European enlargement: time to find alternatives to a herculean task

The desire to enlarge the European Union (EU) for geopolitical reasons in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine ignores both the causes behind the stagnation of the accession process in the last decade and the extraordinary challenges enlargement would present to the bloc and its member states.

Alternatives to enlargement are needed to prevent frustration among the candidate countries and facilitate their security, economic development and adherence to European values.

Differentiated integration could serve as a transition phase until the EU carries out internal reforms that are vital if it is to accommodate new members.

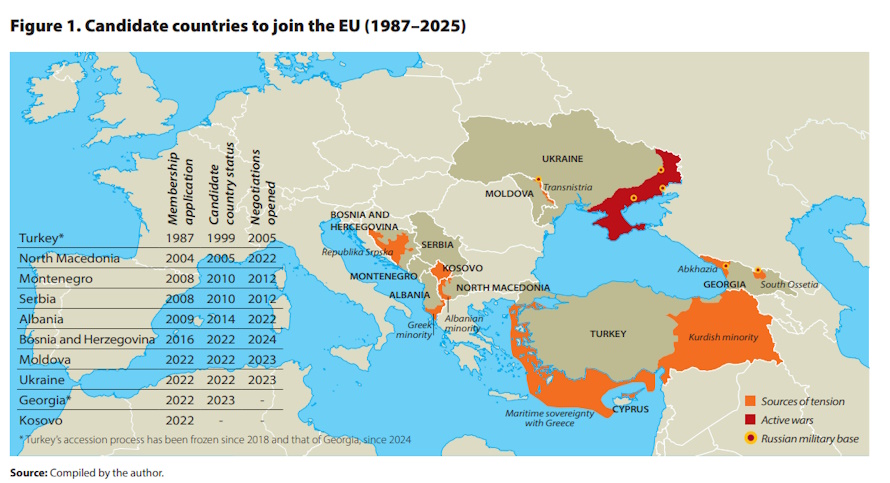

The European Union (EU) is at a crossroads. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has triggered a shift in European thinking and quickened the pace of an enlargement process in the doldrums over the last two decades. In 2022, Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia – three countries that belong to the Eastern Partnership (EaP) and which are not in full control of their territory – submitted applications to join the European club, along with Kosovo. That same year, the EU granted candidate status to the first three, as well as to Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had applied for membership six years earlier. It also formally opened accession negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania (candidates since 2005 and 2014, respectively) even though the latter country failed to meet the required conditions. In 2023, the EU began talks with Ukraine and Moldova too, in the record time of less than two years after the two countries had applied for accession. According to the European Commission (EC) president, Ursula von der Leyen, Ukraine could join the EU before 2030 as it would be the surest guarantee of its security. In the view of the European commissioner for enlargement, Marta Kos, Ukraine’s accession is a priority and should happen before the other nine candidates countries join, even if some have been carrying out reforms for two decades in order to comply with the EU acquis (acquis communautaire).

This geopolitical logic, which is what lies behind the revival of the EU enlargement processes, stands in contrast to the logic of modernisation and stability underpinning the accession criteria established in Copenhagen in 1993; it also passes over the reasons for the stagnation of European enlargement after 2007. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the EU signed the Europe Agreements with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe which, after nearly 14 years of negotiations and reforms, gave rise to the great enlargement of 2004 (Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia). It was completed in 2007 with the incorporation of Bulgaria and Romania, the two “laggard” applicants in the fulfilment of the accession criteria. This “big bang”, as the enlargement into Eastern Europe is commonly known, was possible thanks to a favourable geopolitical context facilitated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, a pro-enlargement outlook on the part of the European public and elites, and an overall tendency towards democratisation that was very much to the fore in the candidate countries.

The global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis of 2010–2012 marked a turning point, as they raised doubts about the European liberal model as a driver of prosperity. Against this backdrop, the rise of Euroscepticism, nationalism and democratic backsliding, coupled with an increase in bilateral conflicts and Russia’s greater assertiveness, helped to slow enlargement. In this period only Croatia joined the EU, in 2013, after overcoming stricter conditions laid down in the “renewed consensus on enlargement” adopted in 2006. Over the last decade, the talks with the Balkan candidate countries (Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia) have moved at a snail’s pace, and the negotiations with Turkey were officially frozen in 2018.

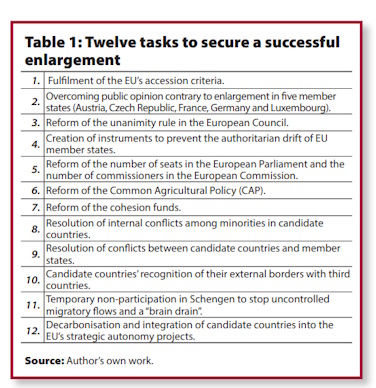

At present, in its geopolitical awakening, the EU has opted to frantically reactivate its prime instrument of regional influence – access to the European club – rather than explore other association alternatives. By doing so, and proposing accelerated integration timeframes, the EU is ignoring the scale of the changes required to bring it to fruition. These changes are fundamental, both on the level of the functioning of the EU and within the candidate countries. It is without question a herculean task (see Table 1). It not just about the candidate countries meeting the accession criteria, but about changing European public opinion that has turned against enlargement. The enlarged EU must also be governable, which will require far-reaching reforms of its governance and budget as well as ensuring the stability and security of its borders.

Main challenges for EU enlargement

Public opinion and governance

Unanimity in the European Council is the keystone of the accession process. It is required in order to grant candidate status, start negotiations, open or close negotiation chapters and to approve the accession treaty. The treaty must then be ratified by all the contracting states, including the candidate country, in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements, be it parliamentary ratification or by referendum.

According to the latest Eurobarometer data (October–November 2024), however, nearly 60% of the public in Austria and over 50% of the people in France, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic and Germany are opposed to an enlargement of the EU. The main concerns are that enlargement will further complicate decision-making at the European level (a feeling shared in political circles); it will increase instability and the lack of security; and, to a lesser extent, the impact it might have on the labour market. In addition, judging by the election results and political landscape in countries like France, Germany, Italy and Austria, it is likely that the domestic political context in those countries will become even less receptive to enlargement in the coming months and years.

In the candidate countries, support for European integration has stalled on account of disenchantment with the long accession process and these countries’ internal dynamics. In October 2024, in the referendum in Moldova to ratify citizens’ desire to belong to the EU, the “yes” option won by a nose with 50.46% of the ballot and thanks to the diaspora vote. In Serbia and North Macedonia, most people believe their country will never join the EU. While they are more positive in Kosovo and Albania and a large majority expect accession to happen before 2035, public opinion there appears to have little sense of the mood in Austria, Germany, France, Poland, Romania or Denmark, where the population that rejects enlargement of these countries almost doubles those in favour.

It is no small matter if enlargement makes decision-making more difficult at the European level. The EU lacks effective tools to tackle the authoritarian drift of member states. The collective decision-making process and the principle of unanimity in the European Council in key areas such as foreign policy or approving the European budget, for example, make it all too easy for issues to be hijacked by national interests. On top of that is the necessary reform of the allocation of seats in the European Parliament, as well as the reduction of the number of commissioners in the EC, which currently stands at one per country.

Besides, meeting EU accession criteria is not always a guarantee that democracy has taken root. The top-down nature of conditionality in the accession process limits processes of scrutiny and internal criticism, while the formal advance of talks can serve to legitimise corrupt elites. Once in the EU, countries have little incentive to maintain their adherence to European liberal values, as evidenced by cases such as Hungary and Poland, which have seen an erosion of judicial independence and restrictions on press freedom.

At present, every candidate country is considered a flawed democracy, a hybrid regime or partially free according to the governance indicators devised by institutions like The Economist or Freedom House. While most have made progress over the last decade, the progress has not been across the board. Countries such as Moldova and Ukraine have reported notable advances in terms of transparency in democratic processes, policy effectiveness and regulatory quality, but they are still at low levels, and protection of the rights of minorities is wanting. Turkey, Georgia and Serbia, for their part, have seen declines in their rule of law and democratic quality which, in part, has led to the freezing of the accession processes of the first two countries and a de facto freeze on Serbia’s integration.

As for Europeans’ perception regarding a possible increase in instability and lack of security as a result of enlargement, the data on violence inside the candidate countries shows disparate trends. Levels of violence, armed conflict and political instability are particularly high in Ukraine and Moldova, and they have increased significantly in Montenegro. Also, Ukraine, Serbia and Montenegro feature among the five European countries with the highest crime rates. And, if not tackled proactively, the end of the war in Ukraine could trigger a substantial leakage of weapons from the conflict zone into other countries. With Ukraine’s accession to the EU, the free movement of goods would facilitate the proliferation of illegal weapons in the bloc’s territory.

Economic impact

In terms of economic size, the nine candidate countries from the Balkans and the EaP – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, plus Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, respectively – barely represent 2.5% of the EU’s GDP, which means in principle their integration should not be a problem. The challenge, however, is in terms of sector composition, population and the economic gap in relation to the European average, which would have a profound impact on the EU budget.

First, in every candidate country the primary sector carries more weight than in the EU as a whole, a difference that is especially significant in the case of Ukraine. Given its size, this country would increase Europe’s arable land by 30%, making it the EU’s biggest agricultural producer and the main recipient of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funds. Different studies estimate that agricultural payments to Ukraine in the next European budget1 would come to between €50bn and €100bn, while the payments to the rest of the candidate countries (not counting Turkey) would amount to as much as another €30bn euros. To offset the new expenditures a European Parliament study from January 2025 proposes cutting agricultural payments to the current member states by 15%. Alternatively, it suggests reforming the CAP and requiring specific commitments from the candidates, as has been the case in previous enlargements. This, however, is very touchy subject, politically speaking, since European farmers have repeatedly shown their power of mobilisation and their aversion to seeing their interests harmed, as evidenced by the protests against the entry of Ukrainian grain and the subsequent introduction of restrictions on the part of the EC.

Second, there is a significant gap between the per capita income of the candidate countries and that of the member states. This could lead to the current candidates (not including Turkey) taking as much as 15% of the cohesion funds in the next EU budget. The new EU members would reduce the average gross national income per capita, meaning that some of the currently “less developed” regions of the EU would become “transition regions” and others would be reclassified as “more developed regions”, limiting their access to the cohesion funds. Here, different estimates put the potential cohesion payments at between €30bn and €60bn, and up to €30bn extra for the candidate countries from the Balkans and the EaP. Specifically, it is calculated that financing the enlargement would require a reduction of nearly 20% in the funds allocated to Italy, Portugal and Malta, and a decrease above 10% for Hungary, Spain and Finland. According to the European Parliament study, 15 member states could see their cohesion policy allocation cut by 24% following enlargement.

Third, it is worth pointing out that that the overall impact of enlargement on the EU budget would exceed the amount mentioned from the CAP and cohesion fund payments, since the budget has other items too. Estimates on the total impact of enlargement on the European budget for 2028–2035 place it at between €70bn and €140bn, in the case of Ukraine, and a further €44bn for the rest of the candidate countries (excluding Turkey). This is not counting military expenditure for the protection of these countries or the cost of rebuilding Ukraine, which in early 2024 the World Bank already calculated at €453bn. While there is no consensus on whether the member states that are currently net recipients from the European budget will become net contributors as a result of enlargement (that is, they will give more than they receive), it is naive to think that budget matters will be no great obstacle to the members states accepting the entry of new partners.

By way of a solution, consideration could be given to increasing the European budget to furnish the EU with better tools that can back up its geopolitical ambition. Amid the debate over the next multiannual financial framework, however, Germany and others reject both increasing the European budget by more than 1% of the EU’s gross national income and refinancing the Next Generation funds (0.7% of GDP). The disinclination to rise to common challenges with a common budget is clearly visible in defence spending, which after becoming Europe’s new high priority will be funded primarily through national budgets.

Previous enlargement processes gave rise to rapid growth in the candidate countries, but this was mainly due to the structural reforms that had taken place before accession, and to the subsequent improvement in their access to capital markets. But if the EU speeds up the accession of the new candidate countries on geopolitical grounds, it is highly likely that the post-accession economic boost will be more limited, as the momentum of reform slows significantly when countries are actually part of the EU. As for capital flows, let the experience of countries like Romania and Bulgaria serve as an example. While they saw an extraordinary rise in foreign direct investment (FDI) following EU accession, they have remained at pre-accession levels ever since.

Lastly, it is important to point out the demographic impact of enlargement. Ukraine would increase the EU’s population by 10% and become the bloc’s fifth most populous country; the rest of the candidates from the Balkans and the EaP would add another 5%. Given the social and political tension over migration in most European countries, together with concern in the Balkans about a “brain drain”,2 it is foreseeable that access to the Schengen area will be restricted for the new members as a condition for accession, as already occurred when Romania and Bulgaria joined. For a transitional period after the accession of new member states, European legislation allows for certain conditions to be put in place that limit the free movement of workers from these states.

In conclusion, EU enlargement, especially if it includes Ukraine, must be accompanied by a profound restructuring of the European budget, particularly as far as the CAP is concerned, which will be very hard to accomplish. The candidate countries, on the other hand, should not expect economic miracles in the wake of accession, all the more so if this is not accompanied by strict prior conditionality and a lengthy period of reforms.

Security and strategic autonomy

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is without doubt the primary reason for speeding up the EU enlargement process, with security now European leaders’ main concern. Out of the candidates, only the incorporation of Turkey and Ukraine would significantly increase the EU’s military capabilities. Before 2022, Ukraine already had the third biggest army in Europe, behind only Russia and Turkey, and a large number of soldiers relative to its population. On the other hand, all the countries expect the EU to act as a guarantor of their security, in accordance with the mutual defence clause (Article 42.7 TFEU) which stipulates that “if a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power”. This clause specifies “by all the means in their power” and is therefore much more precise and binding than the vague wording of the famous Article 5 of NATO which states that members “will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force”.

Any conflict in Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine or a Balkan country, then, could inevitably drag the rest of the EU countries into an armed confrontation. Hence the requirement, until now, that if a country is to join the EU it must have no territorial disputes with its neighbours.3 The new geopolitical logic of enlargement, however, passes over this issue and places the emphasis on the military capabilities that Ukraine could bring to the EU and the strategic depth that the new members would provide to the defence of Central Europe.

At present, peace and stability are not assured in most of the candidate countries. In the case of the three EaP applicants, not one of them is in full control of their territory. In Ukraine, it is hard to envision a scenario of peace and acceptance of borders with Russia that does not give rise to further disputes in the future. In Georgia, the government is not in control of Abkhazia or South Ossetia, two territories that Russia recognises as independent. In the event of a conflict in Georgia, only one motorway – within range of Russian artillery in Ossetia – connects the Black Sea and Turkey with Tbilisi, the capital, which is over 4,000 km from Brussels. In Moldova, the region of Transnistria hosts Russian military bases and in the region of Gagauzia 95% of the population voted against Moldova joining the EU in last year’s referendum. Serbia and Kosovo, for their part, have still to settle their differences, and in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina the Bosnian prosecutor’s office has ordered the arrest of the pro-Serbian leader of Republika Srpska for moving towards the independence of the territory. Over the last few years, Macedonia has changed its name to North Macedonia; it has altered its constitution to satisfy the cultural and linguistic demands of Bulgaria; and it has improved the integration of its Albanian minority following the armed conflict with members of this community in 2001. Even so, there are nagging doubts in the country over whether these changes will be enough to join the EU club, particularly given the surge in nationalist and Eurosceptic forces.

Bilateral conflicts not only exist between candidates or between these applicants and third countries; several still maintain disputes with member states, as in the cases of Hungary, Romania or Greece. The far-right winner of the first round of the presidential elections in Romania, Călin Georgescu, for example, claimed Romanian sovereignty over territories currently in Ukraine and Moldova. In 2023, Greece threatened to block Albanian accession, mainly over the maritime disputes between the two states. The root of these disputes lies in ethnic divisions and rights claims on the part of minorities, who are often highly concentrated geographically and can influence geopolitical dynamics despite representing only a small percentage of the population. On top of that is that fact that in three of the candidate countries – Turkey, Albania and Kosovo – Muslims are in the majority and in another two – North Macedonia and Bosnia – over 40% of the population belongs to that community. This is unprecedented in the EU, in whose member states the majority of the population lean toward secularism or Christianity.

Nevertheless, the accession of new members could enhance the EU’s strategic autonomy, since some Balkan countries and Ukraine hold significant reserves of strategic raw materials that would be useful for improving the bloc’s supply chain resilience. Ukraine in particular is a major global supplier of titanium and a potential source of over 20 critical raw materials for the EU. Exploiting them, however, should be treated with caution given the recent environmental protests seen in the Balkans, prominent among which, for example, is the public opposition to lithium mining in Jadar (Serbia), a project classified as strategic by the European Commission. The case of Ukraine, moreover, shows that even when there is a political agreement between the EU and its partners, putting it into practice is sometimes very tricky. Ukraine and the EU signed a Strategic Partnership on Critical Minerals in 2021, with a view to reaching goals such as supplying 10% of Europe’s graphite consumption in 2030. But the war and the dearth of European mining companies have so far prevented the deal from bearing fruit, while the critical minerals deal struck between the United States and Ukraine casts doubts on the EU’s access to those Ukrainian minerals in the future.

Lastly, most candidates except Albania are highly dependent on coal for energy production, and that clashes with European guidelines and climate commitments. The Balkans typically face high energy costs and power cuts, which means they will hardly bring stability to the European grid. As for Moldova and Georgia, the two states have some of the lowest energy self-sufficiency rates in the world, and in Ukraine’s case its energy system has been severely damaged by constant Russian attacks.

To sum up, out of all the candidate countries only Ukraine would increase the EU’s military power, though that would entail the risk of embroiling the rest of the countries in an armed conflict under Article 42.7 TFEU. Besides, while the EU’s strategic autonomy could be bolstered thanks to the candidate countries’ critical raw materials reserves, exploiting them will not be easy and nor does it hang on these countries belonging to the single market.

Alternatives to enlargement

The EU has decided to employ its go-to toolbox from the 20th century (enlargement policy) to address 21st century problems, particularly the Russian challenge and the growth in influence of third actors in its immediate neighbourhood. There are, however, other simpler mechanisms for promoting peace, prosperity and democracy in the region, without having to tackle a highly complex reform of the EU.

The EU is the main trading partner of all the candidate countries except Georgia, because of its geographical location. Moldova and Ukraine have become more dependent on EU trade over the last decade, even though they are not part of the single market. Trade in services with Ukraine, for example, is growing thanks to an agreement (the DCFTA) that establishes a principle of no discrimination. This clause does not feature in the Stabilisation and Association Agreements between the EU and the Western Balkans, and it restricts trade growth with these countries.

The EU is also a key player in FDI flows into the Western Balkans and the EaP, but they are only increasingly significantly in Ukraine and North Macedonia. Sanctions and geostrategic changes in countries such as Montenegro mean that Russian investments in the region are shrinking. Brussels’ concern is focused on China’s growing presence in countries like Serbia and Montenegro, which could have a negative impact on the development of the rule of law and democracy. Yet these countries’ membership of the EU would not resolve this dilemma, as other European countries such as Hungary also report high rates of Chinese investment.

As an alternative, we have the differentiated integration model that is already being applied successfully in the EU. The eurozone group, for example, is comprised of just 21 EU countries; the Schengen area is made up of 25 EU countries plus four from the European Free Trade Association (EFTA); and there are other initiatives formed by states that come together in coalitions to further specific goals, such as defence. Regarding partners from outside the EU, a strategic association agreement with Canada has been signed recently which includes geopolitical alignment and unprecedented cooperation on trade, investment, the digital space, raw materials, security and defence. In this last area, the EU has agreed to the participation of Ukraine, the United Kingdom and EFTA states in the new European joint weapons procurement instrument Security Action for Europe (SAFE). In short, deepening strategic ties with the European partners and like-minded states does not require enlargement.

A geopolitical logic will not resolve the problems of enlargement. Repeating promises of fast-tracked accession may give rise to frustration among the candidate countries and lead them to seek alternative partners, as has occurred in the candidate countries from the Western Balkans over the last decade. Instead, consideration should be given to flexible integration mechanisms that allow varying levels of participation in EU policies and institutions. Differentiated integration could serve as a transition phase until the EU carries out the internal reforms, particularly those relating to governance and the European budget, which are essential if it is to accommodate new members. The EU should adapt its transition proposals to the levels of preparation, the degree of compliance with EU norms and the agency of the candidate countries.

Notes:

1- Multiannual Financial Framework 2028–2034.

2- Business surveys in the Balkans list it as the main concern.

3- The EU partly ignored this requirement in the case of Cyprus because its dispute over the occupation of the north of the island and maritime borders was with Turkey, a candidate to join the EU and a member of NATO.

E-ISSN: 2013-4428

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24241/NotesInt.2025/321/en

All the publications express the opinions of their individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of CIDOB or its donors

Translation from the original in Spanish: Richard Preston