The Brexit Scenarios: Towards a New UK-EU Relationship

Documents CIDOB (Nueva época): 7

Authors Scenario #1: Bremain

Stuart A. Brown, Research Associate, LSE, Senior Research Associate, University of East Anglia, and the Managing Editor of the LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog

Tena Prelec, ESRC-funded doctoral researcher at the School of Law, Politics and Sociology, University of Sussex, and Editor of the LSE’s EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog

Author Scenario #2: A soft Brexit

Swati Dhingra, Lecturer in Economics, LSE, CEP, CEPR, CESIfo

Author Scenario #3: A harsh Brexit

Tim Oliver, Dahrendorf Fellow, LSE IDEAS

This publication brings together the papers presented at the workshop “Scenarios of a new UK-EU relationship”, held at CIDOB on May 20th 2016 and co-organised with the London School of Economics’ European Politics and Policy blog (LSE EUROPP). The workshop analysed the scenarios of the British referendum on European Union (EU) membership that will take place on June 23rd 2016 and discussed, among other issues, the negotiations between the British government and the EU, the referendum campaign, the internal developments in the United Kingdom (UK) and the EU and the scenarios that might prevail after the referendum. This publication presents three scenarios based on whether the UK will stay in the EU (“Bremain”), whether it will leave the EU following some form of agreement (“soft Brexit”) or whether it leaves it abruptly (“harsh Brexit”). The authors cover the economic, political, social and geopolitical effects of each scenario, attempting to devise the new UK-EU relationship in case these scenarios materialise. They pay particular attention to the political dynamics in the EU following the Brexit referendum and the effects on the European project, as well as on the future of the UK.

Scenario #1: Bremain (no return to the status quo)

Stuart A. Brown / Tena Prelec

A great deal of ink has already been spilled on the question of what a Brexit would mean for the UK and the rest of Europe. But the issue of what would happen if the UK were to vote to stay in the European Union has received far less attention. In some respects, this is understandable. While a Brexit would entail a radical reshaping of the UK’s relationship with Europe, and potentially have far-reaching consequences for the nature of European politics in general, the implications of a “Bremain” appear less momentous at first glance. Yet there are several reasons why we should be interested in the consequences of a vote to remain in the EU on June 23rd.

First, although the opinion polls point to an exceptionally tight race, there is a general expectation that the UK continuing to be a member of the EU remains the most likely outcome.1 This is apparent from survey evidence (Stewart, 2016), where even many of those who favour exiting the EU find it more likely that the remain side will ultimately win on referendum day. While this may not play out in practice, if a remain victory is the most likely outcome there is clearly some merit in assessing what the result would mean for the UK moving forward.

Second, it is worth noting that neither of the main campaigns in the referendum accept the notion that the UK’s relationship with the EU will return to “business as usual” following the referendum. David Cameron has built his campaign around the merits of staying within a “reformed European Union” and has argued that the outcome of his renegotiation secures a “special status” for the UK within the EU. Meanwhile, campaigners on the leave side frequently assert that remaining within the EU should not be viewed as a mere continuation of the present relationship. In the words of the justice secretary, Michael Gove (2016), for instance, “if we vote to stay we are not settling for a secure status quo, we are voting to be hostages locked in the back of the car driven head long towards deeper EU integration”.

So if a vote to stay within the European Union cannot be seen as simply the maintenance of the status quo, what might we expect to change? All things considered, there are at least three areas in which it may be anticipated that the referendum will have a significant impact on the UK and the rest of the EU.

Changes in the UK’s relationship with Europe

The first area in which there may be substantial changes following the referendum is the nature of the UK’s status within the European Union. The agreement secured by David Cameron in February had four key elements, broadly grouped around the themes of the eurozone and economic governance, competitiveness, sovereignty, and free movement.

With regard to the eurozone and economic governance, the main provision is the creation of a mechanism through which the UK can delay draft laws being proposed by eurozone countries. The concern here is ultimately to protect the UK from a situation in which members of the eurozone, by holding a majority of votes in the Council, could potentially isolate those states that are not part of the single currency and thereby undermine the integrity of the single market. The fact that the UK will only have the power to delay rather than veto proposals is seen as insufficient by many of those campaigning for a leave vote. The agreement does, however, establish a set of principles that are legally binding and which could form the foundation for future challenges to EU legislation.

The deal reached on competitiveness is arguably the least consequential of the four elements of the renegotiation. The agreement reaffirms the EU’s commitment to completing the single market for services, the digital single market, and the single market for energy, while also calling for the completion of future trade agreements with non-EU countries. While these are important priorities for the UK, it is difficult to pinpoint how the renegotiation constitutes a specific change in the EU’s approach as there was already a clear commitment to pursuing these aims.

In the case of sovereignty, the renegotiation established two key changes. First, it makes clear that the UK is not committed to future political integration within the EU and clarifies that the concept of “ever closer union” does not “compel all Member States to aim for a common destination”. Second, it establishes a so-called “red card” procedure, under which national parliaments would be able to challenge EU proposals if 55% of parliamentary chambers registered opposition. Although the red card procedure offers an extra element of accountability in principle, previous research (Hagemann, Hanretty and Hix, 2016) has demonstrated that the system would likely be in play in only a very small number of cases. It is worth noting that the pre-existing “yellow card” system, established under the Treaty of Lisbon, which allows parliaments to request a review of an EU proposal, has been used successfully (Cooper, 2015), although it requires only a third of parliaments to agree (rather than 55%).

Finally, the renegotiation contained a number of changes to the rules on EU migrants’ access to benefits. These include an “emergency brake” that would allow the UK to restrict access to in-work benefits for new arrivals for a period of four years (with this system being in place initially for seven years), as well as alterations to other benefits, such as the rate at which child benefit is paid for children living in other EU countries. Additionally, the rules have been tightened on the “abuse” of free movement rules, such as cases where non-EU family members have been permitted to enter an EU country and thereby avoid immigration rules.

The renegotiation and Britain’s EU policy: Still an awkward partner?

The deal has been sharply criticised by those on the leave side for failing to sufficiently reform the UK’s terms of membership, but other actors have noted that the reforms contained within the agreement will nevertheless alter the UK’s status. Open Europe, for instance, state that while “the deal is not transformative”, it is not “trivial” and amounts to “the largest single shift in a member state’s position within the EU” (Booth, 2016).

In some respects, the agreement has relevance beyond the substance of its reforms. The principle of a state altering its membership terms, particularly with regard to drawing a permanent line in the sand limiting future integration, has potentially far-reaching consequences. David Cameron is also the first British prime minister to formally state that the UK will never adopt the euro as its currency, and even among pro-remain voices within Britain there is a general reluctance to support policies such as euro membership or greater integration in areas such as foreign policy. In this sense, the renegotiation can be viewed as merely the latest development in a progressive hardening of the UK’s tone at European level, over and above the specific details of the deal agreed.

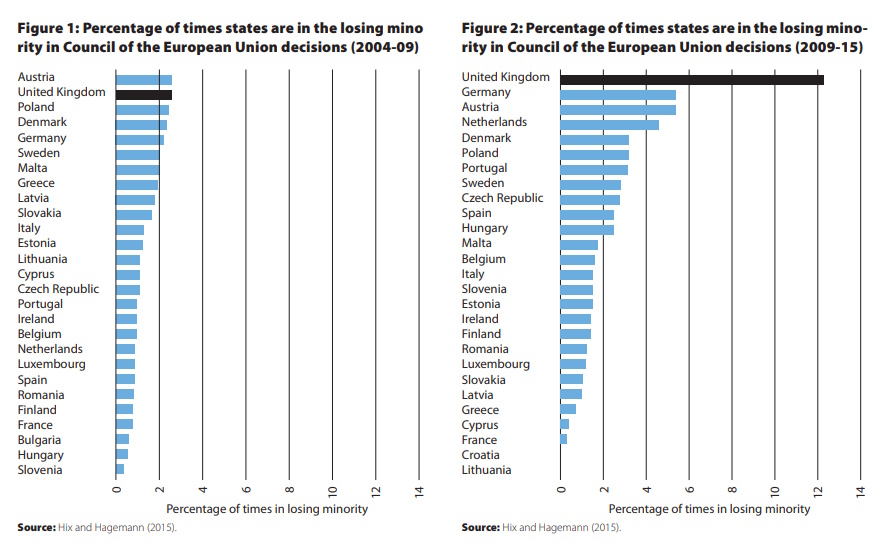

This trend can be traced at least as far back as 2010, when the Liberal Democrat-Conservative coalition first entered office. As Simon Hix and Sara Hagemann (2015) illustrate, the UK has shown far more willingness to lodge dissenting votes in the Council of the European Union since David Cameron came to power. Figure 1 below shows that while the UK was the second most likely state to formally cast a vote against a winning majority in the Council between 2004 and 2009, the percentage of times in which the UK has done so since 2009 has risen markedly to over 12% of votes, as shown in Figure 2.

Of course, the nature of European Council decision-making requires these figures to be placed in appropriate context. Council decisions are made in a climate of consensus, with many agreements not going to a formal vote. As such, the extent to which there has been a genuine shift in Britain’s EU policy since 2010 is debatable. It may be the case that the government simply wishes to signal its opposition to policies for the benefit of its domestic audience (Hagemann, Hobolt and Wratil, 2016). This is in keeping with previous displays of opposition by David Cameron, such as his decision to vote against Jean-Claude Juncker’s nomination as European Commission President in 2014 and his veto of the Fiscal Compact in 2011.

But in a broader sense, looking beyond the renegotiation, it might also be anticipated that after the referendum a more general shift could become evident in the UK’s approach to EU policy issues at European level. For instance, the UK has long been one of the strongest proponents (Ker-Lindsay, 2015) of enlargement, and has frequently expressed support for the accession of western Balkan states and Turkey to the European Union. However, the nature of the referendum campaign could mandate a shift away from this position. The prospect of Turkish citizens being granted the right to move to the UK has been raised as a particular concern (Mason and Asthana, 2016) by leave campaigners and it may become politically difficult for the UK to maintain its previous support for Turkish accession, if not its support for other states such as those in the western Balkans.

Ultimately, the nature of the referendum result could have an impact on the extent to which the UK will continue to be regarded as an “awkward partner” (Daddow and Oliver, 2016) within the EU. A sizeable vote for remaining in the EU could, in theory at least, provide the British government with more of a mandate to take a leading role in European decision-making. Alternatively, a narrow vote to remain would likely tie the government’s hands further and raise unprecedented levels of scrutiny as to the UK’s involvement in future integration.

Other factors will also play a role. If further integration within the eurozone leads to a gradual marginalisation of Britain from EU decision-making, despite the safeguards against this contained in the renegotiation, the UK would be left with a difficult choice of either accepting a reduced level of influence, or joining the euro and protecting its position as a central player in the EU policy process. The same effect may also arise with regard to the multitude of opt-outs the UK has agreed in recent years, including the opt-outs from Schengen and justice and home affairs cooperation. A decision to remain in the European Union, while ruling out any future integration, could leave the UK residing in an “outer circle” while the rest of the EU pursues closer cooperation in its absence. This is a particular issue given the ratification of any future EU treaty may well be politically toxic in the UK following a close result on June 23rd and would likely require another referendum due to recent legislation passed in the British parliament.

The nature of the referendum result and the response of the British government domestically in its aftermath will go some way toward settling these issues in the coming years. However, what is beyond doubt is that with the referendum substantially raising the salience of the EU issue among the British public, it is difficult to imagine that Britain’s EU policy, and its relative status within the EU’s institutions, will be unaffected, at least in the short term.

Changes within British domestic politics

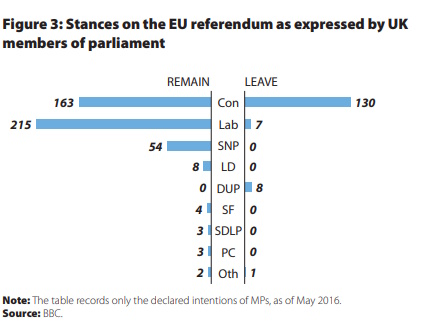

The UK’s referendum is of relevance not only for Britain’s relationship with the European Union, but also for domestic politics. The campaign is already having a profound effect on the discourses and policies of the main parties, most notably the Conservative Party, which is deeply split over the issue. Figure 3 below illustrates this picture, with Conservative MPs divided 163-130 in favour of a remain vote.

In contrast, the other main parties remain relatively united over the issue. A small number of Labour MPs have gone against the majority of their party in campaigning for a leave vote, but while Jeremy Corbyn has previously been highly critical of European integration, as leader of the party he has eventually articulated support for staying in the European Union. This has sent mixed messages to Labour voters, with opinion polls suggesting that around 50% of them were unclear on the party’s official position on the referendum just three weeks prior to the vote (Rowena, 2016). Nevertheless, the most important implications of the referendum will be for the Conservatives: even if Corbyn’s leadership comes under threat before the next general election, it is likely to be in relation to his wider electoral platform rather than the specific issue of the EU.

Conservative splits and the leadership contest

There are at least two major issues that the Conservatives would be obliged to face in the aftermath of a remain victory in the referendum. The first is how the party’s leadership should deal with the sizeable split that now exists among MPs. If the result is as close as expected, this could provide Cameron with a reason to attempt to heal the rift within the party by using a post-referendum reshuffle to integrate prominent Eurosceptics into the government. A perhaps less likely scenario, but one that is more plausible if the margin of remain victory is particularly large, would be for the prime minister to enter into open conflict with those on the leave side in the hope of removing rivals from positions of power and thereby shoring up his support base. The final approach may well be something of a “halfway” scenario, in which some figures who have been particularly robust in their campaigning become marginalised from the leadership, while others are integrated for the sake of maintaining party unity.

The second issue the party will have to face is the prospect of a leadership contest before the next general election, with David Cameron already having announced his intention to step down before 2020. Precisely when this contest will occur is a matter of open speculation. Some in the party, including Conservative MPs Andrew Bridgen and Nadine Dorries, have already called for Cameron’s resignation immediately after the referendum, even in the case of a remain vote (Sparrow, 2016). There is a general expectation that if the margin of remain victory is particularly large then the prime minister may be able to continue in office for some time; a narrow victory, by contrast, could make his position untenable and a new leadership contest could materialise fairly quickly.

And given the heated nature of the referendum, it is highly likely that this leadership contest will be dominated by the issue of Europe. Although some of the main candidates (Theresa May, George Osborne) have taken a pro-remain stance, there is a feeling among some of the party membership that the next leader should be a Eurosceptic (Michael Gove, Boris Johnson, Liam Fox, Priti Patel). The most recent survey (Goodman, 2016) by the Conservative website Conservative Home, for instance, indicates a strong preference for a Eurosceptic leader, with Michael Gove leading the list of candidates on 31%. While this is only a snapshot of the views of party members, it is clear that pro-remain candidates, such as George Osborne, who have previously been tipped as Cameron’s replacement, may find it substantially more difficult to win over the party in the aftermath of the referendum. Given that Gove is regarded as a relatively unpopular figure with floating voters, Boris Johnson remains arguably the most likely winner from a quick leadership contest.

However, regardless of the result on June 23rd, the Conservatives will be facing a period of political upheaval and it is difficult to determine how this will play out in the long term. The possibility of the party splitting, although still remote, cannot be excluded if the leadership fails to find a way to integrate the strong views that now exist on both sides of the European divide.

Would the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) emerge stronger from a remain vote?

Outside of the two main parties, one of the more interesting questions in terms of the effect a remain vote might have on the UK’s party system is the potential impact on UKIP. In the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, the relatively narrow win for the “No” side was followed by an almost immediate spike in support for the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP), who subsequently won a record 56 (out of 59) Scottish seats in the 2015 UK general election. Some of the factors underpinning this success were particular to the electoral situation within Scotland, but the notion that UKIP could experience a similar upturn in support following a remain vote in the EU referendum has nevertheless been the subject of some speculation among political commentators.

In practice, there are reasons to both support and reject this perspective. On the one hand, the referendum is creating a highly polarised atmosphere around the issue of Europe which UKIP, as the only major party with a united front in supporting a leave vote, would be well placed to capitalise on. This position would be made substantially stronger if the Conservative Party, following a victory in the referendum for David Cameron, declined to appoint an overtly Eurosceptic leader to take the party into the next general election.

But UKIP’s rise also has implications for Labour. The referendum could exacerbate Labour’s difficulties appealing to Eurosceptic working class voters, many of whom have switched to UKIP in recent elections. As stated by Matthew Goodwin (2016), the problem for Labour in this sense is that “while they almost unanimously push a pro-EU position, many of the voters who they have been losing since the late 1990s, and who the party needs if it is ever to return to power, think fundamentally differently about this issue”. This feeds into a wider sense of ambivalence toward the EU from those on the left of the political spectrum. Several prominent left-wing campaigners have voiced scepticism concerning the EU’s handling of the Greek debt and migration crises. And while this often stops short of advocating a Brexit, the support of figures like Yanis Varoufakis and his DiEM25 movement for “reforming the EU from within” speaks to those on the left with soft-Eurosceptic views.

There are, however, some important differences with regard to the Scottish example that may limit the potential for UKIP to experience a rise in support similar to the SNP’s. Even following a highly contentious referendum campaign, it is unlikely that the issue of Europe will retain the same degree of salience that independence held in Scotland following the 2014 referendum, where the entire party system has largely become polarised around the single issue of independence. Moreover, there is a degree of division on the leave side that was entirely absent in the case of Scotland. A split currently exists between two competing campaign organisations, Vote Leave and Leave.EU/Grassroots Out, which has persisted even after the former group was assigned the official designation as lead campaigner by the UK’s Electoral Commission.

Part of the SNP’s success was not only that it represented support for Scottish independence, but that it did so from a position of electoral strength, with a majority of members in the Scottish Parliament and a solid record in government. As such, UKIP may require a broader electoral platform than is presently the case if it is to secure wider mainstream appeal following the referendum. But a close remain result would undoubtedly present a clear opportunity for UKIP to capitalise on popular feeling among those on the leave side.

The generation gap and a second referendum

A final aspect that is worth considering in relation to the effect of a remain vote on British domestic politics is the question of whether the referendum would genuinely settle the issue long term. A substantial increase in support for UKIP could, as occurred in Scotland, raise the prospect of a second referendum (although this would actually be the third referendum held by the UK on Europe, with the first in 1975). Indeed, Nigel Farage has been open to this possibility, noting that a narrow remain win could make it extremely difficult to avoid holding a further referendum on the topic.

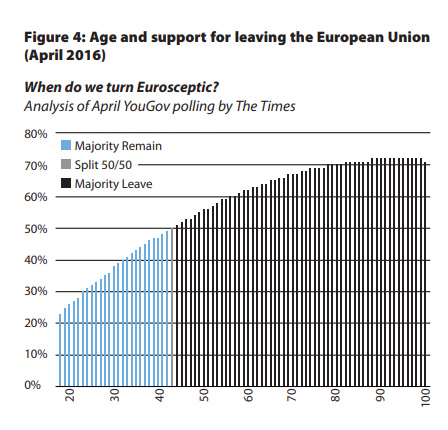

One aspect of relevance in this sense is the clear divide in views that exists within the UK between younger and older citizens. Polling by YouGov, illustrated in Figure 4 below, demonstrates a clear correlation between the age of citizens and their opposition to the European Union, with older citizens far more likely to favour a vote to leave in the referendum.

Research carried out by James Sloam (2016) suggests that the main factor underlying the distinctive stance taken by young voters is their prioritisation of key policy areas: young citizens are mostly concerned with “jobs, investment and the economy” and display a much higher interest in the EU’s role in protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms than older voters. Only one in five voters in the 18-24 age bracket cites “Britain’s right to act independently” as an issue of concern, compared to a third of all adults and almost half of those over 65.

This analysis indicates a mixed picture. Some of these priorities are likely to change with time: as citizens become older and acquire more stability in the labour market, the “creation of new jobs” may become less of a concern. On the other hand, there is also a suggestion that the younger generation has had a more international upbringing, with more opportunities to connect with their peers and to travel across the continent (e.g. through the Erasmus programme). This is likely to have created stronger bonds with continental Europeans than occurred with British citizens in the past. As such, it may be the case that support for the European Union will increase over time, reducing the demand for another referendum. Again, however, much will depend in this context on the nature of developments at European level in the coming years and how they impact on British public opinion.

Changes for the rest of Europe (and the world)

While the UK’s referendum will have clear consequences in terms of the country’s relationship with Europe, it will also potentially have a lasting impact on the nature of the European Union itself. One such effect could be the precedent set by the UK’s renegotiation. If the remain camp proves successful, then the renegotiation process pursued by David Cameron will also have been ratified by the British electorate. Theoretically, this might encourage other states to pursue similar renegotiations with a view to improving their own terms of membership.

However, the prospect of a form of “multi-level Europe” developing is potentially only the tip of the iceberg, as the UK is far from the only country to have experienced a rise in Euroscepticism since the financial crisis. Indeed, the UK’s referendum has been welcomed by Eurosceptic parties across the continent, and even the prospect of other referendums remains possible (Lorimer, 2016). Among the most outspoken backers of Brexit are Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France, who have already published a plan (Front National, 2016) for their own renegotiation and referendum, while criticising the deal achieved by David Cameron. Meanwhile in the Netherlands, Geert Wilders of the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) has referred to the referendum as “an enormous incentive” for other countries, and similar reactions have been articulated by the leader of the Italian Northern League (Lega Nord), Matteo Salvini. In Austria, the concept of an “Öxit” may well be reignited by the strong performance of the Freedom Party of Austria’s (FPÖ) presidential candidate, who obtained the largest share of the vote in the first round of presidential elections in April, although he narrowly failed to be elected in the second round.

What remains unclear is the effect a remain vote might have on these developments. Certainly, a British vote to leave the European Union might be expected to provide a substantial electoral boost to other Eurosceptic parties across Europe, but it is difficult to imagine that a decision to remain will take the heat out of the issue in other countries. The experience of Catalonia following the Scottish independence vote, for instance, suggests that a failed referendum can still act as a source of inspiration in other countries, with the debate becoming focused on the “right to decide” in their own electoral contest.

Finally, there are potential implications of a remain vote for the rest of the world. Several global institutions, such as the IMF (2016), have voiced concern at the economic consequences of a Brexit, while the president of the United States has been outspoken in his view that the UK should stay within the European Union (Stewart and Khomami, 2016). On the other hand, there has also been speculation that the Russian government would have a stake in a Brexit if it undermined the strength of the EU, although no official statement has been made to this effect. What is clear is that although states outside the EU are unlikely to be directly affected by a vote for the UK to remain in the EU, there may be some wider consequences with regard to global stability and EU relations with the rest of the world.

Bremain: Simply more of the same?

Ultimately, the precise developments that would follow a remain vote in the referendum would depend on a number of factors: the margin of victory, the effect on the leadership of the Conservative Party, the response from other parties in the UK, and the wider developments taking place in the rest of the EU. The one thing that does seem certain is that although the scale of the uncertainty that would accompany a remain vote is arguably of a lower magnitude than that associated with a Brexit, the referendum will set the agenda for not only the UK’s relationship with Europe, but also domestic British politics in the coming years. As such, there is no genuine “status quo” option on the ballot paper on June 23rd.

References

BBC. “Nigel Farage: Narrow Remain win may lead to second referendum” (17 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36306681.

Booth, Stephen.“What did the UK achieve in its EU renegotiation?” Open Europe (21 February 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://openeurope.org.uk/today/blog/what-did-the-uk-achieve-in-its-eu-renegotiation/.

Cooper, Ian. “The story of the first ‘yellow card’ shows that national parliaments can act together to influence EU policy”, EUROPP – European Politics and Policy (23 April 2015) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/04/23/the-story-of-the-first-yellow-card-shows-that-national-parliaments-can-act-together-to-influence-eu-policy/.

Daddow, Oliver and Oliver, Tim. “A not so awkward partner: the UK has been a champion of many causes in the EU”, LSE BrexitVote (15 April 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexitvote/2016/04/15/a-not-so-awkward-partner-the-uk-has-been-a-champion-of-many-causes-in-the-eu/.

Front National. “Redonner sa liberté à la France en 6 mois par référendum ? Le mode d'emploi patriote” (23 February 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.frontnational.com/2016/02/redonner-sa-liberte-a-la-france-en-6-mois-par-referendum-le-mode-demploi-patriote/.

Goodman, Paul. “Gove tops our next party leader survey for the second month running”, Conservative Home (3 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.conservativehome.com/thetorydiary/2016/05/gove-tops-our-next-party-leader-survey-for-the-second-month-running.html.

Goodwin, Matthew. “Think Labour looks out of touch now? Wait until the EU referendum campaign starts...”, The Telegraph (6 January 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/labour/12084459/Think-Labour-looks-out-of-touch-now-Wait-until-the-EU-referendum-starts....html.

Gove, Michael. “Michael Gove's full Brexit speech on Today programme”, Politics Home (19 April 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] https://www.politicshome.com/news/uk/foreign-affairs/news/73978/michael-goves-full-brexit-speech-today-programme.

Hagemann, Sara; Hanretty, Chris and Hix, Simon. “Red card, red herring: Introducing Cameron’s EU ‘red card procedure’ will have limited impact”, EUROPP – European Politics and Policy (13 February 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/02/13/red-card-red-herring-introducing-camerons-eu-red-card-procedure-will-have-limited-impact/.

Hagemann, Sara; Hobolt, Sara Binzerand and Wratil, Christopher. “Government Responsiveness in the European Union: Evidence from Council Voting”, Comparative Political Studies, 2016.

Hix, Simon and Hagemann, Sara. “Does the UK win or lose in the Council of Ministers?” EUROPP – European Politics and Policy (2 November 2015) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/11/02/does-the-uk-win-or-lose-in-the-council-of-ministers/.

IMF. “United Kingdom—2016 Article IV Consultation Concluding Statement of the Mission” (13 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.imf.org/external/np/ms/2016/051316.htm.

Ker-Lindsay, James. “The United Kingdom”, in: Balfour, Rosa and Stratulat, Corina, (eds.) EU Member States and Enlargement Towards the Balkans. EPC issue paper (79). Brussels: European Policy Centre, 2015, pp. 53-62.

Lorimer, Marta. “Europe’s far right parties have also been toying with the idea of quitting the EU”, LSE BrexitVote (3 March 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/brexitvote/2016/03/03/europes-far-right-parties-have-also-been-toying-with-the-idea-of-quitting-the-eu/.

Mason, Rowena and Asthana, Anushka. “Iain Duncan Smith says Turkey is ‘on EU ballot paper’”, The Guardian (10 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/10/iain-duncan-smith-says-turkey-is-on-eu-ballot-paper.

Mason, Rowena. “Labour voters in the dark about party’s stance on Brexit”, The Guardian (30 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/30/labour-voters-in-the-dark-about-partys-stance-on-brexit-research-says.

Sloam, James. “The generation gap: How young voters view the UK’s referendum”, EUROPP – European Politics and Policy (7 April 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/04/07/the-generation-gap-how-young-voters-view-the-uks-referendum/.

Sparrow, Andrew. “Conservative party turmoil escalates with open call for Cameron to quit”, The Guardian (30 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/29/andrew-brigden-conservatives-david-cameron-fractured-eu-debate-election.

Stewart, Heather and Khomami, Nadia. “Barack Obama issues Brexit trade warning”, The Guardian (25 April 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/apr/24/leave-campaign-obama-trade-warning-eu-referendum.

Stewart, Heather. “Nearly two-thirds of voters think UK will remain in EU, Ashcroft poll finds”, The Guardian (26 May 2016) (online) [date accessed: 31.5.2016] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/26/two-thirds-voters-think-uk-will-remain-in-eu-ashcroft-poll.

Notes:

1- What UK Thinks (2016), “EU Referendum: Poll of Polls”, last updated May 23rd 2016:http://whatukthinks.org/eu/opinion-polls/poll-of-polls/.

Scenario #2: A soft Brexit

Swati Dhingra

Introduction

Britain faces a choice. Remain part of the European Union and recommit to the European integration project, or leave and seek a new role in the global economy. This choice will have far-reaching consequences not only for how Britain is governed, but also for Britain’s economy and the well-being of British citizens. Who will be Britain’s trade partners in the twenty-first century? Where will British firms do business? Who will be able to come and work or invest in Britain? Would leaving the EU make us better off or worse off? Despite several studies, there is little public understanding of the economic consequences of leaving the EU. The debate has been dominated by studies undertaken by partisan groups affiliated with either the pro-EU or anti-EU lobbies. These studies have produced a wide range of estimates of the potential gains and losses from Brexit and have clouded, not clarified, public understanding of the economic consequences of leaving the EU. This paper draws on the latest academic research on the costs and benefits of international integration to provide a concise evidence-based assessment of the likely effects of Brexit on the British economy.

The EU is Britain’s largest trading partner, and the economic consequences of leaving the EU or renegotiating Britain-EU policies will have wide and complex effects on the British economy. Trade, foreign direct investment, migration and economic regulations would all be affected if Britain exits the EU. But we know little of what form Britain’s relationship with the EU would take following an exit or any renegotiation (so-called Brexit). This makes it difficult to predict how Brexit would affect the British economy. As a result, there is a wide range of estimates for the impact on the British economy, but many of the estimates reflect the prior convictions of those conducting the analyses. For instance, a UKIP study estimates a net loss of 5% of British GDP per year from EU membership and a study by the European Commission estimates a net gain of about 2% of British GDP per year (Thompson and Harari, 2013).

While we cannot predict the future with certainty, we can make useful economic forecasts by accounting for the uncertainty over different policies and by recognising the limits to our knowledge of economic behaviour. To accomplish this, we can focus on the impact of the most likely policies and provide a range of estimates to incorporate the uncertainty attached to different policy scenarios and economic estimates. By paying careful attention to how the forecasts have been produced, we can therefore use impact estimates to make informed policy decisions. I draw attention to high-quality forecasts of the impact of different policies that are expected from Britain’s future relationship with the EU. Applying economic principles for sound forecasting, I discuss the potential economic impact of Brexit with the aim of guiding future policymaking for Britain’s engagement with the EU and the rest of the world.

Economic estimates of future policy events always have some degree of uncertainty. But this uncertainty can be reduced by choosing policy assumptions and economic models that have empirical validity and are capable of generating robust forecasts. The main premise of this paper is that there will not be any substantial “trust deficit” and we can use standard analysis that has predicted the economic consequences of membership to back up what would happen if an exit is simply a reversal of EU membership. Using state-of-the-art economic studies, I discuss the best available forecasts of the effects of this “soft Brexit” on trade and investment in Britain.

International trade

In the same speech in which Prime Minster David Cameron raised concerns about Britain’s relationship with the EU, he emphasised that: “At the core of the European Union must be, as it is now, the single market. Britain is at the heart of that single market, and must remain so” (January 23rd 2013). The most direct channel through which the single market programme affects the British economy is bilateral trade with the EU. Being part of the EU ensures lower trade barriers between Britain and the EU, which expands bilateral trade. The share of Britain’s bilateral trade with the EU increased from 30% on the eve of joining the European Economic Community in 1973 to over 50% in the 2000s. In this section, I look at the overall impact of Brexit on the British economy through the channel of international trade.

According to economic theory, reductions in barriers to trade increase the economic welfare of consumers, businesses and workers. Consumers benefit from reductions in trade costs that reduce the price of imported goods and services. Import competition disciplines domestic sellers, who also reduce the prices they charge to consumers. While domestic sellers lose business due to competition from imports, they get access to new export opportunities that increase their sales and profits. This benefits workers who experience an increase in incomes from expansion of the more productive exporting sector. Workers in import-competing industries lose and need to be compensated. But the main economic insight from trade theories is that all these channels raise efficiency and therefore national income. The rise in total incomes is large enough to compensate the losses to workers and businesses in import-competing industries. Of course, compensating those who lose from international trade is not an easy task. But here we focus on the aggregate economic impact through the channel of international trade under different scenarios of Britain’s future relationship with the EU.

How would Brexit affect Britain’s trade with its biggest partner, and what impact would this have on Britain’s national income? To answer this, we first need to determine the impact of Brexit on future trade barriers with the EU, and then determine how these trade barriers would change trade volumes and incomes. These are the steps followed by most studies when they forecast the impact of Brexit on the British economy. The reason they reach different conclusions is because they differ in their assumptions on how much trade costs would rise following Brexit, and how to model the economy to translate the changes in trade costs into changes in trade volumes and incomes.

The first difference across the Brexit studies arises from the political uncertainty attached to the nature of Britain’s future trade ties with the EU. There is no clear policy on whether Britain will get the same trade concessions that it has currently, perhaps by joining the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), or whether it will face a period of higher trade barriers if it exits the European Union and does not immediately receive these concessions. The second difference arises because we have imperfect knowledge of what is the appropriate model of the economy, and the model estimates we have are measured with some margin of error.

I focus on the most reasonable trade cost increases and modelling assumptions, rather than summarising every study that has predicted the economic impact of Brexit. I start with a discussion of how Brexit might affect the costs of trading with the EU. Then I look at two different types of estimates. The first set of estimates come from a structural economic model which builds on standard economic assumptions used in the literature on quantifying the economic impact of trade. The second set of estimates are more data-driven in that they impose less structure on the channels through which international trade affects incomes.

Around half of Britain’s trade is with the EU, making up about 13% of national income. EU membership reduces trade costs between Britain and the EU. This makes goods and services cheaper for British consumers and allows British businesses to export more. Leaving the EU would lower trade between Britain and the EU because of higher tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. In addition, Britain would benefit less from future market integration within the EU. The main benefit of leaving the EU would be a lower net contribution to the EU budget.

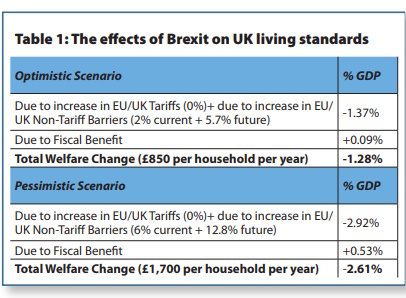

How does all this add up, and what would be the net consequences of Brexit on living standards in Britain? Dhingra et al. (2016a) develop a structural economic model of trade in 35 sectors in the 40 major countries of the world. Using this economic model, they quantify the effects of Brexit on trade and incomes under different Brexit scenarios. An optimistic scenario is that Britain swiftly strikes a deal that gets it deep access to the EU single market, as Norway currently has. In this Norway-style scenario, Brexit would be equivalent to a 1.3% fall in average British incomes (or £850 per household), net of the fiscal savings from lower membership contributions. The loss in income arises because Britain-EU trade faces some non-tariff barriers, like rules of origin checks and threats of anti-dumping duties, which apply to Norway too. Britain would also miss out on shaping and participating in future reductions in non-tariff barriers that are expected in important sectors for the UK economy like the services trade.

A pessimistic scenario for Brexit is that Britain is unwilling to accept the free movement of labour and the associated regulations that are part of the access price to the single market and faces the usual EU external tariffs that are imposed on non-EU members. Trade falls by more in this case because the EU imposes tariffs on British exports and non-tariff barriers rise further due to regulatory divergence. In this pessimistic scenario, Brexit reduces British incomes by 2.5% (or £1,700 per household).

Table 1 summarises the results and shows that the precise costs of leaving the EU depend on what policies Britain adopts following Brexit. Leaving the EU would increase non-tariff barriers to trade (arising from different regulations, border controls, etc.) and reduce Britain’s ability to participate in future steps towards deeper integration in the EU. The costs of reduced trade would far outweigh the fiscal savings. Britain transfers some resources to the EU, mainly to subsidise agriculture and poorer member states. Ignoring transition costs and any direct or indirect benefit to Britain from these fiscal transfers, leaving the EU would bring home the equivalent of about 0.53% of national income, according to the HMT. Netting out these fiscal savings from Brexit, there would still be a loss of £50 billion in the pessimistic scenario and a substantial £18 billion in the optimistic scenario.

The main advantage of using a quantitative economic model is that it provides numbers for how much real income changes under different trade policies, and this can be done with readily available data on trade values and trade barriers. A limitation is that it puts in economic structure that constrains the outcomes, so we evaluate the results using empirical studies that impose little theoretical structure on the effects of EU membership.

In a data-driven approach, we first need to pin down how much membership contributes towards trade volumes, once we have accounted for other reasons that could be driving both membership and trade. Baier et al. (2008) have studied the determinants of bilateral trade between EU member states using a method that fits data on trade flows well. They estimate the determinants of bilateral trade between two countries by using data on trade flows that are regressed on a number of determinants such as their economic size, the geographical distance between them, the cultural distance between them and other determinants. Having controlled for all these determinants of bilateral trade, they input indicators for EU membership of trade partners to isolate the effect of membership on trade volumes. They find that EU member states trade 40% more with other EU countries than they do with members of the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA). Half of Britain’s trade is with the EU, so using this estimate, leaving the EU to join the EFTA would reduce Britain-EU trade by 25% and Britain’s total trade by 12.6%.

The next step is to determine the rate at which a reduction in trade volumes would change incomes. As high income countries also trade more, we need to rule out the possibility that the causality runs from income to trade. This is done by focusing on changes in trade that are driven by changes in transport costs that do not independently affect incomes. The most credible estimates using this logic come from Feyrer (2009), who estimates that a 1% decline in trade reduces income by between 0.5% and 0.75%. The estimates capture both the direct effect of higher trade on income and also other indirect effects of increased proximity between countries, such as higher investments or knowledge diffusion. So these estimates should be interpreted as including some of the non-trade channels through which Brexit would affect British income, in addition to the direct effect of changes in trade volumes.

Combining this trade-to-income estimate with the estimated reduction in trade from Brexit, Dhingra et al. (2016a) estimate that leaving the EU and joining the EFTA would reduce British income by 6.3% to 9.5%. To put these numbers in perspective, during the 2008-09 global financial crisis Britain’s GDP fell by around 7%. Therefore, lower trade due to reduced integration with EU countries would cost the British economy far more than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget. These numbers echo the findings of several other studies such as the HMT, IMF and PwC reports.1

But our findings differ from the positive effects on British GDP estimated by Economists for Brexit (Minfor et al., 2015). Just like the latter, our analysis works with a general equilibrium model that takes into account interactions across markets. But, unlike them, we do not attribute all differences in prices across countries to regulatory costs. For example, if a cotton shirt bought by US consumers is cheaper than a cotton shirt bought by Italian consumers, Minford et al. (2015) would attribute the difference in price to onerous EU regulations. If Italian cotton shirts are more likely to be higher quality in terms of fabric or design, the higher price paid by Italian consumers reflects taste or quality differences. Our analysis nets out these systematic differences in products across countries to focus on prices that have been adjusted for quality. We then find that Brexit under any scenario would reduce trade and lower living standards in Britain.

International investment

Our data-driven estimates for the net costs of Brexit are much higher than the costs obtained from the structural model. One reason is that our estimates also account for the impact of other channels, such as Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Britain’s ability to easily access EU markets adds to the size of the market available to UK-based investors, making Britain a more attractive destination for FDI. So if Britain votes to leave the EU, what would happen to FDI flows coming into Britain and what can we say about the ultimate effects on British incomes of changes in FDI? This question has been left unanswered by most Brexit analyses because of obvious difficulties in putting a number on how EU membership matters for investments in Britain, and how much that affects British incomes. I draw on the investment analysis of Dhingra et al. (2016b) to provide estimates for the economic consequences of Brexit on UK living standards through the channel of FDI.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) comprises investments from outside a country to start up new subsidiaries, to expand existing establishments or to acquire local companies. The UK is a major recipient of FDI with an estimated stock value of over £1 trillion, about half of which is from other members of the European Union (EU), according to UK Trade and Investment. Only the United States and China receive more FDI than Britain.

Countries generally welcome FDI as it tends to raise productivity, which increases output and wages. FDI brings direct benefits as foreign firms are typically more productive and pay higher wages than domestic firms. But FDI also brings indirect benefits as the new technological and managerial know-how in foreign firms can be adopted by domestic firms, often through multinationals’ supply chains (Harrison et al., 2009). FDI can also increase competitive pressure, which forces managers to improve their performance.

One of the four basic freedoms of the EU is free movement of capital (alongside free movement of goods, services and people). Free movement of capital enables firms to invest in other European companies and to raise money in EU member countries. If Britain exits the EU, it can continue to have a bilateral tax treaty with the EU the way Norway has. But other factors might still reduce its ability to attract as much investment from inside and outside the EU. These would include higher transaction costs, such as different regulations and reduced access to EU markets. Being fully part of the single market makes Britain an attractive export platform for multinationals as they do not bear potentially large costs from tariff and non-tariff barriers when exporting to the rest of the EU. Multinationals have complex supply chains and many coordination costs between their headquarters and local branches. These would become more difficult to manage if Britain left the EU. For example, component parts would be subject to different regulations and costs, and intra-firm staff transfers would become more difficult with tougher migration controls. Finally, uncertainty over the shape of future trade arrangements between Britain and the EU would also tend to dampen FDI.

Supporters of Brexit claim Britain could attract more FDI outside the EU as it would be able to strike even better deals over trade and investment. But what does the data say? To determine the impact of EU membership on FDI, Bruno et al. (2016) use a gravity model to estimate bilateral FDI flows between 34 OECD countries from 1985 to 2013. They factor in various reasons that determine why foreign investors choose to invest in Britain, as opposed to Germany or France or Poland. Bilateral FDI flows in their gravity model depend on the GDP of the two investment partners, their GDP per capita, the bilateral distance between them and other factors such as the share of manufacturing output, and the share of exports and imports in the receiving country. The purpose of the exercise is to estimate how much more FDI would flow between two countries if the sender or the recipient joins the EU, once market size, distance and other determinants of FDI are controlled for. They find that EU membership increases inward FDI flows by 14% to 38%, depending on the exact statistical method. On average, then, Brexit is likely to reduce FDI inflows to Britain by about 22%. Being a member of the EFTA like Switzerland does not result in the FDI benefits of being in the EU. In fact, there isn’t much difference between being in the EFTA compared with being completely outside the EU, like the United States or Japan. So striking a comprehensive free trade deal after Brexit is not a good substitute for full EU membership.

How would reduced FDI affect incomes? There is much evidence that FDI brings benefits in terms of enhanced productivity. For example, Bloom et al. (2012) find that multinationals boost productivity in British establishments through enhanced technologies and management practices. But to get at the nationwide impact of FDI on output, we need to factor in the many complex ways in which FDI affects people and firms in multiple parts of the economy. This is a tricky task, but we can draw on the work of Alfaro et al. (2004), who estimate the effect of changes in FDI on growth rates across 73 countries. They find that increases in FDI have a substantial positive impact on GDP growth, especially for countries like Britain that have a highly developed financial sector.

To be very conservative, we assume a scenario where the Brexit-induced fall in FDI lasts only for 10 years and then reverts to its current level. Combining the estimated drop in FDI inflows from Brexit with the decline in growth projected by Alfaro et al. implies a fall in real income of about 3.4% after Brexit. This is equivalent to a loss of GDP of around £2,200 per household. Therefore, Brexit would have a sizeable impact on British incomes through reduced investments from abroad.

Conclusion

The economic consequences for Britain of leaving the EU are complex. But reduced integration with EU countries is likely to cost the British economy far more through greater trade barriers than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget. Leaving the EU would reduce trade between Britain and the EU because of higher tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. In addition, Britain would benefit less from future market integration within the EU. Just from the channel of reduced trade, the effects of Brexit would be equivalent to a fall in British income of between 1.3% and 2.6%. And once we include back of the envelope calculations for the long-run effects of Brexit on productivity, the decline in income increases to between 6.3% and 9.5%. Some of these losses can be reduced by future trade and investment arrangements with the EU after a soft Brexit. But the possible political or economic benefits of Brexit, such as better regulation, would have to be very large to fully outweigh such losses.

References

Alfaro, Laura; Chanda, Areendam; Kalemli-Ozcan, Sebnem and Sayek, Selin. “FDI and economic growth: the role of local financial markets”, Journal of International Economics, vol. 64, no. 1 (2004), pp. 89-112.

Baier, Scott L.; Bergstrand, Jeffrey H.; Egger, Peter and McLaughlin, Patrick A. “Do economic integration agreements actually work? Issues in understanding the causes and consequences of the growth of region...”, The World Economy, vol. 31, no. 4 (2008), pp. 461-497.

Bloom, Nicholas; Sadun, Raffaella and Van Reenen, John. “Americans Do IT Better: US Multinationals and the Productivity Miracle”, The American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 1 (2012), pp. 167-201.

Bruno, Randolph; Campos, Nauro and Estrin, Saul. “Gravitating Towards Europe: An Econometric Analysis of the FDI Effects of EU Membership”, Working Paper (2016).

Dhingra, Swati; Huang, Hanwei; Ottaviano, Gianmarco; Pessoa, Joao P.; Sampson, Thomas and Van Reenen, John. “The Costs and Benefits of Leaving the EU: Trade Effects”, CEP LSE Technical Paper (2016a).

Dhingra, Swati; Ottaviano, Gianmarco; Sampson, Thomas; Van Reenen, John. “The impact of Brexit on foreign investment in the UK”, CEP Brexit Analysis 03 (2016b).

Feyrer, James. “Trade and Income-Exploiting Time Series in Geography”, National Bureau of Economic Research (2009).

Harrison, Ann E. and Rodriguez-Clare, Andrés. “Trade, Foreign Investment, and Industrial Policy for Developing Countries”, NBER Working Papers (2009).

Minford, Patrick; Gupta, Sakshi; Le, Vo P.; Mahambare, Vidya and Xu, Yongdeng. Should Britain leave the EU?: an economic analysis of a troubled relationship. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015.

Thompson, Gavin and Harari, Daniel. “The economic impact of EU membership on the UK”, Standard Note: SN/EP/6730 (2013).

Notes:

1- The consensus on modelling Brexit: http://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/consensus-modelling-brexit#.V0wJcqdVKlM.

Scenario #3: A harsh Brexit

Tim Oliver

Introduction

A harsh British exit from the EU is something all involved should wish to avoid. Acrimonious relations between Britain and the remaining EU (rEU) would place an extra burden on European politics, economics, society and security at a time when relations are strained by ongoing crises surrounding the eurozone, Schengen, Russian aggression in Ukraine, the future of transatlantic relations and growing nativist and nationalist tendencies across the EU and Western world. The consequences of a Brexit aligning with these crises should not be overlooked.

To explore how a harsh Brexit would unfold this paper outlines how the foundations for a harsh Brexit already exist in the current strained UK-EU relationship. The paper then considers the consequences – political, economic, social and geopolitical – of any withdrawal deal and post-withdrawal UK-EU relationship that would be part of a harsh Brexit. The paper also briefly considers a positive outcome of a harsh Brexit, albeit one that appears over the longer run.

The paper argues that a breakdown in trust on all sides would be a key factor behind a harsh Brexit and would lead to a UK-EU exit deal and new relationship that are minimal in terms of economic benefits and institutional links. This would fail to provide an adequate framework for UK-EU relations to develop positively. A collapse in trust would be seen in UK-EU relations, Britain’s own internal politics and governance, and between the rEU’s member states.

The problems the rEU would face serve as a reminder that a harsh Brexit would not only be about Britain. A harsh Brexit is likely to emerge should it align with another crisis in the EU such as one within the eurozone or Schengen. Such a development would leave the EU in a position where it can no longer “muddle through” the crises it faces, this being the strategy it has so far adopted with regard to the problems it has faced. The result would be the “European question” in British politics continuing to hinder the British government and the “British question” in the EU triggering larger questions about the nature and unity of the rEU.

The structure of the negotiations

Before we can speculate about a harsh Brexit we need to outline the overlapping negotiations that would handle an exit and how such structures could shape a harsh Brexit scenario (Oliver, 2016a). Britain’s 40-year membership means it already signs up to the EU’s acquis, meaning withdrawal could in some respects be an enlargement in reverse. However, a UK-EU divorce would be a complex one, involving 27 member states, the European Parliament and a host of other interested parties, and it would bring about changes to both UK-EU and internal rEU relations.

The only viable option for managing a withdrawal is that set out in Article 50 TEU. The requirements of Article 50 – in particular the two-year framework to negotiate a withdrawal and the need for the rEU and European Parliament to approve a final deal –give control of the process to the rEU. The requirements of Article 50 have led some British Eurosceptics to argue that triggering the article can be delayed, thus prolonging the negotiating period, or to suggest Britain could repeal the European Communities Act 1972. Both claims have been subject to much critical analysis (Renwick, 2016). If either were pursued they would only contribute to a harsh Brexit by adding confusion, frustration and/or prolonging bitter negotiations.

The identity of who would lead the negotiations on either side would also add to uncertainty and a lack of trust. The rEU side would formally be led by a team from the European Commission reporting to the European Council, although rEU leadership may be limited by the rotating presidencies and the need to account for 27 national views and that of the European Parliament. As we discuss below, the leader of the UK’s negotiating team would be unclear because of the uncertainty hanging over the future of David Cameron.

A British exit would trigger several sets of negotiations. Within Britain there would be negotiations within the governing Conservative Party to handle an outcome many of its senior ministers campaigned against. The British government would have to consult parliament regularly. The slim Conservative majority, divisions within that party and the opportunity for opposition parties to cause trouble means the possibility of a House of Commons vote to reject some part of the UK-EU negotiation would be a very real one. The British government has stated that it has not prepared contingency plans for a withdrawal (Dominiczak and Riley-Smith, 2016), meaning such plans would need to be drawn up quickly. Agreement would need to be reached over the role played by the devolved administrations and regions such as London (D’Arcy, 2016).

On the rEU side several negotiations would overlap. First, rEU-UK: Britain and the rEU would need to reach agreement over the withdrawal terms, the nature of Britain’s future relationship with the rEU and over a series of international trade deals. Britain and the rEU would discuss whatever offer is put on the table, but for the rEU this would only be one side of the negotiation. The EU’s offer would be a compromise worked out between 27 member states – with thought also given to the European Parliament and ECJ – which means EU negotiators would be able to offer few concessions.

rEU(UK): Under article 50 Britain remains an EU member until a withdrawal has been agreed. Until then it can partake in all EU business except that relating to its withdrawal. This means the rEU would have the right to discuss a British exit without Britain’s presence. Britain would make a concerted diplomatic effort to shape the positions of various member states and EU institutions but would ultimately be excluded from key discussions. That said, the possibility for Britain to divide and rule to some extent should not be overlooked. The EU’s complex structures mean it does not always manage a united front when facing partners such as the United States (USA) or competitors such as Russia.

How the rEU – collectively or as individual member states and EU institutions – responds to a Brexit would depend on five Is: Ideas, Interests, Institutions, International and Individuals (Oliver, 2015b). As discussed further below, the biggest tensions within the rEU would be over balancing ideas (e.g. protecting political union) and interests (e.g. limiting the economic costs). Institutional limits such as World Trade Organization (WTO) rules and the EU’s own rules limit what the rEU can and cannot do to punish Britain or offer it in terms of a new relationship. International pressures may convince some rEU member states to seek a quick agreement with a country that still packs a punch internationally. But what would individual leaders such as Merkel or Hollande be able to offer given they face domestic elections in 2017? Some individual leaders would note that their state faces little cost from a Brexit, and so may seek deals on other matters from states that do.

rEU(EU): At the same time, the rEU would be negotiating how to change to reflect the disappearance of Britain. The initial focus would be the allocation of votes under qualified majority voting (QMV), the distribution of MEPs, and changes to the EU’s budget and staffing. We could expect these changes to be fought over because of the wider change to the rEU’s balance of power and direction that a British exit would trigger. These changes would add to the union’s state of flux thanks to the continuing fallout from crises in the eurozone and Schengen. There are numerous potential outcomes for the EU and in a harsh Brexit scenario trust would collapse within the rEU because of arguments over the new distribution of power, perhaps brought to a head in negotiations over a new EU treaty.

rEU-Europe: Negotiations may be necessary if a British exit changed the relationships the rEU has with non-EU European states and with EFTA or the EEA. Should Britain secure a new form of relationship these states may request changes to theirs.

EU business: During the exit negotiations Britain would remain a member of the EU, able to partake in EU business as an ordinary member state. There would be unease within the rEU as to whether Britain should be involved in decisions that shape the rEU’s policies post-UK exit, especially given some British Eurosceptics have argued that Britain could threaten to disrupt EU business as a way of leveraging a good exit deal.

Referendum fallout

The foundations for a harsh Brexit exist thanks to three sets of factors.

First, the UK-EU relationship has long been an awkward one and recent developments provide a context in which a complete collapse in trust is plausible. Britain’s late membership, opt-outs and transactional approach have often set it apart from the rest of the EU (George, 1988). Granted, Britain is not the only awkward member of the EU (Daddow and Oliver, 2016). But Cameron’s approach has worsened the situation thanks to the Conservative Party’s withdrawal from the EPP, UK indifference to the eurozone and Schengen crises, vetoing a new EU treaty, opposition to the appointment of Jean-Claude Juncker as Commission president, invisibility over the situation in Ukraine, a hostile debate about immigration that has strained relations with eastern European countries, and finally the pursuit of a renegotiated relationship using the threat of Brexit as leverage.

Cameron has failed to connect his concerns about the EU with frustration found elsewhere in the EU, instead allowing Britain and the EU to drift further apart. British political debate rarely appreciates how “the British question” has become a concern for the rest of the EU, albeit one that has not been prioritised over others such as the eurozone crisis and which has therefore seemed more of an irritant than a threat to the EU. That means the rest of the EU are to some extent unprepared for a Brexit, and until recently assumed the issue would pass.

Second, Britain’s internal politics and referendum have set the stage for a post-withdrawal UK that would struggle to handle the fallout from a vote to leave. The referendum will fail to address underlying issues behind Britain’s “European question”. The question is not a simple in/out: it is a multifaceted one connected to a wide range of domestic issues, from party politics and political economy through to constitutional and identity issues (Oliver, 2015a). The leave campaigns have offered inflated expectations of what a post-EU Britain would look like and be able to do in areas such as economics or immigration. The referendum has become a battleground for the leadership of the governing party. Cameron has said he intends to stay on as prime minister whatever the outcome, but it seems likely he would be deposed. This sets the stage for a political situation in Britain where the leadership of the governing party is in doubt, heightened expectations amongst Eurosceptics leave little room for the weakened government to pursue a range of options with the EU, and the underlying tensions that fuel Euroscepticism go unaddressed, leaving the EU as the “other” against which a range of political issues are defined.

Third, wider political, economic and social changes across Europe and the Western World would add to a harsh Brexit. The EU has managed to get through the numerous crises that it has faced thanks to a strategy of muddling through, a strategy made possible because the crises have occurred separately. Brexit could align with a Greek exit from the eurozone, migration pressures in Schengen, security challenges in the form of Russian aggression, growing nativist impulses and populism across a number of EU states, and the strained transatlantic relations that see the collapse of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) and a more hawkish US president from January 2017.

Politics

A harsh Brexit would play out politically in three ways.

First, UK politics would be thrown into a period of turmoil as it struggled to handle the outcome of a leave vote. David Cameron could resign immediately or agree to stay on as prime minister until the Conservative Party elects a new leader, which would take three to four months, meaning a new prime minister would be in place by October 2016. This means the government would be in a weakened and perhaps dysfunctional state as it considered how to begin negotiating a British exit. While the main British opposition parties are also in a weaker condition, they would take advantage of any opportunities to deliver blows against the government. We must also take into account a wider sense of strained elite-public relations that would arise from the British people voting against the advice of most of Britain’s political elite and institutions.

Britain’s own internal political tensions would be heightened should the populations of areas such as Scotland or London vote to remain in the EU while large areas of England vote to leave. The SNP government in Scotland would use such a development to call a second independence referendum (Stewart, 2016). The mayor of London could argue that London’s taxpayers (the largest net contributors to the UK treasury) should not have to cover the economic costs faced elsewhere from a Brexit. The potential implications for Northern Ireland’s politics could, in the harshest of scenarios, see the peace process deteriorate (Burke, 2016).

Tensions would also build in UK politics as the heightened expectations amongst leave voters deflate. The government would not be bound by promises made by the leave campaigns. Some voters and campaigners would feel cheated by what follows as Britain struggled to limit free movement, failed to produce the promised billions to spend on the UK instead of the EU budget, to assert British sovereignty, or to secure continued access to the single market. In a harsh Brexit scenario Britain would gain control over immigration, but at the expense of access to the EU single market or any special trade deal, this being the most economically costly option for Britain. Despite this, the influence of the EU’s standards would mean that a large number of EU laws would continue to be felt, causing anger amongst some Eurosceptics, who would argue that the EU continues to infringe Britain’s sovereignty.

Second, the political fallout in the rEU would pave the way for a harsh Brexit because a lack of trust would emerge from the failure to prepare for a Brexit, the difficulties in reaching agreement over what to offer the departing UK, and the fights over how the EU’s balance of power should change as part of a wider crisis facing the EU, such as over a potential Grexit.

As noted earlier, the biggest tension would come down to balancing Ideas and Interests: would the rEU prioritise protecting the ideas of the EU as a political project (thus protecting against the idea of European disintegration catching on), or shared UK-EU security interests and the economic interests of the £61 billion trade deficit Britain runs with the EU (ONS, 2015)? The rEU would have little incentive to offer Britain a more privileged economic relationship than that held by any EU member. Some members, particularly Ireland and the Netherlands, would suffer economically more than others (Irwin, 2015) and so push for a positive economic partnership and potentially veto a deal that does not provide them with adequate compensation. At the same time, decision-makers in both states have been clear they would remain committed to the EU (Möller and Oliver, 2014).

Member states with smaller economic relations with Britain would view the political fallout for the rEU as more important and seek to ensure Britain is in some way punished for withdrawing. The European Parliament, Commission and the ECJ can be expected to prioritise EU unity over relations with Britain. Reaching agreement would be made harder by the rotating EU presidency handling a Brexit: Slovakia (2016), Malta (2017), UK (2017), Estonia (2018), Bulgaria (2018), Austria (2019), and Romania (2019). Britain would give up its presidency. With the remaining presidencies coming from small states, eyes would turn to larger states, and especially Germany, to offer leadership. However, German and French elections in 2017 mean neither Merkel nor Hollande would be able to offer much by way of concessions to Britain or rEU member states seeking concessions. Negotiations would become drawn-out and bitter.

Finally, a failure by the rEU to reach agreement over what to offer Britain would also be the product of manoeuvring by rEU member states to manage the changed balance of power within the rEU. Increased budgetary contributions would be required from a larger number of members, adding to the costs of the EU felt by some states. Attempts to draw up a new treaty and/or handle another crisis in the eurozone, most likely over the exit of Greece, would strain relations to the point of a collapse in trust and equitable burden-sharing between member states.

Economics

In a harsh Brexit scenario the initial economic volatility triggered by a leave vote would be made worse both by the problems in reaching a deal and by an eventual deal offering little to enhance UK-EU economic relations. The end result would be a decline in UK-EU trade, with Britain’s financial services sector being hit hardest, UK FDI declining, TTIP negotiations failing and the EU economy suffering from the costs of reduced trade with the UK as it also struggled with challenges such as another eurozone crisis.

British Eurosceptics often argue that the EU would not hurt itself by punishing Britain economically because of the £61 billion trade deficit Britain runs with the rest of the EU. This is not an opinion felt elsewhere in the EU, where Britain’s decision to leave would be seen as a betrayal. Whatever the political feelings, reaching a UK-EU trade deal would be difficult for both sides because neither has a clear idea of the most adequate post-withdrawal arrangement. As various studies have shown, no alternative relationship would maintain the current economic benefits for both (Booth and Howarth, 2012)

How soon the relationship improved would depend on whether the EU’s own economic situation improved. The eurozone has so far avoided another crisis with Greece, in part out of a desire to avoid this happening before Britain’s referendum. The potential for Brexit negotiations to take several years would increase the possibility of Grexit and Brexit aligning. Fears of contagion from a Grexit have reduced, but the possibility of a controlled and stable exit of Greece from the eurozone remains uncertain.

Brexit would also be likely to complicate and potentially kill the TTIP. The TTIP already faces an uphill battle for approval across the EU. Both the USA and EU have warned that the UK cannot expect to be part of the TTIP if it withdraws from the EU. However, UK non-involvement would make selling the TTIP to the US more difficult given Britain’s significant place in the transatlantic economy.

Social

The most immediate social implications would revolve around the free movement of rEU and UK citizens, their rights in the rEU and UK, and the knock-on effects in terms of careers, families and employers such as social services. A sense of uncertainty already hangs over many EU citizens in Britain. A vote to withdraw would leave EU citizens – denied a vote in the referendum while Commonwealth nationals were granted a vote – feeling like second-class immigrants and potentially unwelcome if a decision to leave was seen to be the result of concerns about immigration.

What happens to the estimated 3 million EU citizens in Britain and estimated 1.2 million British citizens in the rEU would need to be negotiated as part of an exit deal. The House of Lords European Committee (House of Lords, 2016) recently warned of the potential uncertainty that would overhang the “acquired rights” of both sets of citizens. EU citizens in Britain could have their rights slowly worn away, with earning requirements imposed as a condition for continued residence, something recently applied to non-EU immigrants to Britain. A harsh Brexit would likely see little to no agreement, with visa requirements and a breakdown in trust between Britain and eastern European states in particular. There would also be some domestic pressure for Britain’s border to close to EU immigration before Britain had officially withdrawn.

Geopolitics

The geopolitical implications of a harsh Brexit would unfold in three areas: Britain’s unity, the EU’s unity, and EU-NATO/US relations.

A harsh Brexit would see the unravelling of Britain. While the Scottish are not the Europhiles some assume they are, a British exit from the EU would trigger a second independence referendum in Scotland with the economic costs of leaving the UK – the issue Scottish nationalists failed to overcome in the 2014 independence referendum –pushed into second place by political feelings. A Scottish exit from the British single market and an attempt to rejoin the EU would add to the economic uncertainty, political volatility and geopolitical and security risks of a Brexit. A volatile situation in Northern Ireland could also form part of a harsh Brexit, particularly one where the border between Britain and the Irish Republic became more difficult to cross.