The crisis of aid: ideal models for the future of development cooperation

Documents CIDOB: 18

The current aid crisis is not merely budgetary, but also structural, undermining the very justification for existing and relevance of the system itself. At the core of this crisis lies the inability of aid to respond to the tectonic shifts that have occurred in the international hierarchy, in the configuration of markets, and in both the experience and theory of development. This work examines such misalignment through five vectors: changes in the structure of international power; the revision of the diagnosis concerning the developing world; the plurality of objectives and agendas incorporated into cooperation; the need to redefine the scope of international financing; and the governance structures of the system. From this analysis, three “ideal types” emerge as potential pathways for reforming the cooperation system: focused; oriented towards international public goods; and diversified and shared. The author discusses the implications of each of these ideal types, advocating for the decolonisation of cooperation and the strengthening of multilateralism.

1. Introduction

The year 2025 opened with a series of landmark decisions by the Trump administration: withdrawing the United States from the Paris Agreement and from several United Nations agencies (including the WHO, UNRWA and UNESCO); reducing contributions to others (such as UNDP, OCHA and UNICEF); and dismantling the US Agency for International Development (USAID), thereby eliminating much of its programming. These measures are poised to exert a profound impact, not only because the United States accounts for roughly 30% of total international aid funding, but also due to the disengagement and discouragement they may trigger among other donor countries.

At the same time, a group of European donors – including France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland – announced cuts to their respective international aid budgets. In most cases, the justification offered is not ideological (the Netherlands perhaps being an exception) but rather the imperative to rebalance public finances or to recalibrate spending priorities, giving greater prominence to national strategic interests. Collectively, these measures will produce a substantial contraction in official development assistance (ODA) in 2026 and beyond, estimated at between one-fifth and one-third of current resources (DAC, 2025). The crisis afflicting aid thus has a first, inescapable budgetary dimension.

However, the convergence of decisions by governments of markedly different political persuasions suggests that, beyond the stated motives of each, there is a common climate of distrust and scepticism towards international aid. This sentiment is found both among those who reject the ethical foundations of international cooperation and among those who, while upholding such values, view the current configuration of the cooperation system as manifestly inadequate. Significantly, this critical stance is also embraced by many of the purported beneficiaries of such policies, who regard them as incapable of fostering a more equitable distribution of international development opportunities (Lopes, 2024).

The present aid crisis, therefore, extends beyond budgetary constraints to challenge the very relevance and legitimacy of the system. At the heart of this critique lies the erosion of the foundational pillars upon which the aid architecture was built: the uncontested dominance of a small group of wealthy Western countries; the stark North–South divide; the assumed “catching-up” effect attributed to transfers of capital and knowledge; and the (neocolonial) presumption that developed nations should serve as models for developing ones. Each of these premises is now under sustained challenge, placing the aid system in what may be termed a constitutive crisis (Klingebiel & Sumner, 2025). The world has irrevocably changed, and the cooperation system must either reinvent itself to meet the demands of a transformed landscape or resign itself to progressive irrelevance (Alonso, 2025).

Determining where the deficiencies lie and how to orient necessary reforms has thus become an essential task. Several recent contributions have engaged with this question (e.g., Gulrajani, 2022; Klingebiel & Sumner, 2025; Ahmed et al., 2025; Kumar et al., 2025; Glennie, 2025). This paper seeks to add to that conversation from a distinct vantage point. It proceeds from the assumption that the current crisis is driven less by the limited effectiveness of aid or by the fragmentation of the system – though these are factors – than by doubts surrounding its very rationale and institutional design. While any public policy requires a justificatory narrative, it seems unlikely that the present impasse can be overcome by a change in discourse alone (Aly et al., 2024). Furthermore, this search for new narratives can be counterproductive if, in order to garner support from policymakers, emphasis is placed on transactional purposes that are unrelated to development purposes or for which other public policies are more appropriate. It is doubtful, moreover, that there can be a single narrative for development cooperation when it encompasses diverse agendas (humanitarian, poverty reduction, public goods, mutual interest), each with its own normative principles and distinct purposes.

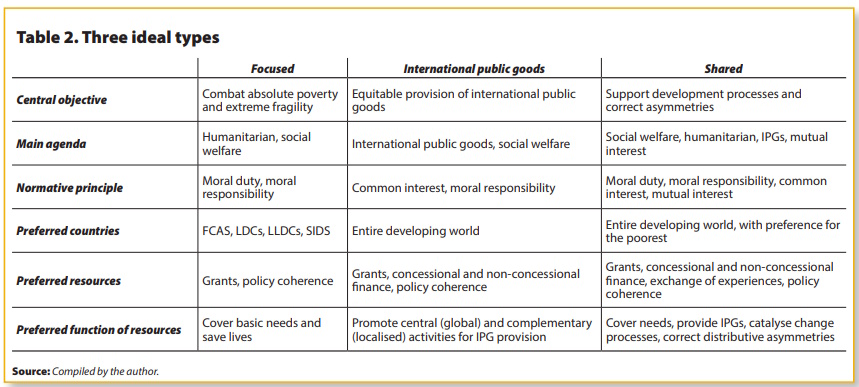

In addressing this complexity, the aim here is not to construct future scenarios – which are inherently unreliable given the fluidity of the environment – but rather to delineate certain ideal types (in the Weberian sense) towards which the cooperation system might evolve. An ideal type does not seek to reproduce empirical reality but to distil the essential components of a model that can serve as an analytical benchmark. The exploratory exercise presented in the following pages yields three such models: a focused model; a model oriented towards international public goods; and a diversified–shared model.

Two preliminary clarifications are in order. The first concerns the scope of the analysis: making effective progress on the sustainable development agenda requires a profound reform of the international development financing framework, but our focus here will be on the crisis affecting only one of its elements: development cooperation. Furthermore, although the crisis affects the entire cooperation system, much of the analysis will focus on ODA, which is its best-defined and most questioned component.1 Second, the study does not attempt to examine every factor contributing to the present crisis but concentrates instead on those most relevant to identifying alternative models that could inform reform.

The paper begins by characterising the crisis, followed by five sections examining key drivers of change: shifts in international hierarchies, evolving diagnoses of the developing world, the plurality of agendas, the scope and metrics of international financing, and the governance structures of the system. A concluding section synthesises the discussion and its implications.

2. An existential crisis

International aid has always been a policy with a fragile political foundation. Although Gunnar Myrdal (1970) described it as one of the most interesting innovations in the post-war international order, aid has been continually compelled to justify its existence to those who have regarded it as unnecessary, ineffective or even harmful. This is hardly surprising, given the contradictory nature of its underlying purposes, where altruism coexists with self-interest, empathy with technocratic arrogance, and cooperative action with strategic calculation. Its configuration as a hierarchical system – with a pronounced neocolonial imprint, dominated by donors and largely based on discretionary relationships – links aid to relations of subordination and dependency, as well as to a paternalistic discourse clearly at odds with the stated objectives of autonomy and empowerment for recipient countries (Ziai, 2016). The fact that aid beneficiaries are not citizens (and therefore not voters) of the donor country places this policy at a clear disadvantage in the competition for public resources in donor countries (Martens et al., 2008). It is, moreover, a low-profile policy on donors’ public agendas, wrapped in a technocratic language that attracts the attention of a small community of policymakers. It is therefore unsurprising that aid is among the first policies to suffer budget cuts in difficult times, and one of the most questioned when international conditions turn adverse.

Such was the case in the 1990s, when ODA fell by nearly 24% in real terms and did not return to its 1992 levels until a decade later, in 2002. While this decline coincided with the financial crisis affecting European countries in the early 1990s, the decisive factor was the collapse of the socialist bloc, which eliminated aid’s function as a tool for cementing alliances and securing loyalties during the cold war.

The Millennium Agenda, launched in 2000, reinvigorated international aid, positioning it as a key component of the new global agenda. Yet by 2005 the system had entered another period of stagnation, from which it did not emerge until nine years later. This setback coincided with the economic difficulties generated by the 2008 financial crisis.

From 2014 onwards, aid embarked on a renewed upward trajectory, which – with some interruptions – continued until 2023. This period of growth was driven by: (i) an expansion of DAC membership, with nine countries joining after 2013; (ii) the political momentum generated by the adoption of the ambitious 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (although this granted aid a less central role than the Millennium Agenda); and (iii) the increasing salience of new geostrategic objectives, including the containment of migration flows, competition with China and Russia over spheres of influence, and the response to refugee crises and humanitarian emergencies (such as those in Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Ukraine and Palestine).

In 2024, the growth trajectory of aid entered a period of decline that is likely to continue in the coming years. Among the causes are, once again, fiscal constraints: in 2024, nine DAC members – including the United States, France and the United Kingdom – reported public deficits exceeding 4% of GDP. Moreover, aid now competes with other prominent national strategic priorities. This is the case with defence and security expenditures, which have an added importance among European donors following their agreement within NATO to substantially increase spending in this area. Both fiscal adjustment and expenditure reallocation underlie the announced cuts.

Another defining feature of the current crisis is the rising influence of nationalist and ultraconservative parties (and governments) aligned with the far right, hostile to multilateral action, and pursuing agendas at odds with the goals of environmental sustainability, social equity, respect for diversity, and human rights of migrants. These actors conceive international engagement as a zero-sum game, grounded in confrontation, show little regard for inherited international rules and agreements, and adopt an essentialist, exclusionary vision of their respective political communities. Such an ideological framework is largely incompatible with the values underpinning the development cooperation system (Hackenersch et al., 2022).

Given the weight of these two factors, there may be a temptation to attribute the crisis in the aid system solely to them. This would be a mistake: the crisis predates Trump and the looming budgetary retrenchment. It is a constitutive crisis, one that has developed over time as a result of the aid system’s inability to respond with the necessary depth and urgency to the changes that have occurred in international hierarchies, market configuration, and development theory and practice. This mismatch between the existing model and the demands of reality explains the profound and structural nature of the crisis, whose roots extend back in time. This is evidenced by the substantial body of work on the subject produced over the past two decades (e.g., Severino & Ray, 2009; Kharas, Makino & Jung, 2011; Alonso, 2012; Kharas & Rogerson, 2012, 2017; Sumner & Mullett, 2013; Hulme, 2016; Klingebiel, Mahn & Negre, 2016; Glennie, 2021; Ahmed et al., 2025). Despite differences in approach and degree of radicalism, these studies share a common call for a fundamental transformation of the aid system.

The DAC has sought to respond to this demand through two reform processes during the period. The first was associated with the Aid Effectiveness Agenda, launched in Paris in 2005, reaching its fullest expression with the agreement adopted in Busan in 2011 and the subsequent creation of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation (GPEDC). Despite its initial momentum, this agenda gradually lost traction, and its reformist impact has left little trace on donor behaviour (Bracho, 2017). Recently, on the occasion of the Fourth Conference on Financing for Development, an attempt was made to revive this agenda through the 2030 Pact for Effective Development Cooperation, within the framework of the Seville Platform for Action, although it is too early to predict the outcome of this proposal.

The second reform initiative began in 2012, aiming to “modernise” ODA measurement and define a broader metric for development financing: the Total Official Support for Sustainable Development (TOSSD), accompanied by the creation of the International Forum on TOSSD (IFT) as the body responsible for monitoring. The outcome of this process of reforms remains ambiguous: while some decisions have been pertinent, concerns about the potential overestimation of ODA persist, and the new metric has yet to gain widespread acceptance.

In sum, the period has seen institutional changes in the aid system, but these have been too modest to address the tectonic shifts in the international landscape. Indeed, what has most characterised the system has been its powerful institutional inertia – its inability to evolve in step with social realities.2 To deepen the analysis and bring potential alternatives into view, it is essential to first examine some of the fundamental dilemmas confronting the aid system.

3. Shifts in global hegemony

At its core, the current aid crisis reflects the erosion of the international hegemony of traditional donors. Two major transitions have been particularly relevant in this regard. The first stems from the shift in primacy from states to markets, which has reduced the relative weight of official financing (including ODA) in favour of resources mobilised through capital markets. The second involves the relocation of global economic growth poles towards the Pacific, accompanied by the decline of the previously dominant bloc (United States–Canada–European Union–Japan) and the rising influence of new powers from the developing world.

The first of these processes is well documented. In the early 1970s, aid flows to developing countries exceeded by more than 1.5 times the combined inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and migrant remittances, the two most stable forms of international private flows. Five decades later, the situation is entirely different: on aggregate, investment and remittances are now eight times greater than aid. Only in the lowest-income countries does aid continue to hold a prominent place in resource provision, as in the case of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), where it accounts for over 70% of international financing. The same shift is evident, significantly, in public-sector financing. In 2010, official resources (grants and loans) represented 63% of the funds received by public institutions in developing countries; a decade later, this share had dropped to 52%, while the proportion sourced from financial markets (export credits, financial institutions and sovereign bonds) increased correspondingly (World Bank, 2021). In short, capital markets have become more accessible to developing countries –though not to all – and, as a result, private actors have assumed a greater role in development finance. This dynamic calls into question the rationale for aid, originally conceived as a response to the inability of poor countries to access financial markets.

This process has been accompanied by a loss of weight and leadership among Western powers.3 In 1990, the bloc on which the aid system was built accounted for nearly half of global GDP (in PPP terms); by 2023, its share had fallen to just one-third, while that of so-called emerging market economies had risen from 28% to 45%. The original BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) increased their share of global GDP from 17% to 33% over this period.

These changes have been reflected in global governance. Half the members of the G20 are emerging markets and, as the recent summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation reveals, some of them are willing to forge their own alliances and global strategies. Some of these countries have established their own multilateral institutions, in part in response to their underrepresentation in the Bretton Woods institutions. China spearheaded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, while the BRICS created the New Development Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) – institutions with functions similar, albeit on a smaller scale, to those of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, respectively. In addition, there are other pre-existing multilateral institutions also promoted by emerging economies, such as the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and the Islamic Development Bank, among others.

The Global South’s growing presence in the international order is also visible in the expansion of South–South cooperation (Mawdsley, 2012, 2019). The absence of agreed reporting systems makes it difficult to determine the precise magnitude of this type of cooperation, but rough estimates suggest it accounts for at least 15–20% of total ODA. In any case, the figure is of limited relevance because many of these cooperation providers reject the ODA classification altogether. In many cases, South–South cooperation is based on the exchange of experiences rather than the mobilisation of financial resources; yet where financial flows are significant, their scale is noteworthy. For instance, between 2010 and 2019, China extended loans to developing countries worth USD 243bn –equivalent to the combined lending of Japan, France and Germany – and among the ten largest lenders to the developing world, six were emerging providers (China, Russia, India, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates) (World Bank, 2021).

These countries emphasise features in their cooperation that differ from traditional aid, such as horizontal relationships, similarity in developmental challenges, reciprocity, and respect for national sovereignty. In practice, South–South cooperation does not always conform to these ideals; indeed, it displays considerable heterogeneity, with some providers replicating patterns of traditional donors (Santander & Alonso, 2017). Emerging donors are sometimes criticised for failing to meet DAC-agreed standards (such as untied aid), but it is worth noting that they were not involved in defining those standards – and that traditional donors do not always meet them either.

In sum, the convergence towards a homogeneous cooperation model once encouraged by the DAC has given way to a process of diversification and competition among different models, many led by developing countries themselves. As a result, aid recipients now face a more varied landscape of potential partners and funding sources, albeit at the cost of navigating a more fragmented cooperation system.

The scenario described above raises two important questions. First: is aid still necessary in a world where developing countries (at least some of them) can access capital markets? Some will answer in the negative – and this view underlies part of the current aid crisis. However, two (nonexclusive) arguments point in the opposite direction. The first is that many countries still lack access to market financing – or cannot secure it on appropriate terms – such as those in conditions of extreme fragility or facing structural constraints (e.g., LDCs, landlocked developing countries [LLDCs] and small island developing states [SIDS]). One possible alternative, then, would be to maintain aid but focus it more explicitly on the countries with the greatest needs – referred to here as the “focused model”.

A second, more ambitious response draws inspiration from mechanisms used in many developed countries to address internal territorial inequalities, such as the European Union’s structural funds. These exist not because regions lack access to capital markets, but because certain strategic investments can only be promoted with public resources; because such resources can act as catalysts for other transformative changes; and because they help preserve social and territorial cohesion. By analogy, the development cooperation system could serve – albeit modestly – as a mechanism to perform this function at the global level, albeit in a highly decentralised fashion. This would require a diversified agenda of goals and instruments to meet the needs of countries in very different circumstances; clear criteria for fund eligibility; a contributions system closer to mutuality; and inclusive governance. We refer to this option as the “diversified–shared model.”

The second question arises from the shifts in international hierarchies: should we build on the existing system and pursue incremental improvements, or is a wholesale redesign in order? (Ahmed et al., 2025). Some will see the first option as a cautious approach that preserves a valuable legacy of norms and standards, improves it through gradual reforms and expands its reach through new accessions, while avoiding a wholesale challenge to the system. This has been the DAC’s path, through its reform of ODA measurement and the creation of TOSSD. However, this approach faces the reality that many new cooperation providers feel alienated from – or outright opposed to – that legacy and neither are nor wish to become DAC members. The likely outcome of this path is to consolidate fragmentation of the cooperation system.

Alternatively, one could envision a more inclusive response: redefining the cooperation system as an open arena for the visions and capacities of all countries willing to engage in development action, thereby generating new agreements on metrics, standards and eligibility criteria out of this constitutive diversity; agreements that are compatible with an appropriate distribution of responsibilities, which may be differentiated according to the capacities of each group of countries, being less stringent for developing countries (Bracho, 2024). Some elements of the DAC’s legacy could be retained, but the process would have to remain open to deliberation and consensus-building, necessarily accompanied by a redefinition of development cooperation governance.

4. From the great divide to gradients of development

The shift in international hierarchies has been mirrored by a parallel process of differentiation within the developing world. When aid was first conceived in the 1950s, the international landscape appeared sharply divided between a prosperous North and an impoverished South. This diagnosis was not entirely accurate, as many countries (particularly in Latin America and the Maghreb) occupied intermediate strata, but it was a broadly accepted approximation. Around 60% of the world’s population – living in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and East Asia – had a per capita income barely equivalent to 7% of that in the United States.4 Worse still, their historical trajectory suggested a deepening of disparities: between 1870 and 1950, the United States had tripled its per capita income, and Western Europe had doubled it, while the three poor regions mentioned above had increased theirs by only 16%. Aid emerged as an instrument to narrow this profound gap.

Since then, countries have followed divergent paths. Relative to US per capita GDP, sub-Saharan Africa became poorer between 1950 and 2022, its share declining from 8.7% to 5.7%. By contrast, East Asia and South Asia moved in the opposite direction, rising from 7% in both cases to 37% and 14%, respectively. Latin America maintained its status as a middle-income region, stabilising around one-quarter of US per capita GDP, while the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region advanced from 15% to 34%, albeit with considerable variation among its members.

As a result, countries that were until recently recipients of international aid now present themselves as dynamic economies. Some have joined the OECD (e.g., Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica), while others await accession; some, despite modest starting points, have launched impressive growth processes, becoming attractive markets for international investors (e.g., Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines); and a group have attained the status of new powers (e.g., China, India, Mexico, Brazil). Significant disparities between the richest and poorest countries remain, but rather than a yawning chasm between them, we now find a populated continuum – a world of development gradients, with numerous countries occupying intermediate positions. In this context, is there still a place for aid?

Three potential answers can be envisaged. The first comes from donors seeking to redefine aid’s original binary structure while narrowing the circle of recipient countries. This would mean going back to basics, meeting essential needs and directing resources towards countries most in need: those in humanitarian crisis, those facing serious structural obstacles to development (such as LDCs) or those in conditions of extreme fragility. These are the most disadvantaged countries, home to the bulk of global poverty. The 61 countries that the OECD classifies as experiencing extreme or high fragility account for just one-quarter of the world’s population, but they contain 72% of people living in extreme poverty. This approach would transform aid into a specialised policy focused on combating extreme poverty, providing humanitarian assistance and – where relevant – supporting state building programmes (the focused model).

A second response comes from those who believe that, with the North–South divide blurred, cooperation should be guided less by what separates countries than by what unites them – by what they mutually require – namely, the provision of international public goods (IPGs).5 This shift has been reinforced by the global experience of COVID-19 (Calleja et al., 2022). Since many IPGs – such as peace, financial stability, global health, and the protection of climate and biodiversity – are crucial for progress, it is reasonable to allocate part of development financing to their provision. Although estimates are imprecise, DAC data indicate that around 57% of ODA, on average, between 2016 and 2020 was devoted to IPG, up from just 30% a decade earlier (Elgar et al., 2023). However, the overlap between the two agendas is not complete: not all IPGs have development impacts, nor are all development goals IPGs. This means that what might be called the IPG model could exclude important development objectives, among others those related to distributional issues. It also shifts the underlying rationale of the policy: whereas development cooperation pursues redistributive aims and seeks to benefit poor countries preferentially, the IPG agenda focuses on correcting externalities, benefiting both poor and rich countries alike (although not necessarily to the same extent).

A third option sees cooperation as a tool to support a complex development agenda, with the mission of accompanying countries in their (primarily endogenous) development processes, mitigating obstacles, and addressing the asymmetries of international markets. Such a policy must operate across the multiple dimensions of development, tailoring its priorities and instruments to the different stages through which countries pass. It should be open to contributions from all countries able to provide them – not only the wealthy –and adopt a transformative, long-term perspective rather than a purely assistance-oriented one. It should also establish shared allocation criteria and give a central role to multilateral bodies. This is the diversified–shared model.

While each of these options has its merits, only the third fully mobilises the capacities of all countries, regardless of income level, in pursuit of the international development agenda, from a standpoint of mutual responsibility and respect. It is grounded in the conviction that no country is so poor that it has no valuable experiences to share, nor so rich that it can afford to ignore the rest. Applying the principle of mutuality – also advocated by the Global Public Investment initiative (Glennie, 2025) – some countries would be net donors and others net recipients, much as occurs with the European Union’s structural funds and certain international mechanisms (such as the Global Fund and the Adaptation Fund).

5. Multiple goals, varied narratives

The original purpose of aid was unequivocal: to enable countries of an impoverished South to converge towards the conditions of a prosperous North, drawing on two factors – capital and technical knowledge – which, being abundant in the wealthy world, were assumed to be key to fostering growth in poorer countries. This approach was supported by the leading contributions to the then emerging development theory (Nurkse, 1953; Rosenstein-Rodan, 1943; Myrdal, 1957, among others). Inspired by modernisation theory, this vision further assumed that economic growth was the engine driving the other changes – social, political, cultural – implicit in the development process, and that rich countries provided the model to which poorer countries should aspire.

Today, none of these assumptions holds true. We now know that development is a complex process, unfolding across multiple dimensions that do not necessarily progress harmoniously; that the experience of developed countries, far from being exemplary, is a source of problems (such as environmental degradation) to be avoided; and that there is no single path to development, but many, shaped by diverse factors. The certainty of the past has given way to more complex, uncertain and national-specific prescriptions (Rodrik, 2009; Alonso, 2024), leaving international aid in a state of painful theoretical orphanhood.

The reaction to this vacuum took two forms. On the one hand, donors tended to refocus their aid on social dimensions – health, education, poverty – where their contribution appeared more clear-cut. This shift was influenced both by the pressure of NGOs, which operate predominantly in these fields, and by donors’ desire to enhance their international reputation by emphasising the social content of their aid. While this change may be justified by the accumulated social deficits in developing countries, it has also resulted in a decline in the transformative, long-term components of aid, in favour of more short-term and assistance-oriented interventions.

The uncertainty over the determinants of development had a second consequence: the progressive expansion of the agenda, incorporating more objectives into development action. This expansion was further facilitated by the proliferation of actors within the cooperation system, each with their own visions and priorities. Thus, alongside the foundational aims of reducing poverty and inequality, today’s development agenda includes as obligatory goals the promotion of health and education, institutional strengthening and good governance, gender equality and democratic consolidation, social dialogue and cultural diversity, peacebuilding, and environmental sustainability, among others.

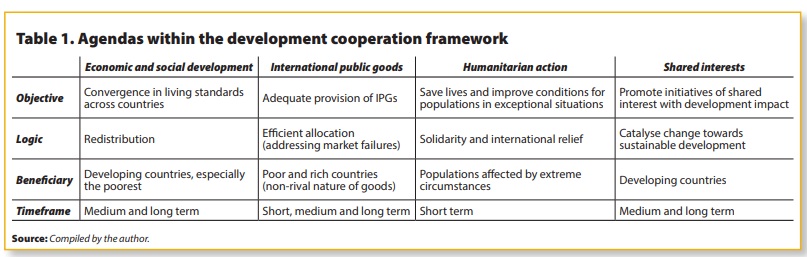

While no one disputes the importance of these aims, it must be acknowledged that many belong to distinct domains of work, differing in their underlying logics, timeframes and desirable resource allocation criteria. The undifferentiated integration of all these agendas under a single framework can only generate confusion. For this reason, it is useful to distinguish at least four broad agendas (Table 1).

The first is the traditional aid agenda, aimed at fighting poverty and promoting the economic and social well-being of low- and middle-income countries. This agenda is grounded in the logic of redistribution, conceiving aid as a decentralised (and therefore suboptimal) system for redistributing development opportunities on a global scale. In line with this nature, resource allocation should follow progressive patterns – giving more to those with less – and is conceived as a medium- to long-term endeavour, since this is the timeframe in which development results can reasonably be expected.

A second agenda concerns the provision of international public goods (IPGs), which operates not in the domain of redistribution but of the allocation of goods characterised by significant market failures (notably, high externalities). Efficient allocation in this case may not necessarily follow a criterion of national need or deprivation – either because the investment must be undertaken at the international level (e.g., developing a malaria vaccine) or because its effectiveness requires concentrating efforts in countries other than the poorest (e.g., climate mitigation, which must target major emitters). By virtue of the non-rival nature of these goods, their benefits extend to both rich and poor countries, though not necessarily to the same degree.

A third agenda relates to humanitarian action, which has gained increasing prominence in recent times due to the succession of conflicts, disasters and extreme climate events. This agenda encompasses measures linked to risk management, peacebuilding, disaster and conflict response, and the reception of refugees. Although the “triple nexus” approach, agreed at the Istanbul Humanitarian Summit, calls for linking development, peace and security, and humanitarian agendas, the latter retains a distinctive domain. Its ultimate rationale lies in the principle of prevention, protection and recue, with the aim of saving lives and improving the conditions of populations facing extreme survival risks. It is thus essentially short-term in nature and highly concessional in financing (preferably grants).

A fourth agenda is more controversial: it operates at the intersection of the economic (and potentially political) interests of donor and recipient, in actions with an impact on sustainable development. This domain encompasses South–South cooperation, as well as the scope of TOSSD, integrating interventions that generate direct positive impacts on sustainable development conditions, even when this is not their primary or sole objective. Advocates of promoting transactional narratives in the field of aid assume the prevalence of this logic, based on mutual interest.

Although relevant, this is a delicate agenda, in which reciprocity can easily be distorted by the asymmetries of power and resources that exist between countries (more acute in North-South cooperation than in South-South cooperation), which can lead to the donor’s own interests, sometimes with little connection to development purposes (e.g., border control in the face of migration), being passed off as mutual interests.

Within this framework, two contentious lines of action have gained prominence in recent years. The first is the securitisation of aid: using aid resources to advance the donor’s national security objectives, real or perceived. While this tendency is observable in several areas, the most notable example is migration policy (Pinyol-Jiménez, 2025). Framed as a threat to host-country security, aid resources are deployed to reduce migratory pressure by reinforcing border controls at the source, implementing return agreements or paying third countries to host irregular migrants. The European Union has made intensive use of this approach in its efforts to manage migration (Kumar et al., 2025).

The second line of action reflects the rising prominence of private actors in development cooperation. While the goal of aligning private investment with sustainable development objectives is laudable, the far more questionable assumption that mobilising private capital should be a universal aim of aid, and the yardstick for judging “smart aid”, is problematic. It may be justified to resort to blending financing and de-risking instruments (guarantees, for example) as a means of mobilising additional resources, but the objective should be development impact, not resource mobilisation per se.

There are, then, differences between these agendas, but also overlaps and linkages that can enable them to reinforce and complement each other. In this context, some argue that the most appropriate option for the future is to adopt an integrated approach (akin to the 2030 Agenda) as a way to capitalise on the interdependencies between the different domains. Others contend that such integration has led some agendas to “vampirise” others, and thus call for greater autonomy for each, particularly the humanitarian and sustainability agendas. A third possibility would be to maintain cooperation as an overarching framework encompassing all four agendas, while establishing differentiated commitments, resources and reporting systems to allow for specific narratives and monitoring for each (Melonio et al., 2022).

6. Beyond ODA

ODA is a recognisable metric, but it is too narrow to capture the growing diversity of forms and instruments of development financing. Its content was defined in the early 1970s on the basis of three core criteria: (i) the objective of contributing to development; (ii) the official origin of the resources and a minimum concessionality threshold (set at 25% relative to market terms); and (iii) the existence of eligibility (and graduation) rules linked to countries’ per capita income. These criteria have remained largely unchanged, with only minor adjustments, some of them controversial, such as allowing donors to count as ODA resources that never leave their borders, a practice that has gained prominence due to the rising costs of hosting refugees. For critics, counting domestically disbursed costs is a way of inflating ODA figures and undermining its credibility.

In recent years, ODA reporting has also been challenged by three factors: falling interest rates, which undermined the agreed concessionality calculation; the proliferation of financial instruments available to donors (such as equity, quasi-equity or guarantees), which were poorly addressed in reporting systems; and the ambition of the 2030 Agenda, which suggested widening the focus beyond ODA. To address these challenges, the DAC decided in 2012 to initiate a reform of its reporting procedures. Within this process, criteria for counting peace operations, refugee hosting and debt relief were reviewed, but the two most substantive changes concerned the measurement of concessionality and the reporting of private sector instruments (PSI).

The concessionality calculation, defined in the early 1970s, relied on a fixed reference discount rate (10%), at the same time as the DAC consolidated a net-flows valuation system under which the face value of loans was adjusted by deducting repayments from previous operations. Over time, financial market conditions diverged significantly from the agreed discount rate, enabling some donors to report as ODA loans that were in fact extended on near-market terms. To avoid this, more realistic discount rates were defined and differentiated by country groups, and a transition was made to a valuation system based on the grant equivalent of each operation.6 This harmonised the treatment of grants and loans and eliminated the distortive effect on annual commitments caused by loan repayments, albeit at the cost of losing the reference to total transferred flows. However, doubts remain about the chosen method of measuring concessionality (which differs from that of the World Bank), the suspicion that the new discount rates overvalue aid and, above all, the conviction that an opportunity was missed to explore a measurement system that does not focus solely on the “donor’s effort” (approximated through concessionality) and gives more importance to the development impact of the flows.

Similar ambiguity arose over the treatment of PSI operations. The final decision was to adopt two possible approaches: one focused on the institutions undertaking these activities (particularly development finance institutions) and another based on the instruments used (loans, equity, guarantees and hybrid instruments). The reporting framework requires the use of two concepts that are inherently difficult to measure: the additionality of the funds and the concessionality of the resources, the latter being especially elusive in operations with variable returns. It is too early to assess the consequences of the chosen approach, but some voices warn that it risks subordinating ODA to activities aligned with private profitability criteria (Craviotto, 2023).

Beyond these reforms, the core problem is that the concept of ODA itself is very limited and excludes important mechanisms of development finance. Much of the investment required for the climate, digital and productive transitions in the developing world will have to be supported by official financing instruments with widely varying degrees of concessionality, many of which outside the ODA perimeter. For a broad range of middle-income countries, such flows may be more relevant than aid, and could become even more so if multilateral development banks advance their modernisation and reform agendas, as suggested by the G20.7

These considerations led the DAC to create a new, broader metric to complement ODA: TOSSD. This measure captures all officially supported resources that have a direct impact on sustainable development, regardless of concessionality level. Built on two main pillars – cross-border resources and expenditures targeting global challenges and public goods – it also includes, as a third component, estimates of private resources mobilised with public support. Figures reported in 2023 (USD 544bn) illustrate the broader scope of TOSSD, which is 2.4 times the volume of ODA (USD 223bn), or 2.1 times excluding mobilised private resources.

TOSSD was created with a dual purpose: to provide a more comprehensive and transparent picture of officially supported financial resources for sustainable development, and to establish a universal metric capable of accommodating contributions from both traditional donors and South–South cooperation providers. The extent to which these goals have been achieved, however, remains limited. Transparency has been undermined by ambiguous eligibility criteria in some components; and the inclusion of mobilised private resources in an “official” financing metric remains questionable. Nor has TOSSD gained recognition among developing countries as a shared standard, although the United Nations has adopted Pillar 1 as an indicator for monitoring the 2030 Agenda. The fact that TOSSD originated within an exclusive body (the DAC) may have contributed to this outcome. The recent creation of the IFT to monitor the new metric, with membership outside the DAC, is intended as a belated attempt to purge that sin, but it has so far failed to prevent the new platform from being perceived as a creature of the OECD. Designing an integrative metric for a complex cooperation system requires not only robust technical foundations but also legitimacy of origin, something that, in this case, is open to doubt, leading naturally to the question of governance.

7. Governance of the development cooperation system

The aid system originated as an expression of the uncontested hegemony of Western powers. These countries, voluntarily and to a large extent at their own discretion, transferred the resources and knowledge deemed necessary to sustain the progress of developing countries. Underlying this vision was a mix of guilt and arrogance, altruism and power, with an unmistakable neocolonial imprint. As in the colonial experience, the world was divided into two distinct realities – donors an recipient countries – granting the former the status of model to which the latter should aspire. Aid was intended to contribute to this process, serving a homogenising purpose: erasing difference by making “the other” resemble oneself. All of this was supported by the seductive authority of technical language, which assigned to rich countries the knowledge, techniques and resources necessary to foster the progress of the Global South (Ferguson, 1994).

This vision was translated into a system whose governance was controlled by donors. This was not always the case. The initial steps towards building an international development cooperation system assigned a central role to multilateral action, particularly to the United Nations. This vision was reflected in the creation of the FAO in 1944 to combat hunger; the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development in 1944 to finance investment projects; the United Nations Expanded Programme of Technical Assistance, approved in 1945 (and launched in 1949), to fund projects; the United Nations Special Fund in 1957 to support assistance to developing countries; and IDA in 1960, within the World Bank, with a similar mandate and partly to diminish the Special Fund’s prominence.

However, the intensification of the cold war and the triumph of the Cuban Revolution led the United States – and, with it, other donors – to strengthen their control over international aid, aligning it more closely with their national strategic interests by creating or reinforcing institutions responsible for its management. This was the origin of the first national development agencies and, in 1960, of the Development Assistance Group (DAG) within what would later become the OECD. The DAG was the precursor to the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), a donor-controlled coordination body which, from the 1960s onwards, became the central hub of international aid system governance, displacing the United Nations. Accordingly, bilateral flows came to dominate multilateral flows.

Throughout its history, the DAC has played a major role in improving ODA reporting and standard setting. However, the world has changed, and development cooperation is no longer the exclusive domain of rich countries. A large number of developing countries – many of which are not DAC members (and are unlikely to become so) – now pursue their own development cooperation policies. Many already play, or are poised to play, a growing role in development finance and bring with them distinct cooperation models. It is therefore necessary to define a governance framework for the cooperation system that accommodates and represents this diversity. Owing to its technical capacity and experience, the DAC should be part of this framework, but it clearly cannot provide the sought-after solution, given the selective nature of its membership. Nor is the more open and inclusive Development Cooperation Forum (DCF) a viable alternative in its current form.

Thus, none of the existing dialogue and coordination platforms meet the requirements of effectiveness, inclusiveness, legitimacy and transparency needed for sound global governance. The OECD DAC is effective but unrepresentative; the UN’s Development Cooperation Forum is inclusive but lacks the mandate and capacity to set and enforce standards; the Global Partnership is weak and narrowly focused on the aid effectiveness agenda; and the recently created International Forum on TOSSD is limited to the scope of that new metric. It is difficult to envisage an institutional solution that would replace or supersede these bodies.

For this reason, a more realistic approach would be to advance from the current institutional landscape towards improved global governance, necessarily anchored in the United Nations. One possible pathway would involve establishing joint work programmes between existing platforms, particularly between the DCF and DAC, on metrics, standards, and eligibility and graduation criteria that go beyond per capita income. In parallel, steps should be taken to strengthen the role of the United Nations in governance, potentially through an interagency programme (including UNDESA, UNCTAD, UNDP, OCHA and the World Bank, among others) to support this process of convergence, while promoting some form of intergovernmental dialogue on the subject.

8. Closing remarks

We have started from the premise that aid is undergoing a constitutive crisis. Beyond adverse circumstances – such as the neoconservative offensive and budgetary adjustments – the issue at stake is the system’s capacity to respond to the transformations that have taken place in international structures, market realities and development experience.

In the deliberative exercise undertaken in these pages, three possible models emerge towards which reform could be directed. These are ideal types in the Weberian sense – not intended to reflect reality, but to provide reference points for clarification. Common to all three should be progress towards the decolonisation of the cooperation system, in order to establish relations on a more balanced footing in the distribution of voice and opportunities in the international system, with due respect for the identity and value criteria for progress specific to each society. Achieving such balance is difficult in a system grounded in asymmetries of resources and capacities among countries. Advancing along this path therefore requires taking steps – however modest – towards a system in which both rights and obligations are recognised by all countries, and binding commitments can be established. One route towards this would be to strengthen a reformed multilateral framework (currently in a deep crisis) and define some form of financing linked to globally agreed tax instruments. The most comprehensive reform of the development financing system is therefore part of the task ahead.

Beyond this shared element, the models differ in their basic features (Table 2). The most accessible and straightforward option is the focused model, which rests on a narrower definition of eligible recipient countries and a streamlined agenda prioritising humanitarian assistance and the fight against extreme poverty. Moving towards this model would require donors to agree on resource allocation criteria that ensure the intended targeting and foster coordination among them. This approach could advance through incremental reforms of the current aid system, without major changes to its governance structure. The foundation of this model lies in the universal recognition of obligations of relief and assistance – at the core of the law of peoples (Rawls, 1999) – and its narrative is the most widely supported and easily understood by the public (Kumar et al., 2025). Its advantage lies in the pursuit of maximum impact from limited resources by channelling them to where they are most needed; its drawback is that it entails renouncing a more comprehensive and transformative development agenda, leaving many countries without support.

The second option involves moving towards a model in which cooperation focuses on shared challenges, contributing to the provision of those international public goods most critical for sustainable development. This entails a significant change in the logic of the cooperation system, from a redistributive agenda to one aimed at correcting externalities. While this agenda is better understood in academic circles than by the general public, the principle of pursuing common challenges and interests provides a strong narrative.8 Given the scope of IPGs, moving towards this model would require going beyond the scope of ODA, giving greater prominence to multilateral (regional or global) bodies; conversely, national development agencies would lose functionality in favour of the various ministerial departments concerned. A disadvantage of this approach is the relegation of distributive components – essential to the development agenda – which may not be adequately addressed within an IPG-focused framework.

Finally, the third option is the most complex and demands the most substantial reform effort, but in return it offers cooperation the broadest scope and the greatest transformative ambition. This shared model assumes that the function of cooperation is to accompany countries in their transformation processes, taking into account their diverse needs, thus requiring the management of complexity and diversity. It demands resources from multiple sources (with varying degrees of concessionality) and pursues a plurality of objectives: from covering basic needs in the most disadvantaged contexts to acting as a catalyst for change in more advanced settings. To fulfil this role, the system must be open to contributions from all countries according to their capacities, even if not all are potential resource recipients, and must move towards identifying financing sources based on global taxation mechanisms. ODA could continue to exist as a specific policy of OECD donors, but within a broader framework of agreements that reconciles shared minimum standards with rules differentiated according to countries’ capacities.

The effectiveness of this model requires granting the multilateral system a greater role in managing cooperation, while preserving a significant – though smaller – share for bilateral action, enabling countries to express affinities and transfer experiences directly. It assumes that development action should encompass the four agendas currently present in cooperation and recognise the ethical foundations of each: moral duty, moral responsibility, common interest and mutual interest (Chatterjee, 2004). This system calls for inclusive and representative governance, which in the future must be anchored in the United Nations.

References

Ahmed, M., Calleja, R. & Jacquet, P. (Eds) (2025). The future of official development assistance. Incremental improvements or radical reforms?, Washington, Center for Global Development, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/future-official-development-assistance-incremental-improvements-or-radical-reform.pdf.

Alonso, J.A. (2025). La ayuda internacional: hacia la renovación o la progresiva irrelevancia, Información Comercial Española, 939, pp. 149–167

Alonso, J.A. (2024). El nuevo rostro de la economía del desarrollo, Información Comercial Española, 934, pp. 9–30

Alonso, J. A. (2012). From aid to global development policy, DESA Working Papers No. 121. Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Alonso, J.A. & Glennie, J. (2016). What is development cooperation?, Development Cooperation Form Policy Brief 1, https://www.effectivecooperation.org/sites/default/files/documents/2016_dcf_policy_brief_no.1.pdf.

Alonso, J.A & Gutiérrez, R. (2025). Pathologies of inequality in Latin America. Challenges and consequences, Berlin, De Gruyter

Aly, H., Gulrajani, N. and Pudussery, J. (2024) Dialogue #1: Crafting a new rationale for northern donorship. Donors in a post-aid world series. London: ODI Global https://odi.org/en/publications/dialogue-1-crafting-a-new-rationale-for-northern-donorship/.

Bracho, G. (2017). The Troubled Relationship of the Emerging Powers and the Effective Development Cooperation Agenda. DIE Discussion Paper 25/2017.: https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/DP_25.2017.pdf

Bracho G. (2025). In search for metrics in a Post-North-South international development cooperation agenda, in Ahmed et al., 2025

Calleja, R., Cichocka, B. Gavas, M. & Pleek, S. (2022). A global development paradigm for a World in crisis, Washington, CGD Policy Paper 275, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/global-development-paradigm-world-crisis.pdf.

Chatterjee, D.K. (edit) (2004). The ethics of assistance. Morality and the distant needy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Craviotto, N. (2023). Aid under threat. The shadowy business of private sector instruments. Eurodad. https://www.eurodad.org/aid_under_threat.

DAC (2025): Cuts in official development assistance: OECD projections for 2025 and the near term, Policy Brief, June, https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/06/cuts-in-official-development-assistance_e161f0c5/8c530629-en.pdf

Elgar, K., Ahmad, Y., Bejraoui, A., Carey, E., Choudhury, M., De Paepe, G. (2023), The role of development co-operation in the provision of global public goods, OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers, No. 111, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Ferguson, J. (1994). The Anti-Politics Machine. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Glennie, J. (2020): The future of aid. Global Public Investment, London, Routledge.

Glennie, J. (2025): The birth of global public investment. Mutual interest and mutuality in 21st century international public finance, Global Cooperation Institute.

Gulrajani, N. (2022). Development narratives in a post-aid era. Reflections on implications for the development effectiveness agenda, UNU-WIDER Working Paper 2022/149.

Hackenesch, C., Hogl, M., Ohler, H. & Burni, A. (2022) Populist Radical Right Parties’ Impact on European Foreign Aid Spending Journal of Common Market Studies 60(5): 1391–1415 https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13308.

Hulme, D (2016). Should rich nations help the poor? Cambridge, Polity Press.

Kenny, Ch., & Yang, G. (2021). Why do some donors give more aid to poor countries? Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/why-do-some-donors-give-more-aid-poor-countries.

Kharas, H. & Rogerson, A. (2012). Horizon 2025. Creative destruction in the aid industry, ODI Report, London, ODI.

Kharas, H. & Rogerson, A. (2017). Global development trends and challenges. Horizon 2025 revisited. ODI Report, London, ODI.

Kharas, H., Makino, K. & Jung, W. (2011). Catalyzing development. A new vision for aid. Washington, Brookings Institution.

Kligebiel, S. & Sumner, A. (2025): Four futures for a global development cooperation system in flux. Policy at the intersection of geopolitics, norm contestation and institutional shift, IDOS Policy Brief 11/2025.

Klingebiel, S., Mahn, T. & Negre, M. (2016). The fragmentation of aid: concepts, measurements and implications for development cooperation, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Kumar, C., Hargrave, K., Craviotto, N. & Pudussery, J (2025). The case for development. Exploring new narratives for aid in the context of the EU’s new strategic agenda, ODI Europe Research Report. https://media.odi.org/documents/Full_Report_The_Case_for_Development.pdf.

Lopes, C. (2024): The self-deception trap. Exploring the economic dimensions of charity dependency within Africa-Europe relations, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Martens, B., Mummert, U., Murrell, P. & Seabright, P. (2008). Institutional economics of foreign aid, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Mawdsley, E. (2012): From recipients to donors. Emerging powers and the changing development landscape, London, Zed Books.

Melonio, Th., Jean-David Naudet, J-D. & Rioux, R. (2024) Double Standards in Financing for Development. AFD Policy Paper No. 14. Agence Française de Développement, 2024. www.afd.fr/en/ressources/double-standards-financing-development.

Myrdal, G. (1970). The challenge of world poverty. A world anti-poverty program in outline, New York, Vintage Books.

Myrdal, G. (1957), Economic theory and underdeveloped regions, London, Duckworth.

Nurkse, R. (1953). Problems of capital formation in underdeveloped countries, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Pinyol-Jiménez, G. (2025). La securitización de la política de emigración y asilo de la Unión Europea, (199-2024). Una aproximación desde la Escuela de Copenhague, Valencia, Editorial Tirant lo Blanch.

Rawls, J. (1999). The law of peoples, Cambridge Mass, Harvard University Press.

Ritchie, E. (2020). New DAC Rules on Debt Relief – A Poor Measure of Donor Effort CGD Working Paper No. 553. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/new-dac-rules-debt-relief-poor-measure-donor-effort.

Rodrik, D. (2007). One economy, many recipes. Globalization, institutions, and economic growth, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Rosenstein-Rodan, P. (1943). Problems of Industrialization of Eastern and South- Eastern Europe, Economic Journal v 53, No. 210/211, (1943), pp. 202–11

Santander, G. & Alonso, J.A. (2017). Perceptions, identities and interests in South-South cooperation: the cases of Chile, Venezuela and Brazil, Third World Quarterly, 39 (10), 1923–1940.

Severino, J-M. & Ray, O. (2009). The End of ODA: Death and Rebirth of a Global Public Policy CGD Working Paper 167. Center for Global Development.

Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.

Sumner, A. & Mullett, R. (2013). The future of foreign aid. Development cooperation and the new geography of global poverty, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Weber, M. (2017). Methodology of social sciences, London, Routledge.

World Bank (2021): A changing landscape. Trends in official financial flows and the aid architecture, Washington, The World Bank

Ziai, A. (2016). Development discourse and global history. From colonialism to the sustainable development goals, New York, Routledge.

Notas:

1- A definition of development cooperation is provided by Alonso and Glennie (2016). Within this framework, ODA represents one component of the broader cooperation system, structuring the contributions of traditional donors in line with the accounting standards established by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC).

2- Klingebiel and Sumner (2025) propose a classification of aid system reforms based on the taxonomy of evolutionary institutional change developed by Streeck & Thelen (2005). Yet the model that most accurately captures this process is that of high institutional stickiness (Alonso & Gutiérrez, 2025).

3- See https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

4- See Maddison Project Database 2023: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2023

5- Although the more common term is global public goods (GPGs), this study will instead refer to them as international public goods (IPGs), as some do not reach a truly global level: they may be regional public goods or simply cross-border in nature.

8- We distinguish between “common interests” that affect goods whose benefits are non-excludable public goods, and “mutual interest”, which refers to the area of convergence between the interests of the provider and recipient of cooperation.

Keywords: development cooperation, official development assistance, multilateralism, emerging countries, global poverty, global public goods, humanitarian aid

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/docCIDOB.2025.18.2/en

E-ISSN: 2339-9570