggravated by announcements from major employers (Starbucks, Walmart, Amazon, Verizon, Meta, HP, Chevron or Exxon, to name just a few), who have joined in the job cuts. This pessimism affects both citizens who are not recouping purchasing power and big corporations that, in the face of Trump’s erratic policies and ongoing trade uncertainty, have yet to pass tariffs on to consumers but are turning instead to cost‑cutting measures. And the fact is that even if the US economy continues to grow at a steady pace in the next two years, the figures hide a considerable inequality and vulnerability lurking under the surface. Without investment in data centers and AI, the United States would have come close to a recession in 2025. It was in this context in December that Trump unveiled a $12bn aid package for US farmers who, despite having widely backed Trump in his return to power, have been hurt by the trade war with China.

Debt is devouring the revenues of a major part of the Global South too. According to IMF data, in 2025 47 countries allocated over 50% of their budget revenue to servicing the debt, and a further 75 countries devoted more than 33%. In Latin America and the Caribbean that means the worst level since records began. In total, 5.2 billion people worldwide live in countries where the debt commitment exceeds social spending. This rollback, moreover, coincides with major cuts in international aid decided in the Global North, whose effects will be felt more clearly in 2026. The World Inequality Report 2026 shows how the concentration of wealth is not only persistent, but it is also accelerating. In the first six months of 2025 alone, the wealth of Latin American billionaires grew 12 times faster than the regional GDP of 2024.

Lost in transition

8. European strategic disorientation

2026 could be a crucial year for the resilience of the European model, or the year it reaches its political limits in a European Union caught between internal fractures and external threats. The EU is increasingly disoriented in this global readjustment that has transformed “the grammar of commerce” based on a language the Europeans had completely mastered and on alliances that had guaranteed their geopolitical security. It is not just about the effects of Trumpism any more, or about diverging approaches to China, but an awareness of internal weakness, marked by the crisis of its traditional powerhouses, as well as the rise of new political majorities far removed from the conventional idea of integration that had steered the course of European construction.

In 2026, this strategically disoriented EU, grappling with the obstacles to boosting its strategic autonomy and overwhelmed by the use of economic force and the geopolitical disdain of its chief ally, must decide where its capitulation stops. Donald Trump’s National Security Strategy 2025, released in December, redoubles the challenge. For the first time, a US administration is openly stating that it wants to see the EU destroyed, setting itself the target to “correct” Europe’s political trajectory and foment “the growing influence of patriotic European parties”, “cultivating resistance” inside its member states. Trump, then, portrays himself as the all-powerful accelerator of the forces of disintegration eating away at the EU from within.

In 2026, then, the voices within calling for a firmer response to these threats will grow louder, but at the same time support will increase for Eurosceptic and far-right parties, which advance inexorably with each new election. We are in a Europe of fragile governments and majorities. In 2025, voters punished the parties in power, regardless of their political stripe, and the governing parties in Germany, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands lost the elections. The far right is shaping up to be the main beneficiary in voting intention for 2026. Alternative for Germany (AfD) leads the polls in a year when there will be regional votes in the Länder of Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Saxony-Anhalt, Mecklenburg and Berlin. AfD is expected to hit double figures in all of them, and in the two eastern states of Saxony and Mecklenburg the far right is within touching distance of an absolute majority in voting projections.

Similarly, the National Rally (RN), Marine Le Pen’s party, leads voting intention in France, and the Freedom Party (FPÖ) would score another victory in Austria. The far right could triumph in Romania and Latvia too. Reform UK, the party of Brexit ideologue Nigel Farage, was bolstered by the local elections held in 2025 in the United Kingdom and is already pressing for an early general election, scheduled for 2029. In March 2026, there will be local elections in France too, which will serve as a gauge of the countrywide support for the far right. The vote will be marked by security, local finances and housing. All against a backdrop of constant government crisis and civil unrest in the streets, which hasten the breakdown of a state skewered not just be Emmanuel Macron’s irreversible decline and the pressure of the soaring French public deficit, but also by the opportunity this disarray presents to the RN, which is already the biggest party in the French National Assembly.

Meanwhile, electoral exploitation of the immigration phenomenon is on the rise, and European unity revolves around tightening reception and border control policies. The EU agreed on a new Pact on Migration and Asylum in 2024, which will enter into force in mid-2026 and usher in quicker deportations, new and questionable designations of “safe countries”, return centres and a new Solidarity Fund, considered a key component of the deal. A hard line and the “illusion of control” prevail, even among governments and parties that once maintained liberal stances on this issue. The appearance of vigilante patrols on the “hunt for immigrants” in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Poland, Ireland and Spain warns of an increase in violence and a “growing internationalisation” of right-wing extremism.

The European Union faces its own trilemma: how to boost economic growth, rein in enormous public deficits and increase investment in defence without austerity whipping up support for far-right parties still further. This tension will intensify in 2026 due to the growing difficulties in financing Ukraine and the negotiations over the future budgetary framework for 2028–2034. That is why it is also likely that the EU will scale back its emphasis on economic security, because it implies taking measures to decouple from the United States that would impact the bloc’s growth. While a response cannot be ruled out, like the possible triggering of the EU’s anti-coercion instrument, 2025 already provided clear clues as to the extent of European resignation. In addition, pressure from the Trump administration over the bloc’s regulations has turned EU digital legislation into a battleground. In this light, Europe must also measure the risk of inaction and the impact of putting a brake on regulation, which is already claiming certain commitments on the green agenda.

9. The climate: a geopolitical casualty

If there is one space that reflects the current contradictions and political disorientation it is the climate agenda. 2025 is ending with all-time highs in the adoption of renewable energy – a growing trend year after year, led by Chinese investment inside and outside the country – but also with a fresh expansion of hydrocarbons and a new record in fossil fuel emissions. While the climate emergency discourse and the imperative of a green transition are taking root, geopolitical competition evidences the difficulty of fulfilling the climate commitments established internationally at the various COP meetings. As The New Yorker points out, 2025 has been considered “a low point in human inaction on climate change”.

The closure of COP30 in Belém (Brazil) without agreements on a fossil fuel phase-out and without financial support from the developed countries for the climate transition in the Global South revealed the current lack of consensus in multilateral climate governance, with and without Washington. In a year when the parties should have renewed their ambition regarding the Paris Agreement (COP21, 2015), only 122 countries submitted fresh plans. And according to Climate Watch data, the new contributions are not enough to keep global mean temperature below either 1.5°C or 2°C above pre-industrial levels. Not even the anticipated leadership from China and the European Union has been up to the task.

2026 will consolidate this shift in global priorities. The fortitude of the EU’s climate agenda is in doubt. On January 1, 2026, its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will take effect. But the “omnibus” package adopted in late October 2025 already saw to scaling back its ambition. Cloaked in a discourse of competitiveness and simplification, the EU has watered down private sector responsibility in sustainable development and in monitoring its economic activity. This measure adds to a list of previous backpedalling, like the pause on the anti-deforestation law or the extension of exemptions to pollution targets for the automotive industry. But there is particular concern over the review of part of the “Fit for 55” climate package scheduled for 2026, as it too could be watered down. So, despite having adopted a target to reduce between 66.25% and 72.5% of greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2035, these policies appear to go against it. Competition with China, moreover, has also prompted the EU to protect its share of the market from the investments of global competitors in green tech.

As of January 27, 2026, the United States’ second withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, announced after Donald Trump’s return to the White House, will also become effective. His campaign mantra of “drill, baby, drill” will translate into over 500m hectares of new oil explorations off US shores between now and 2031, and the opening of new coal mines inland, a policy he already put into operation in 2025. But this oil boom is not limited to the United States. Outside the Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OPEC), Brazil, Guyana and Argentina will lead the growth in oil production in 2026, with recent deposit discoveries leading Latin America to be considered “the new oil frontier”. Although Brazil’s president, Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, ended 2025 with an order to draw up a road map to move towards a model of reduced dependence on fossil fuels, it sits uncomfortably with the country’s place as the region’s biggest hydrocarbons producer. These increases in production only compound the sense of inaction marking the here and now worldwide. According to a study by the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), the fossil fuel production planned for 2030 will be over 110% higher than the level established to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

In 2026 we shall also see how new connectivity projects to link up with fossil fuel corridors gain ground. If the Gaza peace plan holds and reconstruction moves forward, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) aims to become an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), offering greater energy integration that includes the development of gas pipelines and new liquefied natural gas terminals to connect Saudi Arabia, Israel and various countries in southern Europe, such as Greece and Italy. At the heart of these efforts is Russia, too. Moscow is leading the operationalisation of the North-South Transport Corridor, which would connect India and Russia via the Caucasus and Central Asia. This corridor would also contribute to the new energy cooperation between Iran and Russia underway in 2025, a bid by both countries to secure a lifeline in the face of international sanctions. It remains to be seen whether the binding agreement signed between Russia and China will lead to the crystallisation of the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, with a target capacity of 50bn m3 of natural gas per year. It is still in limbo owing to Chinese reservations and key disagreements over issues such as the course of the route or the price of the gas. Competition for resources and fluid alignments are clear in the energy field.

Yet despite the backtracking led by the usual sceptics, there has been progress too. They may have been minor victories, but COP30 ended with the adoption of a just transition mechanism, a gender action plan and the pledge to triple finance for adaptation to climate change by 2035. In addition, in 2026 the world will cross the threshold of producing 20% of its electricity through renewable energy for the first time. The Global South, for example, which sees the green transition as a way to gain more autonomy from the fossil fuel markets, leads the development and adoption of green tech. China now earns more from its renewables exports than the United States does from hydrocarbons; and India is looking to become the second country in the world in terms of renewable deployment, also in a quest for energy independence through diversification. Thus, the fact that some countries remain at the forefront of the green agenda now owes less to the urgency of climate action than to pragmatism, self-sufficiency and new economic benefits in an uncertain geopolitical world.

10. Autocratisation of the United States

Despite its ubiquity throughout this Nota Internacional CIDOB, we can also place the United States among the losers in this new and uncertain reality. An overwhelming 85% of Americans say that political violence is on the rise in the country. The swift consolidation of Donald Trump’s presidential power in his first year since returning to the White House is leading the United States towards an authoritarianism that is rapidly eroding the rule of law. Democracy and the independence of the US institutions are the losers. The Trump administration has steadily pushed the boundaries of presidential power: it has declared national emergencies to justify extreme policy measures; it has fired dozens of inspectors general and prosecutors; and it has sidelined the directors of independent agencies. It was the president himself who declared on social media in February 2025: “He who saves his country does not violate any laws.”

In 2026, the United States will mark the 250th anniversary of its independence, coinciding, paradoxically, with the fear of election interference in next November’s midterms. These elections halfway through the presidential term will test the resistance of US democracy, but they could also be an opportunity for the electorate to curtail the administration’s agenda. So far, the inability of Congress to hold the president to account has put greater pressure on a divided judiciary: a Supreme Court that leans clearly to the right and increasingly diminished lower federal courts.

In this legal war, the US legal profession points to over 70 lawsuits filed against President Trump and his administration. According to the American Bar Association (ABA), they “knowingly undermine the division of powers between the executive and congressional branches set out within the US Constitution.” The Trump administration, meanwhile, has launched a frontal assault on civil rights, lashing out at law firms that have challenged it, installing the president’s personal lawyers into positions throughout the executive branch and defying court orders when federal judges consider its actions unlawful. This defiance of the law also includes the deportation of US citizens and others without due process, the arrest of student demonstrators without charge, the inappropriate use of physical force, retaliatory criminal prosecutions of elected leaders and non-profits, or censoring locals and foreigners alike, as well as direct attacks on the press in the exercise of its functions.

Since the start of Trump’s second administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) spending on detaining immigrants has rocketed. Some estimates say that by 2026 its budget could triple to $30bn, with extrabudgetary support guaranteed by the “Big Beautiful Bill”. In November 2025, the number of ICE detainees reached 66,000, a record high, and the government continues to reopen, extend and build new detention centres in support of the declared aim of “mass deportations”. The Supreme Court will also consider putting President Trump’s proposal to “limit birth right citizenship” back on its docket in 2026.

The White House invoked the Insurrection Act of 1807 – designed to combat an internal armed rebellion – to justify the deployment of the National Guard in Los Angeles, Washington and Memphis, as well as to demonstrations in Portland and Chicago. The move was interpreted as an attempt at internal militarisation of the United States. The courts intervened to halt it.

The erosion of US institutions is even threatening American leadership of the global financial system. The Trump administration continues to put pressure on the Federal Reserve (Fed). What began as blatant rhetorical demands to lower interest rates has morphed into a much deeper effort to redefine the Fed’s role and mandate; threats to dismiss the chair of the central bank, Jerome Powell (sparking a reaction in the markets); and the controversial appointment of the chief economic adviser to the White House, Stephan Miran, to temporarily cover a vacancy on the Fed Board. On top of that, the attempt to fire another of its governors, Lisa Cook, has reached the Supreme Court, which will hear the case in 2026. No president had dismissed a sitting Fed governor in its 112-year history.

Furthermore, a profound economic change is underway that blurs the line between the public and private sectors. Conflict of interest has been normalised (Trump’s private business deals, company payments to the government to modify legislation, firms paying for export licences or investing for fear of reprisals from the administration or the president’s circle, and so on). There is also a growing government footprint on company boards and policy. Washington is acquiring equity stakes in firms operating in key strategic sectors like semiconductors and critical minerals.

Given all this, it is reasonably safe to say that 2026 will be a year of decline in freedoms and the quality of democracy on a global scale. The West is seeing the steepest regional fall, with the United States, Greece and Italy at the forefront of these autocratisation processes, according to the V-Dem report. The world today has 88 democracies (liberal and electoral) and 91 autocracies (electoral and closed). Until 2024, the proportion was the other way around.

This sense of disorder that is dragging the world into a forced readjustment is not as chaotic and volatile as the uncertainty it causes. It is a comprehensive rethinking of the international order with its own agenda: backsliding on rights, fragmentation in trade relations and distrust of multilateral governance.

CIDOB calendar 2026: 80 dates to mark in the diary

January 1 – Changeover in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Bahrein, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Latvia and Liberia, elected in 2025, will join the council as non-permanent members, replacing Algeria, Guyana, Sierra Leone, Slovenia and South Korea. Meanwhile Denmark, Greece, Pakistan, Panama and Somalia, who were elected in 2024, will start their second year as members.

January 1 – Cyprus takes over the six-month rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union (EU). The Cypriot president, Nikos Christodoulides, will continue the 18-month programme shared with the Polish and Danish presidencies in 2025, in line with the EU Strategic Agenda 2024–2029. Among the most pressing challenges is Russian-driven hybrid warfare, which stepped up alarmingly in 2025 with the proliferation of disinformation, cyberattacks, violations of European airspace by fighter jets and “unidentified” drone incursions, and sabotage of submarine cables.

January 1 – Switzerland takes up the yearly rotating chairpersonship of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). The European country, one of the continent’s few remaining neutral states, will lead OSCE activities, forming a troika with Finland and Estonia. Geopolitical polarisation that pits Russia against the West continues to fester within the organisation, preventing consensus and blocking agendas, projects and election observation missions. Russia has vetoed the OSCE’s work in Ukraine.

January 1 – Bulgaria adopts the euro. After meeting the five convergence criteria on inflation, deficit, debt, interest rates and monetary stability, Bulgaria – which joined the EU in 2007 – will bid farewell to the lev and become the 21st member of the eurozone. High inflation had delayed accession to the monetary union as many as three times since January 2024.

January 15 – General elections in Uganda. Yoweri Museveni, who seized power in 1986 after waging a guerrilla war, has won six presidential elections in the last 30 years. While they have been pluralistic, none of them met democratic standards. In 2026, Uganda’s indefatigable strongman, a key figure in regional geopolitics, is seeking his seventh five-year term at the age of 81.

January 18 – Presidential elections in Portugal. Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa was elected president in 2021 for a second and final five-year term. The four candidates in the running to take over from him are: Admiral Henrique Goveia e Melo (an independent), Luís Marques Mendes (from the ruling Social Democratic Party), André Ventura (the leader of Chega) and Antonio José Seguro (from the Socialist Party).

January 19 to 23 – 56th Annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (Davos forum). The think tank and advocacy network that each year gathers a multidisciplinary ensemble of personalities in the Swiss town of Davos has chosen the theme “A Spirit of Dialogue” for its 2026 encounter. This year five global challenges will be under discussion: cooperation in a contested world, unlocking new sources of growth, investing in people, responsible innovation and prosperity within “planetary boundaries”.

February 1 – General elections in Costa Rica. The Costa Rican constitution prohibits the consecutive re-election of the head of state, which means Rodrigo Chaves, who was elected in 2022, must pass on the presidential sash on May 8, 2026. The date with the ballot box takes place on a fractured political landscape following Chaves’ split with his own party, the centrist Social Democratic Progress Party (PPSD), and the fragmentation of the “Rodriguista” ruling party group. The new Sovereign People’s Party (PPSO) and its candidate, the former minister Laura Fernández, are hoping to rally this sector’s support.

February 5 – Artemis II mission to the Moon. Following several postponements, NASA plans to begin its second mission of the Artemis space programme, the first to be crewed. The plan is for the Orion spacecraft, propelled by the SLS rocket, to leave the Earth’s orbit, perform a flyby of the Moon and return to Earth in ten days. If all goes well, the following mission, Artemis III, also crewed by four astronauts, will mark humans’ first return to the Moon’s surface since the lunar landing by Apollo 17 in 1972.

February 8 – Snap general elections in Thailand. Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, leader of the Bhumjaithai party, called for the dissolution of Parliament due to the inability to reach a consensus with the Prachachon party, his coalition partner, on constitutional reform. The early election call reflects the worsening of the Thai political crisis, which coincides with increased tensions on the border with Cambodia.

February 13 to 15 – 62nd Munich Security Conference (MSC). Held annually since 1963, the MSC is recognised as the premier independent forum for debate on international security and is attended by hundreds of policymakers and high-level officials. The 2026 edition will bring back echoes of 2025, when the US vice president, JD Vance, signalled the breakdown of the transatlantic consensus on the war in Ukraine and the conceptual abyss that separates the new Trump administration from the European allies.

February 21 and 22 – 39th Ordinary Session of the African Union (AU), Ethiopia. An annual gathering of AU heads of state and government to tackle the continent’s priorities: peace and security, economic integration, the financing of sustainable development, climate resilience and Agenda 2063. The leaders are expected to adopt the “Africa Water Vision and Policy” and debate the reform of the UN Security Council. Six member states – Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Madagascar, Niger and Sudan – are currently suspended following their respective military coups.

February – General elections in Bangladesh. The vote will determine the composition of the new parliament and government after the fall of the despotic regime of Hasina Wazed and her party, the Awami League, which is now banned. Hasina was ousted in August 2024 following a month of mass protests. Since then, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus has headed a transitional government with the mandate to call new elections. Nearly two years on, two conservative nationalist parties are the contenders for leadership: the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), with Tarique Rahman in charge, and Jatiyo, led by GM Quader.

March 2 to 5 – 20th edition of the Mobile World Congress (MWC). A fresh edition of the world’s most influential mobile communication technologies and connectivity event, where device manufacturers, service providers, wireless carriers, engineers and scientists showcase the latest developments in the sector. In 2026, the MWC will focus on six themes: smart infrastructure, connected artificial intelligence (AI), AI for enterprise, AI nexuses, inclusive technology and game-changers.

March 5 – Legislative elections in Nepal. In September 2025, a Gen Z-led popular revolt cornered the Nepalese political class – labelled incompetent and corrupt – toppled K.P. Sharma Oli’s government and installed the retired judge Sushila Karki as caretaker prime minister. Apart from a return to democratic normality, the elections in 2026 must produce a government that meets the demands of Nepalese society. The Rastriya Swatantra Party of Rabi Lamichhane could make hay of the rejection of the elites.

March 8 – Federal elections in Baden-Württemberg. In these elections, voters will decide the composition of their federal state's parliament and government. While polls predict victory for the Christian Democrats, the far-right party, Alternative for Germany (AfD), is expected to receive 21% of the vote – although they are aiming for 25%. During the year, elections will also be held in Rhineland-Palatinate (March 22), Saxony-Anhalt (September 6), and Berlin and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (September 20). According to a poll, almost half of Germans expect the AfD to have a federal leader in 2026.

March 15 and 22 – Local elections in France. Municipal councils and, in the big cities, metropolitan or arrondissement/sector (district) councils will be decided at the ballot box, as mayors and local representatives are chosen. In cities like Paris, Marseille or Lyon, changes will be made to separate the vote between central and district councils, breaking with the previous system. This is expected to bring about a greater division between metropolitan and local power. The results will be a pointer ahead of the next national elections.

March 22 – Presidential elections in the Republic of the Congo. The de facto dictator of Congo-Brazzaville, Denis Sassou Nguesso, is one of the longest-standing leaders in Africa and the world. His power stretches back to 1979 save for a five-year interval between 1992 and 1997, when the country was governed by the democratically elected Pascal Lissouba, but which ended in civil war. After confirmed fraud in the elections of 2002, 2009, 2016 and 2021, Nguesso, at 81 president for life, is sure to continue.

March – Legislative elections in Slovenia. In 2022, the party that won the most votes was the Freedom Movement (Svoboda), a new eco-liberal party led by the businessman Robert Golob, who formed a majority coalition government with the Social Democrats and The Left. Janez Jansa, three-time prime minister and veteran leader of the rightist Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS), returned to the opposition. In late 2025, the SDS was leading Svoboda in the polls, but both were flagging.

April 12 – General elections in Peru. Whoever wins the presidency, they will be faced with a basic challenge on July 28: complete the five-year term mandated by the constitution. Unstable Peru, which is also hit by a crime crisis, has had seven presidents since 2016, three of whom were removed by Congress while two resigned. The latest episode came in October 2025, when the dismissed Dina Boluarte was replaced by José Jerí. Congress is highly fragmented; the standouts among the numerous potential presidential contenders are Rafael López-Aliaga, Keiko Fujimori, Mario Vizcarra, Carlos Álvarez and César Acuña.

April 12 – Presidential elections in Benin. Benin’s is one of most stable and fluid political systems in Africa, although its democratic quality has declined. There have been four presidents of different political stripes since 1991. The current incumbent, Patrice Talon, was re-elected in 2021 and despite signs of authoritarianism he has not amended the constitution to stand for a third term. Furthermore, on December 7th, 2025, Talon fended off an attempted military coup. On January 11, there will be elections to the National Assembly, where the two parties underpinning Talon’s government (he has no party of his own), the Progressive Union for Renewal (UP) and the Republican Bloc (BR), form a broad majority. Romuald Wadagni, the finance minister, is running for the ruling parties.

April 18 – 75th anniversary of the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The Treaty of Paris of 1951, preceded by the Schuman Declaration of 1950 and signed by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany to jointly administer coal and steel, marked the start of the process of post-war economic integration and established the first of the three European Communities, the forerunners of the European Union.

April 26 – 40th anniversary of the Chernobyl accident. Four decades after the disastrous radioactive explosion at the nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine, the city of Pripyat and the rest of the exclusion zone remain abandoned. Today, the danger looming over Chernobyl comes from the invading Russian army, whose bombing raids jeopardise the electricity supply that is vital for the correct functioning of the protective shield covering reactor 4.

April – Official visit to China by Donald Trump. The US president announced this official visit, which would be the first in nine years, after being pleased with the outcome of his October 2025 bilateral (“G2”) meeting with Xi Jinping in Busan, on the sidelines of the APEC summit in South Korea. During the meeting, Trump agreed to cut tariffs on China from 57% to 47% in exchange for Beijing’s temporary lifting of its restrictions on rare earth exports and the resumption of US soybean purchases.

April – Legislative elections in Hungary. Viktor Orbán, prime minister of Hungary and the EU’s longest-serving leader, faces his first serious challenge at the ballot box after four straight absolute majorities for his Eurosceptic radical right party, Fidesz. Leading the polls since autumn 2024 is Respect and Freedom (TISZA), a pro-European conservative party founded in 2020 which has risen to prominence under the leadership of the MEP Péter Magyar, a former Fidesz member who now calls Orbán a “dictator” and “mafioso”.

April 27 to May 22 – Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference. This will be the 11th five-year review of the NPT of 1968, the key instrument for the control of atomic weapons, the civilian use of nuclear energy and disarmament, an enterprise currently at a low ebb. Four of the nine countries in possession of nuclear weapons – India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea – remain outside the NPT. In 2025, Iran’s nuclear programme triggered the alert at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). And the United States, Russia and China are expanding their arsenals; the first two are also considering resuming nuclear testing.

May 7 – Municipal elections in the United Kingdom. Over 4,000 council seats in England will be up for election, including those of the 32 London boroughs. There could be a repeat of the results of the local elections of May 2025, which delivered a resounding victory to Reform UK, the national populist right-wing party of Nigel Farage, and punished Kemi Badenoch’s Conservatives and the Labour Party of Prime Minister Kier Starmer with a humiliating third and fourth place, respectively (also behind the Liberal Democrats). Both are suffering in the polls.

May 15 – End of Jerome Powell’s tenure as chair of the US Federal Reserve. Powell was nominated by Donald Trump in 2017. But his restrictive monetary policy of raising interest rates drew criticism from the president, who labelled him an “enemy”. Following reappointment under Joe Biden, in 2025 Powell began to receive fresh rebukes and insults from Trump, who was eager to see a more aggressive drop in interest rates. The president’s possible appointment of a MAGA loyalist could undermine the credibility of the Fed, an independent central bank, and have a major impact on the markets.

May 24 – General elections in Cyprus. Nikos Christodoulides was elected president in 2023. He is an independent centrist backed by the Democratic Party (DIKO), the Socialist Party (EDEK) and Democratic Alignment (DIPA), which in the 2021 elections only obtained 17 representatives out of 56. Christodoulides has been governing with occasional legislative support from the centre-right Democratic Rally (DISY), the largest party in the House of Representatives.

May 31 – Presidential elections in Colombia. Preceded by legislative elections on March 8, which the ruling coalition is heading into without a majority, the presidential ballot in May will bring the four-year term of the controversial Gustavo Petro to a close. The assassination of right-wing presidential hopeful Miguel Uribe, rising violence from illegal armed groups and a row with the United States made for a tense 2025. The senator Iván Cepeda is the candidate for Petro’s party, Historic Pact, in a contest that promises to be open and hard-fought.

May – General elections in Lebanon. The peculiarities of the Lebanese system, with sectarian and clientelist dynamics that in the interest of confessional balance determine the composition of the republic’s institutions, reduce the prospects of change after legislative elections to a minimum. Save for the Free Patriotic Movement, all the main parties (the Maronites of the Lebanese Forces and Kataeb, the Shi’ites of Hezbollah and Amal, Druze and Sunnis) form part of the government or support it in parliament.

June 1 – General elections in Ethiopia. The second elections for Abiy Ahmed, the controversial prime minister of Ethiopia since 2018. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for his democratic reforms and peacemaking efforts, he has subsequently been challenged over his leadership during the bloody civil war against the autonomy movement in Tigray (2020–2022), his authoritarian drift and his inflammatory rhetoric, which hits neighbouring countries. Ethiopia is a parliamentary republic where Abiy’s multi-ethnic Prosperity Party is dominant; it has an indirectly elected ceremonial president.