The EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive and corporate narrative disclosure practices: the case of the fashion industry

Documents CIDOB: 10

Winner of the 21st Century Europe Talent Award, launched by CIDOB and Banco Sabadell Foundation in collaboration with Fundació Catalunya Europa, in the framework of Programa Talent Global.

The present work tackles the crucial issue of global sustainability and the challenge of policy coherence around sustainability, focusing on sustainability reporting in the fashion industry in the EU. As the legislative framework has grown increasingly rigorous, so has the importance of well-formed and carefully focused legislation. By examining non-financial (sustainability) reporting in the fashion industry and its challenges, this paper exposes the most plausible next steps to be taken in terms of requirements for non-financial reporting as well as changes to corporate purpose and behaviour. This paper engages with policy and legal considerations, practical behaviour and their analysis in relation to sustainability science, providing an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary understanding of the sustainability reporting and adjacent framework in the EU.

1- Introduction

The shift in the narrative of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to one of sustainability has not been adequately reflected in business conduct. In reality, weak sustainability practices that produce similar results to CSR practices have often continued, and there has been a failure to incorporate strongly more sustainable practices that would cause an organic business change that is reflected in all corporate operations and departments and minimise negative environmental and social impacts. In the EU, the most relevant mandatory regulation for distinguishing between weakly and strongly sustainable corporate practices regulates corporate reporting of entities with the potential to significantly impact the sustainability of the market as a whole. Sustainability often requires qualitative assessment, as it can prove difficult to determine quantitatively: narrative reports are crucial for understanding corporate sustainability practices and their comparability, especially within a particular sector. To that effect, the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) and the suggested amendments made narrative sustainability reporting compulsory for large corporate legal entities in the EU, including in sectors that are not particularly amendable to sustainability disclosure.

This work focuses on the world’s second-most unsustainable industry – fashion – and analyses reporting practices and their objective transparency, while allowing for a qualitative assessment of their impact on sustainability. Reaching beyond the “one-size-fits-all” approach, the present work differentiates between so-called “fast fashion” companies, luxury brands and sustainable (ethical) fashion. It compares their reporting practices in general and, more specifically, those under the NFRD, in order to critically appraise their approaches to reporting the relevant sustainability data. Relevant and truthful reporting is of crucial importance for informing the market in terms of benchmarking sustainable practices and providing relevant information to consumers. Hence, the analysis of existing practices is indispensable for future policymaking, especially in the light of disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which provides an unprecedented opportunity for industries to move away from “business as usual”. Widespread greenwashing in the fashion industry calls for novel solutions in terms of policymaking and disincentivising the further use of such practices. The insight into the proposed amendments to the NFDR provided by the findings of this paper on the fashion industry can serve as a basis for further research and the amelioration of existing EU policy in the field. Rather than focusing on the purely academic context, the analysis of existing practices gives an important signal for the policy amendments necessary in the field, following the sustainability science requirement of a multifaceted approach that encompasses practical aspects while supporting academic findings and policy advances.

2- The (un)sustainability of the fashion industry

2-1The state of the art

The fashion industry is heterogeneous in nature. Encompassing “fast fashion”, luxury fashion and sustainable fashion (Pedersen and Andersen, 2015), it has gained a reputation for being unsustainable (Arriga, 2015). “Fast fashion” is the name given to low-cost clothing collections that mimic current luxury fashion trends. Its definition in the Cambridge Dictionary shows its inherently unsustainable nature: “clothes that are made and sold cheaply, so that people can buy new things often” (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021). While it thrived pre-COVID-19, the industry is currently struggling: by way of example, the Swedish multinational H&M reported a fall of 90.7% of net benefits in the year 2020, prompting it to close 350 shops globally (H&M Report on Markets and Expansion, 2020). Similarly, the UNCTAD reported a fall in consumer spending on fashion and accessories by 43% in 2020 (UNCTAD, 2020). But the business model of buy–use–dispose and offering several collections per year found another outlet, online sales. Although this could not make up for decreased in-store sales (The Business Research Company, 2020c), it nonetheless allowed the H&M brand to continue existing. Luxury fashion, on the other hand, consists of goods that are not necessary for daily life, but which are sold at elevated prices due to the high quality of the products (Fionda-Douglas and Moore, 2009). While they are not based on mass production and consumption, they bring their own sustainability-related concerns: the destruction of inventory to preserve the value of the brand, human rights violations across their supply chains (Shen et al., 2020) and the use of fur (Ferreira, 2016), amongst other issues. The impact of COVID‑19 on the luxury fashion industry has been especially adverse. With China accounting for 90% of global luxury market growth in 2019, the country’s lockdown severely disrupted the demand side of luxury fashion (Bain and Company, 2020). Almost immediately after, when the virus soared throughout Italy and a national lockdown was imposed there, the supply side suffered severe disruption as many luxury fashion brands are headquartered and have key suppliers in Italy. Sustainable fashion, on the other hand, is an alternative trend that works against unsustainable fashion practices, “encompassing a variety of terms such as organic, green, fair trade, sustainable, slow, eco and so forth, each attempting to highlight or correct a variety of perceived wrongs in the fashion industry” (Cervellon et al., 2010) in terms of their negative environmental and social impact. The design, manufacturing and use philosophy it has formed and the trend towards maintainability seeks to create a system which is sustainable indefinitely (Pencarelli et al., 2020). In terms of the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, sustainable fashion performed better than fast fashion and luxury fashion, experiencing year-on-year decline of 3.24% in 2020 (The Business Research Company, 2020b), as compared to 12.32% for fast fashion (The Business Research Company, 2020c) and around 35% in luxury fashion (McKinsey & Company, 2020). This attests to the fact that social and environmental sustainability ultimately also results in economic sustainability and stability.

Beyond COVID-19’s disruptive impact, the industry had already received a strong demand-side signal that consumers’ focus was shifting away from fast fashion, as shown by several fast fashion company bankruptcies.1 While this is a welcome development, Generation Z currently has a limited impact on the industry’s behaviour given their low purchasing power, meaning additional changes are needed to push the industry towards more sustainable practices. In order for public pressure (e.g. through financial market pressure, reputational pressure and a changed attitude of consumers with significant purchasing power) to be exerted on corporations in the fashion industry, heightened awareness about sustainability challenges needs to be coupled with relevant, comparable, transparent and material corporate reporting on sustainability issues in the industry.

2.2 The fashion industry’s sustainability footprint: where’s the catch?

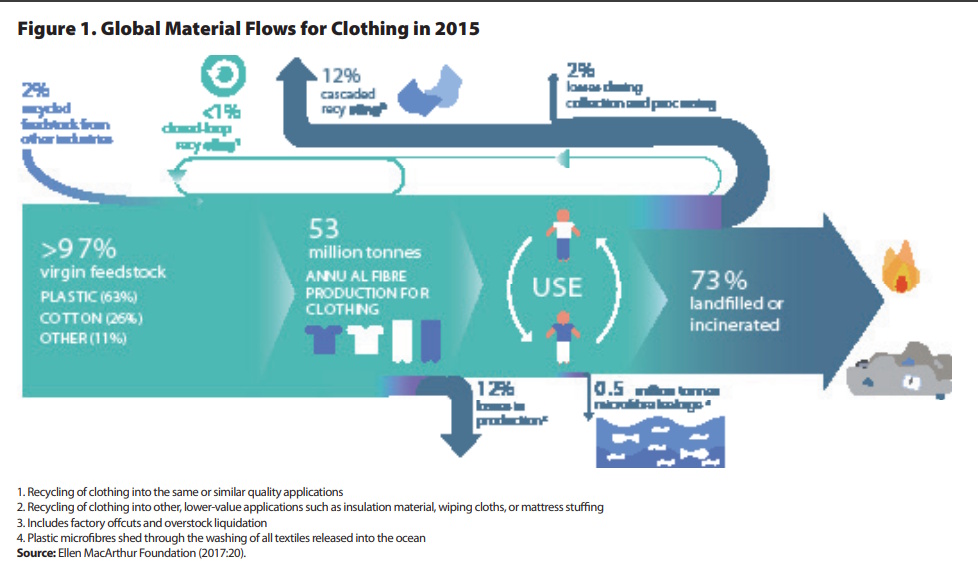

Globalisation brought consumers endless possibilities in terms of available goods. As regards fashion garments, their low price and regularly changing collections prompted consumers to engage in overconsumption (Bick et al., 2018), causing a 400% increase in consumption in the last decade and a significant amount of waste.2 In the last decade, the awareness of the damage caused by the overproduction and overconsumption of fashion garments has risen, increasing the understanding of the hidden costs of cheap clothes: the carbon footprint of the global supply chain (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017); human rights violations throughout the supply chain (German Institute for Human Rights, 2018); water usage and water pollution (Khan and Malik, 2014); and the creation of waste (Jacometti, 2019). While these sustainability challenges have been known about for a long time, the fashion companies have not been systematically addressing them – or reporting on them.

How should we determine what is material in terms of sustainability for the industry as a whole? The scholarly work on the life cycle impact assessment of supply chains in the fashion industry (Bick et al., 2018) and the work of non-governmental organisations on the environmental and social footprint of the fashion industry (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2020) provide a strong basis for deciding the core information fashion companies should disclose – and it is not the proportion of recycled materials they use for their packaging.

The UNEP’s 2020 report on sustainability and circularity in the fashion industry states that the fashion industry’s sustainability hotspots are well established and agreed upon (UNEP, 2020, p.9). It may thus be argued that these are the material issues for disclosure in corporate non-financial annual reports. The most pertinent sustainability hotspots identified in the fashion industry are:3 excessive water use, land use change and deforestation, loss of biodiversity, water pollution, the use of pesticides and fertilisers, CO2 emissions, forced labour, substandard working conditions, below minimum wage, below living wage, child labour, occupational health and safety impacts, gender-related discrimination and violence, excessive working hours, migrant workers (refugees), restrictions on forming or joining a trade union, restrictions on collective bargaining and corruption. In the case of luxury fashion, additional sustainability hotspots (also carrying ethical concerns) noted relate to the materials used (the use of fur, leather and silk as resources) (Karaosman, 2018) and to the non-intense use of the clothing in question. Hence, as a minimum, the material non-financial information that the companies in the fashion industry disclose should include these key sustainability hotspots. But does it? The following section explores the history and critically appraises the development of the NFRD, arguing that there is room for improvement and that such an improvement should necessarily follow the defined sustainability hotspots for the company in question.

3- The development of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive and its applications

3-1 The history and aim of the directive

Since 2018, the NFRD has meant that large companies are obliged by EU law to disclose certain information on the way they operate and manage social and environmental challenges, in an attempt to aid investors, policymakers and other stakeholders to evaluate the non-financial performance of large companies. The directive applies to large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees, which means approximately 6,000 entities – including European fashion companies – are required to engage in non-financial reporting (if they are listed or designated by national authorities as public-interest entities). The directive has been accompanied by two sets of non-binding guidelines: one to ensure corporations report relevant, useful and comparable information and the other to aid companies to report climate-related information and to integrate the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

The NFRD requires large companies to publish reports on their policies regarding environmental protection, social responsibility and treatment of employees, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery, and diversity on company boards (age, gender, educational and professional background). There is flexibility around the format, with companies choosing whichever they consider most useful, using international, European or national guidelines (e.g. the UN Global Compact, the OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises, ISO 26000, etc.), while also considering the EU NFRD guidelines. While the NFRD’s provisions are not very detailed as to the matters to be disclosed, the recitals of the directive are very vocal on the content of the information expected from the companies: “at least environmental matters, social and employee-related matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters” and “a description of the policies, outcomes and risks related to those matters” (NFRD, Recital 6), including “due diligence processes implemented by the undertaking” and, where relevant and appropriate, “its supply and subcontracting chains” (NFRD, Recital 6). Furthermore, in terms of environmental matters it calls for “details of the current and foreseeable impacts of the undertaking’s operations on the environment, and, as appropriate, on health and safety, the use of renewable and/or non-renewable energy, greenhouse gas emissions, water use and air pollution” (NFRD, Recital 7). Likewise, in the field of social and employee-related matters, it calls for “actions taken to ensure gender equality, implementation of fundamental conventions of the International Labour Organisation, working conditions, social dialogue, respect for the right of workers to be informed and consulted, respect for trade union rights, health and safety at work and the dialogue with local communities, and/or the actions taken to ensure the protection and the development of those communities” (NFRD, Recital 7). That information is considered adequate for the most pertinent corporate sustainability issues and should account for their severity in terms of scale and gravity, whether they stem from the corporation’s own activities or are just linked to its operations, products, services and business relationships (including its supply and subcontracting chains). The administrative burdens this could bring to small and medium-sized undertakings are noted. The recitals therefore bring a lot of clarity about the exact aim of the directive, making it somewhat surprising that the non-financial reporting in the EU did not produce relevant information on the sustainability of European businesses beyond what already existed in the market. Coupled with the fact that the NFRD calls upon member states (MS) to ensure enforceability of the directive’s rules and the existence of scientific findings on sustainability hotspots across industries, the modest outcome of the implementation of the NFRD is surprising.

Despite clearly being focused on obtaining relevant information on corporate environmental and social impact, the directive has achieved moderate results, with its revision called for in the framework of the recent EU Green Deal. While the non-financial information to be included has from the beginning been “information to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s development, performance, position and impact of its activity, relating to, as a minimum, environmental, social and employee matters, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery matters[…],” (NFRD, Article 1.1) the non-financial reports have been reporting on the positive environmental and social corporate impact, while refraining from disclosing the information regarding the negative impacts and the planned corporate actions to mitigate those impacts. As The Alliance for Corporate Transparency project noted in its 2018 Research Report, the lack of specification in sufficient detail about what information and key performance indicators should be disclosed led to the situation of a majority of companies acknowledging the importance of environmental and social corporate issues yet not providing clear information in terms of concrete issues, targets and principal risks, which in turn prevents stakeholders from understanding the company’s impact, development, performance and position, as required by the NFRD. Furthermore, in order for the non-financial information disclosed by individual companies to inform on the sustainability of their business, it must also be material, comprehensive and comparable, which is now to be achieved with the revision of the NFRD. By way of example, while corporations disclose some information on the most important environmental issues – such as water use, pollution and waste – they are not considered across the supply chain and corporate operations. Neither are corporations reporting on concrete impacts and their management of those sustainability challenges. Regarding social issues, reports contain information on the number of direct employees, overall gender balance, anti-discrimination policies and health and safety, setting aside outsourced workers and region-sensitive issues. This provides very limited insight into corporate social sustainability, as a substantial portion of corporate operations is outsourced, meaning the sustainability of corporate conduct depends on the sustainability of the practices of suppliers. In fact, transparency on supply chains and audits has been limited. Where companies do report on human rights issues, they express their commitment to human rights protection without giving an account of their human rights due diligence or a clear statement of pertinent challenges and their effective management. Directly contrary to the aim of the NFRD, the reports provide a generalised account of sustainability challenges without applying them to the practices of the company in question.

The NFRD applies a “comply or explain” principle – requiring the company to disclose material information on sustainability-related matters or explain why such a disclosure has not been made. But this does not mean that companies should or will engage in a general non-disclosure, as companies may draw negative publicity that increases their business risks and damages their reputation in the market. It has been shown that, if formulated appropriately, complying with or explaining principles are effective ways to improve corporate behaviour and enhance corporate transparency (Harper Ho, 2017). The lack of clarity on the notion of materiality in the NFRD has also spilled over into national legislation (Jeffwitz and Gregor, 2017) and arguably hampered the quality of non-financial reporting in the European Union. Beyond determining that the NFRD’s materiality is a double materiality (environmental and social materiality that may be financially material), the suggestions of what is to be deemed material do not amount to a firm definition of what is material. For example, while allowing flexibility by calling on corporations to determine the key sustainability-related issues, the guidelines simply re-state the wording of the NFDR and add in the “fair view of the information needed by relevant stakeholders” from the Accounting Directive – albeit calling for consideration to be given to actual situations and sectoral specificities. The Accounting Directive calls for similar information to be deemed material across a specific industry to allow for direct comparison of relevant non-financial disclosures by companies in the same sector. As such, the NFDR and the accompanying guidelines should narrow down the scope of corporate discretion as to what is material in a particular sector. This is currently not the case. What is material remains at the discretion of the company in question, watering down the requirements not to mislead about material information or disclose immaterial information and to clearly distinguish facts from views or interpretations. Furthermore, the NFRD and the accompanying guidelines disregard the possibility not only of underreporting but also of large corporate entities rolling over their sustainability-related commitments and obligations to their suppliers, which are oftentimes small and medium-sized companies. Such behaviour risks sabotaging the aim of the directive not to increase (administrative) burdens for those companies. While the NFRD represents a major first step in the right direction by highlighting the importance of non-financial information disclosure, the NFRD’s implementation in practice shows that there is room for improvement.

3.2 The Impact Assessment: how to approach the revision of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive

In early 2020, the EU Commission issued its Inception Impact Assessment on the revision of the NFRD, allowing citizens and stakeholders to provide feedback on the intended activities. Given the shortcomings of the initial NFRD, the Commission envisaged major enhancements to the existing legal framework as “[t]he demand for better information from investee companies is driven partly by investors needing to better understand financial risks resulting from the sustainability crises we face” and “the NFRD does not adequately respond to these needs” (European Commission Impact Assessment, p. 1). The Commission defined two general groups of issues to be tackled by the NFRD revision: a) the lack of adequate publicly available information on how non-financial and sustainability issues impact companies as well as how companies impact society and the environment;4 b) the incurrence of unnecessary, avoidable costs related to the reporting of non-financial information, also by virtue of different disclosure requirements contained in other EU legislation and the pressure exerted on companies by sustainability rating agencies, data providers and civil society.5 The main objectives of the revision, according to the EU Commission, are threefold: 1) ensuring investor access to adequate corporate non-financial information to allow for accounting for sustainability-related risks, opportunities and impacts in their investment decisions; 2) ensuring that the stakeholders have access to adequate corporate non-financial information to hold the companies accountable for their unsustainability; and 3) reducing unnecessary burdens related to non-financial reporting. All in all, the EU Commission is aiming to ensure that after the revision, the NFRD provides the information to allow unsustainable environmental and social impacts to be understood.

As to the policy options, the Commission laid out the following: 1) continuing with the non-binding guidelines, but revising the already existing guidelines and issuing new guidelines on new topics; 2) exploring the use of standards, endorsing the existing ones or creating new ones; 3) revising and strengthening the provisions of the NFRD by providing more specific detail on the content of non-financial information, requiring the use of a non-financial reporting standard, modifying the scope of the directive, strengthening the provisions regarding the assurance of non-financial information, clarifying and harmonising provisions on where non-financial information should be provided, and strengthening the enforcement regime.

While the first option (revising and issuing guidelines) does not seem to be the most optimal, given the experience with the 2017 and 2019 EU guidelines, the second and third options might provide a better way forward. However, the use of standards on sustainable corporate conduct has also proved to be of limited effectiveness, and they function in a similar manner to the guidelines (Vigneau et al., 2015). As such, the third option seems to be the most optimal, as it allows for a holistic reform of the reporting system, approaching the matter of non-financial reporting from a new perspective. While this might impose additional administrative burdens on companies, in the light of climate emergency as well as the accelerated transformation of sustainability-related risk into financial risks, those burdens are awaiting the companies even in the absence of such a revision of the NFRD. The changing business and environmental reality means that companies need to be aware of their sustainability hotspots in order to be able to include the risks of climate change and other sustainability-related issues in their risk assessment and risk mitigation plan(s). The simplification of operations across the single market is expected to be a positive spill-over effect, helping prevent diverging non-financial reporting requirements at national level and contributing to the long-term resilience of the economy.

Some reservations were expressed about the global competitiveness of EU companies due to these additional costs to which non-EU companies are not currently subject, but calls for sustainability-related disclosure are being made around the world. This situation could be further remedied by extending the scope of the NFRD to entities operating in the EU but based elsewhere.6 A major revision of the NFRD is also expected to have a significant, indirect positive impact on social issues, such as labour standards, non-discrimination and social inclusion through greater capital flows to companies addressing social issues and with good social performance and through the change in the way companies manage related risks in their supply chains.

3.3 Calls for reform

The Inception Impact Assessment drew 78 responses from public and private entities. The majority called for a substantial revision of the NFRD, the limiting of members states’ discretion on the implementation of the directive and strengthening and better defining the corporate reporting obligations, while also imposing those obligations on non-EU entities doing business in the EU.

The responses called for a substantial revision of the NFDR content, essentially introducing a new system of non-financial reporting in the EU. This renewed reporting was envisaged by stakeholders as one that represents maximum harmonisation and/or establishes a Level 1 Regulation in accordance with the Article 114 of the TFEU to prevent diverging national requirements.7

It is interesting to note that none of the responses called for minor changes to EU non-financial reporting. According to the stakeholders that responded, the most important issue to be resolved by the revised NFRD is the issue of policy coherence: ensuring consistency with the EU’s Benchmark Directive, Sustainable Finance Taxonomy and Sustainable Disclosure Regulation, but also incorporating the already developed thematic or sectoral (scientific) findings on sustainability hotspots in the reviewed non-financial reporting framework. More detailed determination of materiality by the EU Commission is called for than has been the case with the guidelines that accompanied the NFRD.

There has also been a call to strengthen enforcement mechanisms and penalties at national level in the form of a strong regulatory mechanism for penalising breaches of duties related to reporting and governance with sanctions for failures to identify, prevent or mitigate risk and impacts or to fulfil reporting requirements that are sufficiently dissuasive and proportionate and applicable to companies and their directors.8 Obviously, for the enforcement mechanisms to be strengthened, the reporting obligations need to be determined in more detail. Ideally, to avoid the generic reporting witnessed in the corporate non-financial reporting based on the NFRD, they should be linked to science-based findings and targets based on what is material in a particular industry.

As the EU Green Deal has brought significant changes to corporate regulation and corporate sustainability obligations, the proposed revision supports and accompanies the shift towards responsible business conduct in the EU. In terms of the fashion industry this means that the reporting should encompass the information on all the identified sustainability hotspots and the accompanying policies for mitigating the negative environmental and social impact of the corporations in the fashion industry. But the business models that are causing the materially adverse environmental and social impacts should also transition towards others that entail sustainable outcomes for the company and society as a whole.

4 - Non-financial reporting in the fashion industry

4.1 The general overview: the obligation of non-financial reporting

Due to consumer pressure and heightened awareness of the negative impact of the fashion industry on the environment as well as society as a whole, fashion companies had already started to engage with sustainability before the NFRD came into force. Unfortunately, the same reproaches apply to the reports produced by the fashion industry as were made for the reports produced under the NFRD. According to the Fashion Revolution Fashion Transparency Index 2020 Edition, the majority of brands and retailers lack transparency on social and environmental issues, with fast fashion companies leading on transparency compared to the luxury brands. Good transparency performance in the fashion industry was also noted in the the Alliance for Corporate Transparency’s (2019) report for 2018. But transparency does not automatically lead to sustainability of the business practices in question:9 not only did the index show that more than half of the participating brands scored 20% or less on environmental and social issues, the highest scoring companies on transparency (e.g. H&M, C&A, ASOS) have business models based on overproduction and overconsumption. The low score on environmental and social issues transparency is all the more worrisome given the index itself is built on voluntary self-reporting (only half of the brands invited agreed to participate), potentially making the results positively biased (Steiner et al., 2018).

Aside from noting the need to address unsustainable practices in the fashion industry through the revision of the NFRD, the EU acknowledged the need to revise these practices in its EU Strategy for Sustainable Textiles, guiding EU fashion companies towards “a climate-neutral, circular economy where products are designed to be more durable, reusable, repairable, recyclable and energy-efficient” by making the COVID-19 recovery of the textile industry sustainable (European Commission, 2021). The sustainable textiles initiative is based on EU recognition that textiles is a priority sector for achieving a carbon-neutral, circular economy in a range of instruments: the European Green Deal, the Circular Economy Action Plan, the Industrial Strategy, and the Commission Staff Working Document “Identifying Europe’s recovery needs” accompanying the Communication “Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation”. The outlook of these policy documents, which is also expressed through concrete legislative proposals on sustainable corporate governance and human rights due diligence, favours a thorough transformation of unsustainable fashion practices, for which additional investment will be made available. To harvest these green investments, though, companies need to be aware of their sustainability hotspots and be transparent about them. This is essential to engaging in cooperative practices to find a timely solution in the industry as a whole. There must also be acknowledgment that fast fashion business models cannot survive in the long term: either due to the lack of resources (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017) or due to the lack of demand given the growing customer awareness around sustainability (McKinsey & Company, 2020) and the tendency for the market to require the internalisation of all negative externalities across their supply chains (UK Parliament, 2019).

4.2 Scope

The majority of EU companies in the fashion industry escape the application of the NFRD, as they can be classified as small and medium-sized enterprises that fall short of the Article 1(1) threshold. Nevertheless, the most impactful European fashion companies are obliged to report on the non-financial aspects of their business, e.g. LVMH, Inditex, Dior, Kering, Hermès, adidas, Luxottica, H&M, Zalando, Moncler, PUMA, Hugo Boss, Salvatore Ferragamo, YOOX Net-a-Porter Group, TOD’S, Brunello Cucinelli, GEOX, Van de Velde and Gerry Weber, among others. Beyond the division between fast fashion, luxury fashion and sustainable fashion, these companies have the broadest impact in terms not only of fashion consumption but also production due to their widespread supply chains. With greater understanding they therefore possess significant potential to minimise their negative impact while simultaneously positively impacting their whole value chain (Garcia-Torres et al., 2017). While sustainable fashion companies do not fall within the scope of the NFRD, a number voluntarily publish non-financial reports as part of their core business model and provide the core sustainability information the NFRD seeks from stakeholders in all industries (e.g. MUD Jeans, Living Crafts, allSisters, Patagonia). Tackling the sustainability hotspots discussed in Section 2, these companies walk their talk without an external legislative impetus to do so. The question is why the fast fashion and luxury fashion companies are not striving to do the same, especially given that legislative obligations around the environmental and social considerations of business are well underway in the EU. The most obvious answer is that the predominant business models of both fast fashion and luxury fashion are inherently unsustainable. While luxury fashion is built on exclusivity and prestige that involves the use of unethical resources (e.g. fur, silk and labour outsourcing to further enlarge corporate profits) and environmentally unsound practices to keep the prices of their products high (e.g. incinerating unsold stock), fast fashion thrives on externalising negative environmental and social impacts, which allows them to produce and sell large quantities of garments for a low price. The formulation of the NFRD as it stands today allows for a cherry-picking approach, enabling the companies to determine for themselves what is material to report, making the non-financial reporting void in terms of its content and its ability to support a meaningful change towards more sustainable business practices. The following section analyses reports by three European “sustainability winners” in the three different categories (fast fashion, luxury fashion and sustainable fashion) to illustrate the shortcomings of the NFRD discussed in Section 3.

4.2.1 Fast fashion sustainability winners: a paradoxical situation. The cases of H&M, ZARA and C&A

H&M has continually been identified as one of the world’s most transparent and environmentally and socially sustainable fashion brands, despite belonging to the fast fashion industry and its business model of overproduction of low-cost clothing. By way of example, it has been recognised ten times as one of the world’s most ethical companies by the Ethisphere Institute, been included in the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index for the seventh year in a row,10 ranking in the top 10% of global sustainability leaders, and ranked 27th in Corporate Knights’ annual ranking of the world’s most sustainable corporations. H&M was listed among the leading companies in Fashion Revolution’s 2020 Fashion Transparency Index and is a part of the FTSE4Good Index Series. It has been recognised as one of the world’s biggest users of recycled cotton, recycled wool, recycled nylon and lyocell. H&M is also included in the Carbon Disclosure Project’s 2019 Climate Change A List, which recognises the world’s most pioneering companies in environmental transparency and performance. H&M also ranked third in the Sustainable Cotton Ranking, which assesses how 77 companies score on their policy, traceability and actual uptake of sustainable cotton, and in Stand Earth’s Filthy Fashion Scorecard, assessing the climate commitments of 45 fashion brands. Moreover, the Stockholm School of Economics’ annual “Walking the Talk?” report on the sustainability communication of Sweden’s largest listed companies named the H&M Group as one of the best in terms of “walking the talk”. As regards its policy on wages, H&M was named the leading company in four categories (policy, integrating findings, tracking performance and transparency) in ASN Bank’s 2019 “Living Wage in the Garment Sector” review. At the Corporate Responsibility Reporting Awards, the H&M Group was the winner of the Creativity in Communication category and second place in the Openness & Honesty, Relevance & Materiality and Best Report categories. In terms of one-off efforts, H&M was awarded the PETA Vegan Homeware Award for Best Wool-Free Rug for its 100% recycled cotton patterned rug from its Conscious Collection. It may be claimed that H&M has been selectively transparent, highlighting individual sustainable action that very modestly mitigates negative impacts, but even if such transparency were more material, transparency does not automatically translate to sustainability. By way of example, to be truly transparent, H&M would have to report on its sustainability hotspots across its value chain and their mitigation, while in reality it provides information on their environmental and social policies and management in its annual non-financial report. To be truly sustainable, H&M would need to change its production processes, comprised of high production volumes, quick turnaround times and low prices, which would not allow 4.3 billion garments worldwide to be discarded – a significant contribution to the creation of “throwaway culture”. As NFRD only requires environmental matters to be disclosed “to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s development, performance, position and impact of its activity” (NFRD, Article 1.1), the corporation is free to focus on the positive developments in terms of ameliorating its positive impact (or better said, diminishing its negative impact) compared to its benchmark of “business as usual”, which is often not even their past performance but rather the performance of their peers “who are doing even worse” (Cline, 2013). Not linking the matters that must be reported on with scientific goals and international EU obligations in terms of climate action and sustainability challenges gives the paradoxical result of corporations reporting on their business model (in this case fast fashion)11 without needing to provide a clear plan for a holistic transformation of that model to tackle tonnes of their unsold clothes being incinerated each year (New York Times, 2018). This immaterial nature of H&M’s sustainability report actually complies with NFRD requirements, as it does give a brief description of the company’s policies on matters of environmental and social sustainability and due diligence processes – their impact and size is irrelevant, as long as such policies and processes exist and are active.

The most promising requirement in the directive is that on the disclosure of “principal risks related to those [sustainability] matters linked to the undertaking’s operations including, where relevant and proportionate, its business relationships, products or services which are likely to cause adverse impacts in those areas, and how the undertaking manages those risks” (NFRD, Article 1.1.d). This results in a mere acknowledgment of H&M’s negative sustainability impacts and very modest planned actions with no KPIs to quantify those plans, which are reported in a condensed version without truly allowing the actual transformation of H&M’s practices to be discerned on its core sustainability hotspots.12

The same considerations apply to Zara. Despite pledging to use 100% sustainable fabrics by 2025 (including recycled polyester and organic cotton), its sustainability strategy shows little promise, as the commitments are not supported by concrete actions, and the actions envisaged bring about unsustainable outcomes (e.g. mixing recycled polyester and organic cotton in the same sustainability strategy). Even disregarding the fact that a garment produced from organic cotton mixed with recycled polyester cannot be recycled, this particular sustainability strategy does not remedy the fact that the Inditex group of which Zara forms a part still produces 1.6 billion garments annually (Fashion Revolution, 2020). This volume not only requires enormous natural resources, but also results in a vast amount of waste due to overproduction.

Much like the H&M Group, Inditex is constantly receiving sustainability awards (e.g. most sustainable retailer according to the Dow Jones Sustainability Index; 5th in the FTSE4GOOD index; 4th place in the Spanish ranking Merco Responsabilidad y Gobierno Corporativo; and 205th place in Newsweek’s Top Green Companies in the World), and yet its non-financial reporting reveals serious shortcomings in terms of sustainability and underlying transparency. With a final score of 43%, according to the self-assessment-based Fashion Transparency Index 2020, its commitment to sustainable transformation is questionable, its non-financial report is of limited value and fails to provide the information required by the NFRD. While Zara scored remarkably high for the transparency of its policy and commitments (86%), it also scored remarkably low for the traceability of its operations (19%). This is alarming even in the absence of a more detailed analysis of Zara’s non-financial report and is supported by the relatively low score for “walking the talk” (40%).

The sustainability report is available only at the corporate group level, and shares many similarities with H&M’s. The assertion in the report that 63% of its global electricity consumption comes from clean sources highlights is not elaborated on in the report itself. Neither is the claim that 92.67% of their stores are eco-stores, beyond the information that A-rated energy efficiency air conditioning is to be installed across its stores. Claiming that sustainability is embedded in their products’ entire life cycle and that designers will be trained on the circular economy by the end of 2020, the report does not show the simultaneous fall in clothes production that would attest to circularity being a true business objective, accommodating the longer garment-life and designs that facilitate repair and reuse. Neither is the information on the use of more sustainable fibres informative per se: the fact that recycled material use has been increased by 250% and that of sustainable cotton by 105% gives limited information on the allegedly diminishing negative environmental impact of such changes and no information at all about the future recyclability of garments produced by these materials.

As far as social sustainability is concerned, the launch of a new strategy is mentioned, as well as accompanying audits. Yet the outcome of the initiative remains unclear, especially as regards the social sustainability hotspots (e.g. forced labour, child labour, fair wages, etc.). Similarly, when it comes to the environmental sustainability of the supply chain, the aim of reaching the Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals target in 2020 has not been met, with the report referring only to the commitment itself and to the creation of a list of existing chemicals (getting to know their own production processes, rather than implementing concrete actions to mitigate their negative environmental impact).

While Inditex prioritises the eco-efficiency of its head offices, logistics platforms, transport, distribution operations, websites and stores (with 92.67% of their owned stores complying with its Eco-Efficient Store Manual), this is unrelated to the core Inditex (and Zara) activities with the highest negative social and environmental impact. The report does not elucidate the actual mitigation of their total negative environmental and social impact through those actions, especially given the modest reduction in energy use of these accompanying activities. It is safe to say that Inditex’s reduction of scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions by 35% per m2 is due to their use of clean energy (63% of their overall energy consumption in the year 2019).

The picture is even less clear when discussing circularity. The creation of a used clothing collection scheme in 2,299 stores in 46 markets is noted, but there is no information on how those garments re-enter the production chain. The reported data of using 14,000 tonnes of their own recycled cardboard as online sale boxes is uninformative: how is the recycling carried out? How are the online sales optimised to ensure optimal packaging? Add to that the information that 91% of waste generated in headquarters, logistics centres and factories were handled by experts, circularity does not seem to be ensured and Inditex’s approach to circularity is very lacking in transparency. Last but not least, Inditex’s philanthropic actions of donating clothing and employee volunteering by no means diminish their environmental and social impact. The issue of overconsumption, clothes waste and the manufacturing procedure per se is barely addressed, which may be said to be a total failure of Inditex’s non-financial reporting.

C&A, like the H&M Group, has been considered a transparency winner, holding the second-highest score right after H&M in the Fashion Transparency Index. It scores 97% for disclosure on policies and commitments, 100% for disclosure on governance, 70% for traceability and 59% (the highest score awarded) for transparency on human rights and due diligence processes. Yet there is a stark difference between the sustainability approaches of H&M and Inditex on one side, and C&A on the other. In terms of circularity, beyond policy statements and commitments, C&A has implemented and developed many circular practices, and changed their business model per se. In 2018 C&A was the first European retailer to introduce Gold-level Cradle to Cradle Certified jeans; it developed the first Platinum-level Cradle to Cradle Certified denim fabric; and it verified in 2019 that 100% of its cellulosic fibre suppliers to Europe were low risk for the use of fibre from ancient or endangered forest products. While C&A is also guilty of providing limited information regarding its recycled items (if they can be recycled again) and the percentage they comprise of C&A production as a whole, and it is true that the data on the “We Take it Back” programme fails to explain where the garments end up, it has implemented a successful supply chain oversight programme, allowing it to know and mitigate its negative environmental and social impacts.

The company is taking a science-based approach to climate change adaptation, with concrete targets and actions to support its policies and commitments, thereby covering its environmental and social hotspots (as well scope 3 of CO2 emissions). C&A also openly discusses its human rights violations, due diligence and concrete steps and audits undertaken to ameliorate the situation. Furthermore, its subsidiary in Brazil has been the pioneer in this kind of sustainable innovation: C&A applied the same approach across its corporate group, leading by example outside of the EU.

Understanding that the transition from a fast fashion company to an environmentally and socially sound business model cannot be carried out in a short time-frame, C&A is an example of how a company can tackle its most relevant sustainability hotspots and “walk the talk”, especially when compared to H&M and Zara. While overproduction still needs to be tackled, as well as the content of their “We Take it Back” programme, its progress is documented, monitored and its actions closely follow C&A’s sustainability-related policies and commitments. But the transparent and clear C&A non-financial report is not the source of C&A’s organic change, more the other way around: C&A’s organic commitment to sustainable transformation allows them to provide a coherent, relevant and material non-financial report, quite different from the general practice in the fast fashion industry.

4.2.2. Luxury fashion sustainability winners: beyond greenwashing?

Luxury fashion, due to its exclusivity and the use of high-quality material, has been seen as a lesser threat to sustainability than fast fashion. Yet the luxury fashion companies have also been criticised for their negative environmental and social impact (albeit sometimes for different reasons), and (pre-NFRD) they have rarely voluntarily disclosed their environmental and social impact in their annual reports. To that effect, the non-financial reporting practices of Kering, Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton (LVMH) and Moncler will be analysed, allowing conclusions to be drawn on the nature of the influence of NFRD on luxury fashion, allowing for further suggestions for the revision of the NFRD.

Kering is a global luxury group, containing the brands Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, Brioni, Boucheron, Pomellato, Dodo, Qeelin, Ulysse Nardin, Girard-Perregaux and Kering Eyewear. It created its 2025 sustainability strategy in 2017, aiming to reduce its environmental footprint by 40% through three pillars: care (reducing environmental footprint and preserving natural resources with the use of innovative tools), collaborate and create (innovative alternatives using an open source approach). As a member of the UN Global Compact, it integrates the ten principles into its business: supporting and protecting internationally proclaimed human rights and not being complicit in their abuse; upholding the freedom of association and effectively recognising the right to collective bargaining; eliminating all forms of forced and compulsory labour; effective abolition of child labour; elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; a precautionary approach to environmental challenges; undertaking initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; promoting greater environmental responsibility; development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies; and working against corruption. Furthermore, Kering developed its own sustainability principles, building further on its commitments under the UN Global Compact, while also acknowledging the applicable international conventions. Ten main themes have been determined for the indicators used to monitor Kering’s environmental impacts through a web-based reporting tool: energy consumption, water consumption, waste production, paper consumption, packaging consumption, consumption of raw materials, transport (BtoB, BtoC and company cars), air pollution, environmental management, and general data on the site (surface area, turnover, etc.).

The existence of a methodological note to accompany Kering’s non-financial report supports relevant transparency around the sustainability of its actions as it allows for comparability with the reports of other companies beyond the reported data itself. It also allows for the amelioration of the company’s own methodology in assuring impact where the most action is needed to tackle corporate unsustainability. Kering is transparent about the scope of its reporting and the brands included, acknowledging the complexity of the task for large multinational conglomerates. Kering’s main contribution to non-financial reporting is without doubt its sustainability manifesto, which urges accountability in the industry to be measured by a new profit and loss account – an environmental one – rolled out across all of its brands by the year 2016. The environmental profit and loss account measures environmental impacts across the entire supply chain, providing monetary values for these impacts. It enables comparisons to be made (both intertemporal and across the industry), incorporating environmental sustainability hotspots at the core of the fashion industry reporting: carbon emissions, water use, water pollution, land use, air pollution and waste. By translating environmental and social concerns into monetary values, the comparison between business years is facilitated, allowing for meaningful interpretation of progress in the light of the accompanying financial report. By way of example, their 2019 group environmental profit and loss account was stable compared to 2018, which represents substantial progress given “the steep increase of income on a pro-forma basis, the EP&L intensity (€ EP&L per €1000 revenue) decreased by 14% between 2018 and 2019” (Kering Environmental Profit & Loss 2019 Group Results, p.1). Kering reports not only on the combined outcomes, but also lays out the distribution of impacts across the supply chain, acknowledging that its most significant impacts are generated in the supply chain, in particular from the production and processing of raw materials. Kering’s social sustainability actions are based on its “collaborate” approach, as reported in its Modern Slavery Statement for 2019. As with environmental sustainability, Kering ticks all the boxes on the social sustainability hotspots in the fashion industry through its due diligence approach – from fair wages to questions of diversity and general human rights questions.

LVMH is the leading global luxury products group, gathering 75 prestigious brands under its umbrella. Its analysis is indispensable to this chapter in the light of the fact that it operates (under the same strategy) in five large markets: wine and spirits; fashion and leather goods; perfume and cosmetics; selective retailing; and watches and jewellery. Its strong claim of “making sustainable development a strategic priority” calls for deeper scrutiny to be made of its practices and non-financial reports, especially as approximately half of its revenues derive from activities in the fashion industry. LVMH has made sustainable development a strategic priority since its founding. As early as 1992 it established an Environment Department, while Hennessy, one of its brands, launched the first analysis of a product’s lifecycle. In 1995, the Perfumes & Cosmetics Maisons created an ethno-botany department to protect species of plants used in cosmetics. In 1998, Hennessy was the first wine and spirits producer in the world to receive the ISO 14001 environmental certification and Cascade was deployed, a tool to assess the environmental footprint of the Maisons and prioritise action. In 2001 LVMH produced its first ever environmental report in the luxury goods industry, and in 2002 it began trialling its process of CO2 emissions management. Like Kering, LVMH joined the Global Compact in 2003. Since then, LVMH has been continuously developing and ameliorating its sustainability policy and tools (e.g. developing its own standards and practices) and has been celebrated as the industry leader in sustainability.

LVMH separates its non-financial reporting into an Environmental Responsibility Report and a Social Responsibility Report. Both are incredibly detailed and as developed as their financial reports. In terms of environmental sustainability, LVMH took a scientific approach and developed LVMH Initiatives For the Environment, helping innovative answers to be given to questions in areas such as the environmental emergency, reducing the environmental footprint, protecting biodiversity, and so on. Its environmental performance is based on nine core elements: eco-design; secure access to strategic raw materials; traceability and compliance of materials and products; supplier environmental and social responsibility; preservation of critical skills; impact of CO2 from operations; environmental excellence; product lifecycle and reparability; and ability to answer customers’ questions. This allows the most relevant scientifically defined environmental sustainability hotspots to be traced and measured. The report is centred around the achievement of four main objectives: a product objective (improving the environmental performance of all products); a sector objective (applying the highest standards in 70% of sourcing channels; 100% to be achieved in 2025); a CO2 objective (reducing emissions by 25% compared to the 2013 level, focusing primarily on stores); and a site objective (improving sites’ key environmental efficiency indicators – water consumption, energy consumption and waste production – by at least 10%). The detailed reporting on each of these aspects reveals that almost all of the targets have been achieved, allowing for further advances and ameliorations through new environmental goals. The report also outlays the certifications used to assure their supply chain is environmentally sustainable.

On biodiversity, more needs to be done, as they have not shied away from using the crocodile skin as a production input (or leather in general). Similarly, in terms of CO2 emissions, focusing solely on stores with a modest energy consumption decrease of 25% is some way short of science-based targets, which requires changes to the CO2 emissions in their supply chain. LVMH reduces CO2 emissions by upgrading industrial and administrative sites (by the end of 2019, 60% of the group’s sites were ISO 14001 certified) and reducing the scope 1, scope 2 and scope 3 carbon footprints of transportation and raw materials. LVMH’s approach is holistic: the focus on the environment has been one of its guiding principles for almost three decades, something that is also reflected in its non-financial reporting, remedying the shortcomings of the NFRD directive. Visualising their actions and contributions in a Sustainable Development Goals chart furthers the transparency and cross-industry comparability of their non-financial report.

The lesson to be learned from LVMH’s environmental sustainability reporting is the need for focused transparency, addressing not only the sustainability hotspots of the fashion industry but continuously innovating and refining the approach towards mitigating negative environmental impacts. This should be embedded in the revised NFRD.

The same applies to social sustainability reporting, which is based on four priorities: respecting the uniqueness of their employees; passing on and developing savoir-faire; supporting its employees by improving their safety and well-being; and empowering local communities. In terms of actions supporting diversity, LVMH works in several thematic fields: it promotes diversity and fosters inclusion at work; improves equality and promotes career development for women (75% of LVMH’s workforce); supports people with disabilities into work; and structures knowledge transmission around older employees to harvest existing knowledge. To facilitate the passing on and developing of savoir-faire, LVMH recruits talent to safeguard the future of tradition; contributes to the continuity of savoir-faire (preserving high quality while ensuring sustainable outcomes); and develops employee skills throughout their entire career. In terms of improving employees safety and wellbeing, LVMH protects the wellbeing of employees by placing their motivation and work-life balance at the heart of their excellence-oriented approach; by improving health and safety at work across their supply chain; and by encouraging dialogue across the corporate structure. In terms of empowering local communities, LVMH plays an active role in the communities in which it operates by injecting growth, innovation and employment; it creates employment opportunities and economic momentum; it aids the re-inclusion of the long-term unemployed and young people into work; and it supports vulnerable populations through philanthropy. As with their environmental reporting, their social sustainability reporting also includes a graphical representation in terms of the Sustainable Development Goals. But, in contrast to its environmental sustainability reporting, LVMH gives less attention to social sustainability hotspots in its report, suggesting that the supply chains are as socially sustainable as they claim to be, without direct intervention by LVMH to ameliorate the challenging situation in terms of the social sustainability of fashion in general.

Moncler, the last company analysed in this subsection, is originally a French company that is currently headquartered in Italy and produces high-level outerwear collections that are unique products of the highest quality – “timeless”, versatile and innovative. Moncler takes sustainability very seriously: it was named a textiles, apparel and luxury goods “industry leader” in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index the first time it was included in the ranking, showcasing how slow fashion based on natural materials can achieve industry standards while being socially and environmentally sustainable. For social sustainability (human rights, human capital development and health and safety) it scored 85 (against an industry average of 32) and 92 for environmental sustainability (product stewardship, operational eco-efficiency and environmental policy and management systems) against an industry average of 41.

Moncler’s consolidated non-financial statement reports on its responsible business management in terms of its governance model, risk management, sustainable value creation and sustainability plan, providing a holistic overview of the sustainable actions that provided the results included in the report. Its sustainability governance is carried out through a separate sustainability unit, which created Moncler’s own materiality matrix as an expression of its sustainability hotspots and defined Moncler’s stakeholders and their engagement in detail. The Born to Protect Sustainability Plan expresses commitment to an increasingly sustainable and responsible long-term development through five priority commitments: fighting climate change, integrating a circular economy model, promoting a responsible supply chain, fostering inclusive collaborations, and giving back for the social and economic development of local communities. On climate change, it has achieved 100% renewable energy in its facilities in Italy and is aiming for 100% renewable energy at the global level by 2023 and carbon neutrality for its operational sites by 2021. These goals are coupled with actions for achieving energy efficiency and transport emissions monitoring.

In terms of circular economy principles, Moncler has launched a Life Cycle Assessment project while simultaneously including the use of recycled materials in its production and eliminating dangerous substances from its production processes. To give it further substance, Moncler is launching Extra lift repair services globally as well as the Take Me Back global project to extend products’ life, while simultaneously mitigating the environmental impact of its packaging. When it comes to responsible sourcing, the progress reported is very modest and requires further attention. In the framework of the promotion of fair workplaces, the required supplier mapping is taking place, supporting further work on responsible sourcing. Despite being presented as a sustainability leader in the field of luxury fashion, Moncler’s non-financial report raises very similar concerns to the non-financial reports of fast fashion companies: not all the company’s sustainability hotspots are noted, and those issues that are disclosed show limited transparency.

While Moncler seems to be setting out on the sustainability path, defining its sustainability hotspots and trying to find where and how to start, Kering and LVMH have already made substantial progress on the matter, at least in terms of defining their sustainability hotspots, priorities for action and mapping their global supply chains as a pre-condition for meaningful action. While Kering, as a sustainability leader in the luxury fashion industry, approaches environmental and social sustainability in great detail, allowing for intertemporal and corporate comparability of the data, LVMH should replicate its approach to environmental sustainability in its social sustainability.

It might, intuitively, be expected that the inherent characteristics of the business models in luxury fashion allow it to embed sustainability in the existing structures without the need for deep restructuring and that this would decrease the need for greenwashing. But the analysis of the actions and reporting of three separate luxury fashion companies shows that this depends on the company and whether they have embedded sustainability as a core principle in their business model. Where they achieve this, the reporting and action follow suit and are relevant and comparable, where they do not, similar challenges arise as in fast fashion companies.

4.2.3. Sustainable (ethical) fashion: role models for the NFRD revision?

To meaningfully conclude the present section on non-financial reporting in the fashion industry, the present subsection analyses the functioning and the sustainability reporting of sustainable (ethical) fashion companies. Created and guided by sustainability as their core business rationale, they have an inherent need for heightened and focused transparency and timely communication about their sustainable actions to their stakeholders. The analysis of three European companies, namely Patagonia, Armed Angels and MUD Jeans, will conclude Section 4, and serve as a role model for the revision of the NFRD.

While Patagonia is not an EU-based company, it represents a textbook example of a forward-looking sustainable business model in fashion, and its reporting practices follow suit. Patagonia is a US-based clothing company founded in 1973 that markets and sells outdoor clothing – “in business to save our planet”. In 2012 Patagonia became a Certified B Corporation, a for-profit company that meets “rigorous standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency” (Certified B Corporation, 2019). Patagonia considers itself an “activist company”, always innovating on sustainable practices that can be embedded in its practices to minimise their negative environmental and societal impact (it innovates even in the field of family/maternity leave policies). Beyond its core business practices, Patagonia commits 1% of its total sales to environmental groups through 1% for the Planet, and in 2016 it passed on 100% of sales from Black Friday to environmental organisations. It also actively advocates for sustainable business practices through its political engagement, acting as a global industry leader.13 In 2018 the company even donated the $10 million it received from tax cuts to “groups committed to protecting air, land and water and finding solutions to the climate crisis” (Adweek, 2018). Patagonia boycotted Facebook and Instagram advertising after it entered a US civil rights boycott movement, using its corporate power for the greater good.

In terms of sustainable corporate practices, Patagonia has adopted six specific benefit purpose commitments: 1% for the Planet, Build the Best Product with No Unnecessary Harm, Conduct Operations Causing No Unnecessary Harm, Sharing Best Practices with Other Companies, Transparency, and Providing a Supporting Work Environment. Its corporate reporting follows suit and is divided into these six sections. The category “Build the Best Product with No Unnecessary Harm” reports on its apparel material sources, environmental certification(s), product care and repair guides, global repair centres and supplier policies. Aside from reporting on its highlights (becoming a climate-neutral company, raising the product quality bar, closing the loop with worn wear, collection made from recycled and solution-dyed materials, long root beer, regenerative organic certification pilots, paying a living wage throughout the supply chain), it also objectively reports on the remaining challenges (e.g. increasing its footprint even as it decreases the use of virgin materials and implements garment recycling). This distinguishes Patagonia from the sustainability reporting of the large fast fashion conglomerates.

In the category “Conduct Operations Causing No Unnecessary Harm” Patagonia describes its commitment to becoming carbon neutral by 2025; its practice of sourcing 100% renewable electricity for its owned and operated facilities in the US; its 100% use of recyclable retail store receipt paper; its global electricity use and scope 1 and 2 carbon emissions. While it has reported a growth in the use of electricity and scope 1 and 2 carbon emissions, it has also worked on making its global facilities run on 100% renewable energy, tackling the inherent trade-offs of achieving truly sustainable outcomes (as it also has in terms of going zero-waste).

In the section “Sharing Best Practices with Other Companies” Patagonia reaches beyond its own transition and progress and aims to aid other enterprises embedding best practices into their own operations. It reports on investments in other responsible businesses, the amount of fishing nets repurposed into Patagonia products and speaking engagements, among other activities. This part of the corporate report discusses the regenerative organic certification, the B Corp Climate Leadership Summit and notes the challenges with developing its own standards for adoption.

On transparency, Patagonia notes its longstanding tradition of disclosing its suppliers, having an active blog revealing new facts on unsustainable corporate practices and the annual Patagonia competition for students to propose solutions to lessen the environmental impact of single-use packaging for apparel and food products by 2025. It also reports on actively engaging in solving the issue of microfibres and their reduction, publishing guidelines for reducing microfibre shedding at home. Patagonia furthers its transparency practices by aligning its Tier 1 suppliers with the criteria of the Transparency Pledge Coalition, publishing a standardised list of factories with meaningful information.

In “Providing a Supportive Work Environment” it reports on the company’s advanced maternity and paternity leave policy, gender equality, and highlights its environmental internships and Earth University to create lifelong stewards of the planet, while noting the challenges of rising housing costs and a living wage. While the non-financial reporting by Patagonia is more aligned with BCorp than NFRD reporting, the comprehensive issues inherent in its sustainability report are highly informative about which information should be revealed by fashion companies to allow for the understanding of the actual impact of their business practices in environmental and social terms. The biggest lesson for the NFRD revision that can be taken from the Patagonia example is the transparency about the achievements and remaining challenges, together with the accompanying plans for amelioration.

The second company analysed, Armed Angels, is a German fashion label established in 2007 that designs a variety of garments made from sustainable textiles, selling them online and in-store in six countries. It seeks to compete with mainstream fashion, producing sustainable fashion that is simultaneously ethical and fashionable, and changing the perception that eco-friendly clothing is unfashionable. Being supply-chain aware, Armed Angels collaborate only with socially responsible companies that are fair-trade certified. Its corporate philosophy is built on three main pillars: being good to the environment, supporting fair trade and donating to charity. This is illustrated by the use of organic cotton in their clothing, avoiding large shipping distances to reduce CO2 emissions, paying more than minimum wage to its farmers in India and donating a euro of profits from every piece of clothing sold. These inherent characteristics of Armed Angels’ business model are also visible also in their non-financial reporting. The achievements are set out at the beginning of the report, the focus being on water, energy, CO2 savings and their circularity efforts, directly addressing the environmental sustainability hotspots of the fashion industry as a whole.

As regards social sustainability, the beginning of the report immediately addresses the company’s supply chain, setting out the actions carried out in the 2019 business year. In terms of sourcing practices, the company reports on its responsible sourcing and pricing, setting out the responsible on-boarding, true pricing, the goal of providing living wages and fair pricing, as well as addressing its production cycle, monitoring activities and subcontracting, outlining its best practices and challenges, providing a transparent and balanced account of the challenges facing the fashion industry and the company.

While the company is not a large conglomerate, this does not mean that the form and content of its reporting could not also be used also in a big company, especially given the fact that large corporate groups consist of many subsidiaries, which are able to produce such reports by themselves. It could be argued that obtaining all the necessary information requires major investment and substantial additional human resources, yet such knowledge and tackling corporate environmentally and socially unsustainable practices will shortly be required of EU companies by virtue of the upcoming revision of the EU corporate law framework.

The third fashion company whose best practices are relevant in terms of sustainable fashion and non-financial reporting is MUD Jeans, a sustainable and fair-trade certified denim brand from the Netherlands, founded on the principles of the circular economy. It aims at radically changing the fashion industry by taking the most popular fashion item in the world –jeans – and producing them in the most sustainable way without losing a timeless sense of style, allowing consumers to participate in the sustainable transition of the fashion industry.

Using discarded denim, their jeans are made from 40% recycled content, and the final products are leased to consumers. After a year, the consumers can switch the jeans for another pair and continue leasing, return them for recycling or upcycling purposes or keep them, with the lease entailing free unlimited repair services (the Lease A Jeans concept). MUD Jeans sells its products online and through a limited number of sustainable concept stores around the globe. The analysis of its non-financial reporting practices is important due to the companies’ circular business model, which further minimises the negative environmental and social impact of fashion through the business model itself.

The company reports substantial savings in terms of water consumption (300 million litres of water less in the last three years), CO2 production (avoiding 700,000 kilos of CO2 in the last three years) and waste (12,000 pairs of jeans saved from landfill and incineration in the last three years). Its reporting format follows its business model by providing information on targeted impacts, outlaying prima facie the positive environmental impact of the business practices in which it engages. MUD Jeans reports on innovation in terms of providing 100% recyclable garments, actively working on a social audit on the wage situation and going beyond climate neutrality, pioneering and ameliorating its sustainable business model and thereby indirectly revealing the remaining challenges regarding sustainability in the fashion industry. They are a small company that has experienced impressive growth and can share their experiences with the larger fashion players. Supporting circular consumption is their strength, but aside from focusing on circular consumption they simultaneously tackle their sustainability hotspots across their operations and are highly transparent about those practices too. Organic engagement is the lesson to be learnt from their corporate and non-financial reporting practices.

5. The strengths and the pitfalls of the NFRD: where could we do better?

As highlighted before, the aim of the NFRD is to “improve undertakings' disclosure of social and environmental information”, as this disclosure “is vital for managing change towards a sustainable global economy by combining long-term profitability with social justice and environmental protection” and “helps the measuring, monitoring and managing of undertakings' performance and their impact on society”. The directive is supposed to enhance the consistency and comparability of non-financial information disclosed across the EU, at a minimum achieving the provision of a “description of the policies, outcomes and risks related to those matters”, accounting also for supply and subcontracting chains to identify, prevent and mitigate existing and potential adverse impacts. The analysis carried out in this work aligns with the opinion of the Commission that these aims have yet to be achieved. Considering the existing reporting practices in the fashion industry, the aims of the EU Green Deal in terms of achieving net zero greenhouse gases in 2050 and decoupling the economic growth from resource use in general, and the EU strategy for sustainable textiles – particularly concerning microplastics and circular efforts – the suggestions for the NFRD revision from the lessons learned in the fashion industry should aim at an ambitious overhaul of the initial directive to ensure policy coherence on the sustainability of the fashion industry.

5.1 The strengths of the NFRD as applied in the fashion industry